Boris Johnson: The inside story of the prime minister's downfall

- Published

Just a week ago, Boris Johnson was insisting he would stay in power. The next day he announced he was quitting, and now the Conservatives are looking to elect a new party leader and prime minister.

So how did everything change so quickly?

Here's the inside story of the prime minister's downfall.

Tuesday 5 July

It was no secret that Mr Johnson was in trouble as he welcomed colleagues to the weekly cabinet meeting.

"We are now able to introduce as of tomorrow the single biggest tax cut in a decade," he told ministers. What he didn't realise was that two of the men at the table - Chancellor Rishi Sunak and Health Secretary Sajid Javid - were thinking about when to quit.

"On that Tuesday morning, I hadn't totally made up my mind, but I was really wrestling with it," Mr Javid says.

"I'd started thinking maybe I'd had enough. In terms of what I could put up [with] and to go and see the prime minister... because I don't think you can work for someone that you haven't got confidence in anymore. It's just a principle value that I have."

Simon Hart, who as Welsh secretary was also in the cabinet meeting, says ministers were aware the situation "was getting more and more challenging and people's patience was being stretched".

"We were in very tricky territory. All knew that there were all sorts of storm clouds gathering and that it was going to be difficult," he adds.

The immediate crisis for the government to deal with was over the behaviour of Conservative MP Chris Pincher. He had resigned as deputy chief whip the previous week, despite denying allegations that he had groped two men at a private members' club.

The big problem for ministers was that there had been other claims about Mr Pincher.

It took the intervention of Lord McDonald, a former permanent secretary at the Foreign Office, to force the government to tell the truth.

Mr Johnson had been told of a similar complaint in 2019, before he had given Mr Pincher a job in his team. But that wasn't the story given by No 10 to ministers to tell the rest of us.

"We get to this week [and] the Pincher episode is growing and growing," says former Brexit Secretary David Davis, who called for Mr Johnson to quit as early as January this year.

"It went from the sort of third item on the news agenda to the top of the agenda, partly because of the way we handled it."

Downing Street's version of events had unravelled and Mr Johnson had to admit it was wrong.

This followed months of criticism of the prime minister's handling of parties that took place in Downing Street during Covid lockdowns. He had himself been fined by police.

Mr Javid says he could sense a growing discontent among colleagues who were being sent out to defend the government on TV and radio. But they had decided to give No 10 "the benefit of the doubt" after being assured there was "not a problem".

"I was sent out to do the media round every so often," says former Justice Minister Victoria Atkins. "You'd go on to talk about something that was really important.

"You were really excited about that, would hope [it] was going to make a real difference, and it got side-tracked into discussions about other things."

Rishi Sunak quit as chancellor and questioned Boris Johnson's competence

But once No 10's untruths about Mr Pincher emerged, it was time for some cabinet ministers to strike.

Mr Javid resigned first, questioning the prime minister's integrity, followed minutes later by Mr Sunak, who said Mr Johnson was not competent or serious.

"I got my resignation letter ready," says Mr Javid. "I signed it, but I wasn't going to tell anyone other than the PM first."

He says he went to see Mr Johnson and explained to him that he would be "resigning now".

"Obviously, he didn't want me to, but he understood."

Were Mr Sunak and Mr Javid's actions co-ordinated?

"I had no idea that he was planning to resign," says Mr Javid. "We hadn't had any, not a single discussion about it whatsoever."

One of Mr Johnson's staunchest allies, Culture Secretary Nadine Dorries, was furious.

"I was quite stunned that there were people who thought that removing the prime minister who's won the biggest majority that we've had since Margaret Thatcher in less than three years [was acceptable]," she says.

"The anti-democratic nature of what they were doing was enough to alarm me. For me it was a coup."

Mr Johnson was in deep trouble.

Wednesday 6 July

By 09:00 there had already been another dozen resignations.

Then Mr Johnson's old frenemy, former Levelling Up Secretary Michael Gove, arrived with a message for the PM that it was all over and that he should quit to spare himself from the spectacle of being dragged down by backbenchers. Mr Johnson told him he would fight, and believed he could stay.

By the time he arrived at the Commons to face Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer for Prime Minister's Questions at midday, four more people had resigned.

Sir Keir Starmer attacked the prime minister amid tumultuous scenes in the Commons

Sir Keir made fun of his rival's predicament, calling the resignations "the first recorded case of the sinking ships fleeing the rat".

Tory MP Tim Loughton asked: "Does the prime minister think there are any circumstances in which he should resign?"

Mr Johnson replied: "The job of a prime minister in difficult circumstances, when he's been handed a colossal mandate, is to keep going, and that's what I'm going to do."

All the while, Labour MPs bellowed and jeered the PM.

"It's hard to describe the feeling of the cauldron and the heat and the mood and the atmosphere," says Simon Hart. "And it was obvious then that we were into some irreversible process."

"It was grim," recalls Ms Dorries. "MPs who were shouting to support the prime minister just the week before were sitting there stony-faced."

Sajid Javid criticised his former boss in the Commons chamber

After Prime Minister's Questions, Mr Javid stood up to make a personal statement over his resignation as health secretary.

"At some point we have to conclude that enough is enough," he told MPs. "I believe that point is now... I have concluded that the problem starts at the top and I believe that that's not going to change."

But Mr Johnson was not for leaving, the memory of his massive 2019 general election win giving him faith that he could survive.

"The fact that he saved us from the constitutional crisis of 2019, took us out of the EU and defeated a very hard-left opposition, those were all great, great things which I celebrate," says Brexiteer Tory MP Steve Baker, "and I would like us to be remembering the best of what Boris Johnson achieved rather than the sordid events of the last week."

