Bury: The town where football fans are shaping politics

- Published

Could football reform influence how fans vote at the next election?

A year on from a landmark review of English football governance, the future of the game is becoming political. In a Greater Manchester town divided by its football club's demise, fans and politicians tell the BBC where the battle lines are being drawn.

On the kind of dark November night suited to sliding tackles, the squelchy ground beneath our feet is suddenly lit by the glare of lamps.

"We've got the floodlights working again," we're told.

They illuminate the pockmarked turf of Gigg Lane, the home ground of Bury Football Club since 1885.

It was on this pitch that Bury FC won 14 home games in the 2018-19 season, earning them promotion to a higher league.

On the pitch, Bury FC were flying high. Off the pitch, meanwhile, the club was sinking under the weight of its ambitions and how they were bankrolled by owner, Stewart Day.

As Bury FC sat fifth in the league, Mr Day held a meeting with one item on the agenda: the sale of the club for £1. The buyer was Steve Dale, a businessman who promised to clean up the financial "mess" he inherited.

Less than a year later, fans were imploring Mr Dale to sell Bury FC as the club drowned in debt. With no funding to keep the club running, Bury FC was expelled from the football league in 2019 and placed into administration a year later.

Gigg Lane hasn't hosted elite men's football since 2019

"They will not let Bury die," one life-long supporter, Martin Stembridge, remembers thinking. When they did, fans demanded answers.

A review, external found Mr Day spent beyond the club's means and his successor, Mr Dale, "failed to provide adequate proof of funding" to the football authorities before taking over.

When Mr Day stepped down as chairman, he said he had left Bury FC in a stronger position than when he arrived, while Mr Dale has repeatedly argued he did his best to save the club in difficult circumstances.

Mr Stembridge says that had there been robust checks in place, Bury FC's downfall could have been prevented. The problem was, he says, the club had "nobody there - like a regulator - who could step in".

An independent regulator for English football is precisely what many fans have long been clamouring for.

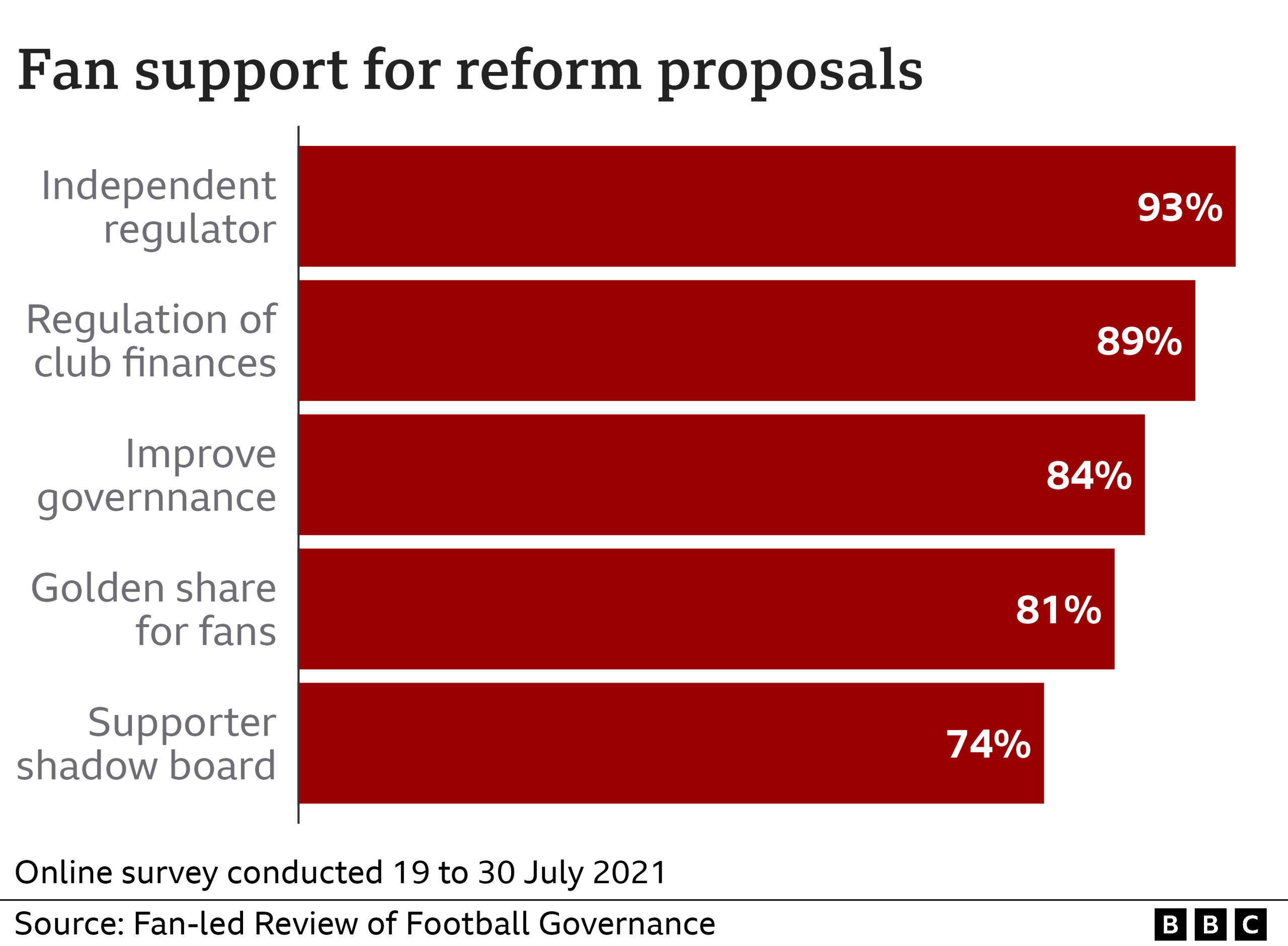

It was the main recommendation of a fan-led review of football governance, external, led by Conservative MP and former sport minister, Tracey Crouch. The collapse of Bury FC was named as one of three catalysts for the review, alongside the Covid-19 pandemic and the ill-fated European Super League.