Asked whether the PM is a flawed character, he replies: "Everybody's flawed."

Mr Johnson had spent months promising to change as the scandals and missteps, from Partygate to the row over funding of renovations to his Downing Street flat, mounted up.

"This was becoming a little bit too repetitive," says Mr Hart. "Inevitably, there is a point at which people's patience begins to get stretched."

Brexit Opportunities Minister Jacob Rees-Mogg, one of the PM's strongest defenders, admits: "Some mistakes have been made which are the flipside of the prime minister's personality.

"He's a big personality that deals with big issues and, to my mind, he got all the big issues right. On the other hand, he is not necessarily the hottest on the small issues...

"I think the prime minister is a basically truthful man."

'I was never going to desert him'

By-mid afternoon on Wednesday, more ministers were rushing for the door.

"It was plain as a pikestaff that the government was bleeding ministers, almost faster than they could replace them," says David Davis.

By 18:00 BST, 38 members of the government had walked, but Mr Johnson would not budge.

From what increasingly seemed like a bunker, he was claiming there was still a chance he could turn it around.

One of those present tells me No 10 was dangling promotions to try to stave off the onslaught - sketching out a reshuffle on a whiteboard.

There was a feeling staff could could turn things around, that they could "sing Rule, Britannia!, stick their fingers in their ears and it will all be fine", they add.

Mr Hart was among those who told the boss to go.

"It was harder than I thought it would be, and it was sadder than I thought it would be," he says.

"The options were pretty limited by then. And Boris was probably as aware of that as anybody, but, being Boris, I think he always thought 'one more roll of the dice and something miraculous will occur.'"

Watch: Was there a campaign to bring down Boris Johnson?

Ms Dorries continued to defend Mr Johnson.

"I was never going to desert him and I was never going to betray him," she says. "And my advice initially was to fight on."

There were hours of tortured discussion. Mr Johnson was telling colleagues he could and should stay, shored up by a dwindling bunch of colleagues, a source says.

Eventually, even Ms Dorries realised the game was up.

"When the intelligence came in as to who was going to resign the next day and who was going to be handing their letters in, it became apparent we can't withstand this," she says.

"And he made the decision late that night that he would stand down the following morning."

Thursday 7 July

By around 05:00 Mr Johnson admitted to staff it was over.

Just after 09:00 BBC political editor Chris Mason was appearing on a specially-extended edition of BBC Radio 4's Today programme.

"As I speak to you, I'm getting a call from Downing Street," he told presenter Mishal Husain: "The prime minister has agreed to stand down."

It had taken nearly 60 members of the government resigning to make him quit.

A couple of hours later, out came the Downing Street lectern, as Mr Johnson made his formal announcement.

"In the last few days I've tried to persuade my colleagues that it would be eccentric to change governments when we're delivering so much, when we have such a vast mandate and when we're actually only a handful of points behind in the polls," he said.

"But as we've seen, at Westminster the herd instinct is powerful and when the herd moves, it moves, and, my friends in politics, no one is remotely indispensable."

This was vintage Johnson, showing little sign of remorse.

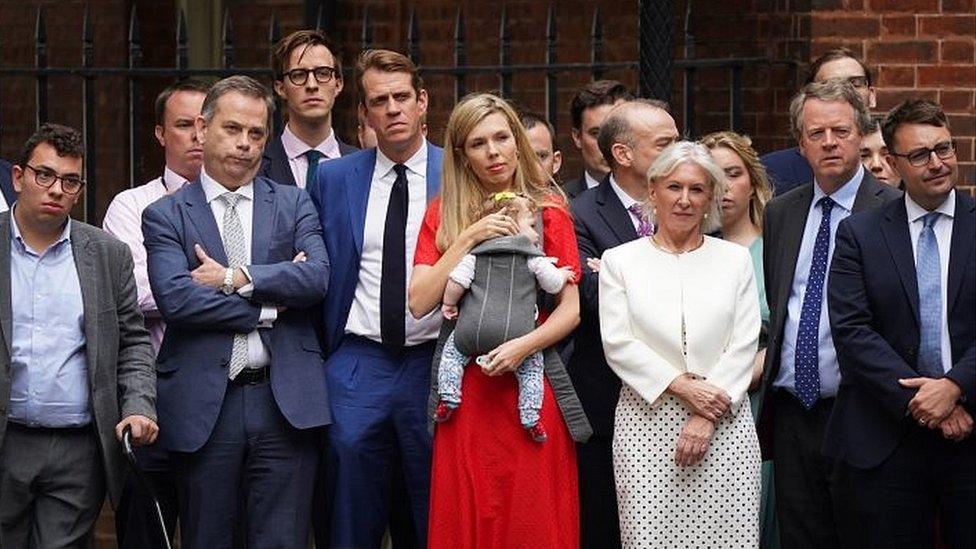

The PM's wife Carrie (centre) was among those watching in Downing Street as her husband gave his resignation speech

In the end, Tory MPs had just had enough.

Mr Johnson's anarchic style, his devil-may-care attitude, had taken him, and them, a long way and given them power and opportunities. But many of them were sick of cleaning up his mess, sick of not being able to trust what was coming out of No 10, sick of Downing Street's attitude to the truth.

Various candidates soon began to announce they would enter the race to replace Mr Johnson.

The search for the next Tory leader and prime minister was already on.

Watch BBC Panorama's The Downfall of Boris Johnson on BBC iPlayer