Released a year ago this week, the review and its 10 strategic recommendations were widely touted as solutions to the beautiful game's ugly problems.

Boris Johnson's government then endorsed all of the proposals and promised legislation to give them legal effect.

Two prime minsters later, the policy document - a white paper - that lays the ground for legislation is yet to materialise. There were fears that former Prime Minister Liz Truss would ditch plans for an independent regulator and go for a more free-market approach.

Then came Rishi Sunak, a Southampton fan who, while campaigning for the Tory leadership in the summer, said he would implement the review in full.

While Mr Sunak has said nothing publicly on the matter since, one government source said "we're not in a Truss world" anymore. Multiple sources in politics and football say the white paper is due before Christmas.

For clubs in financial jeopardy, it can't come soon enough, says football finance expert, Kieran Maguire. Five clubs are on his "watch list" for financial distress and without an independent regulator, football "is likely to see more Burys", he says.

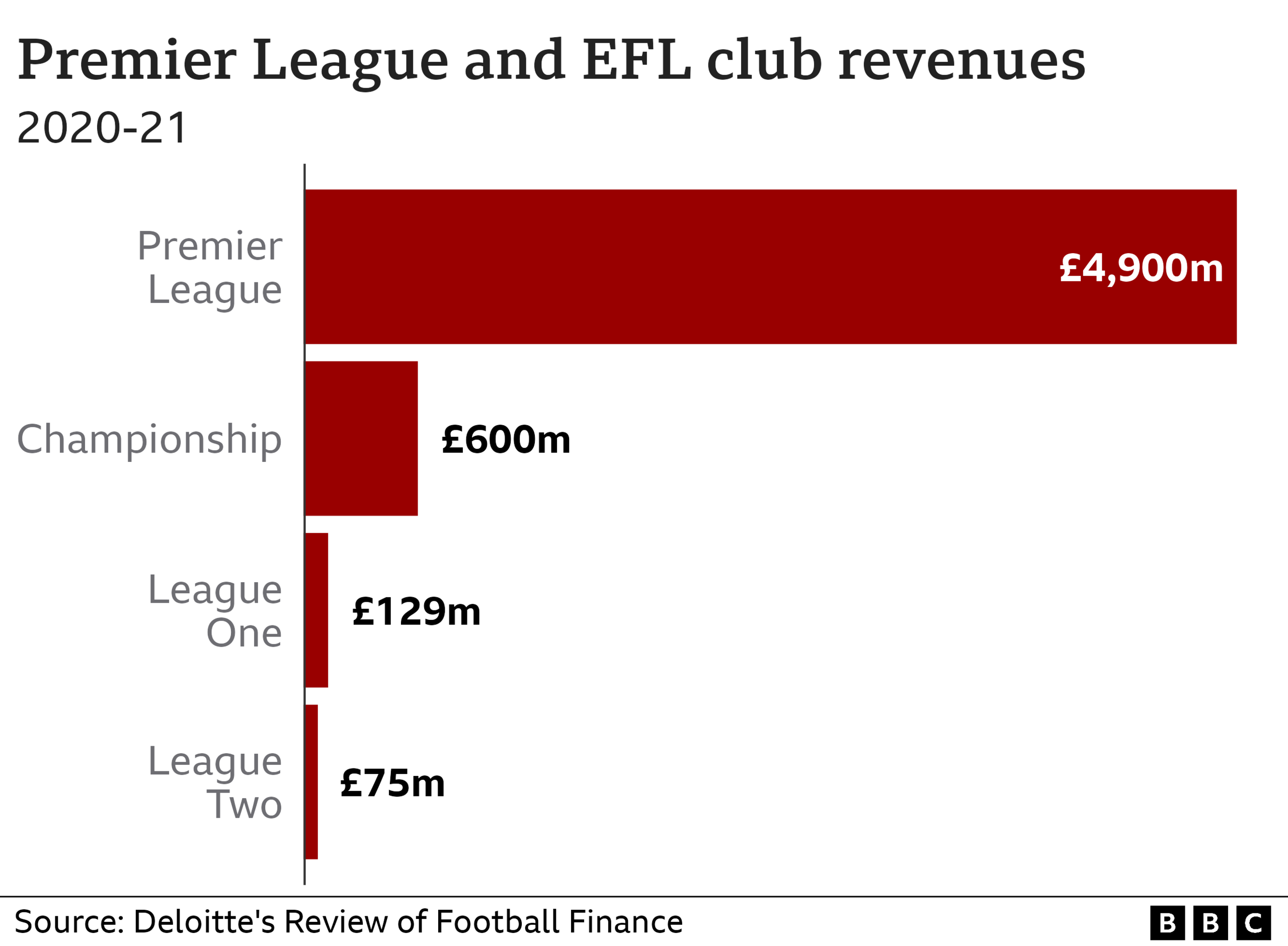

The more the government delays the white paper, the more time lobbyists have to persuade ministers to water down or even scrap some of Ms Crouch's recommendations. The Premier League, in particular, has previously been resistant to the idea of an independent regulator, instead preferring reforms on its own terms.

Mr Maguire, who has been advising the government on financial models for football, says "different parties have been digging their heels in" and "there's an element of uncertainty" under Mr Sunak.

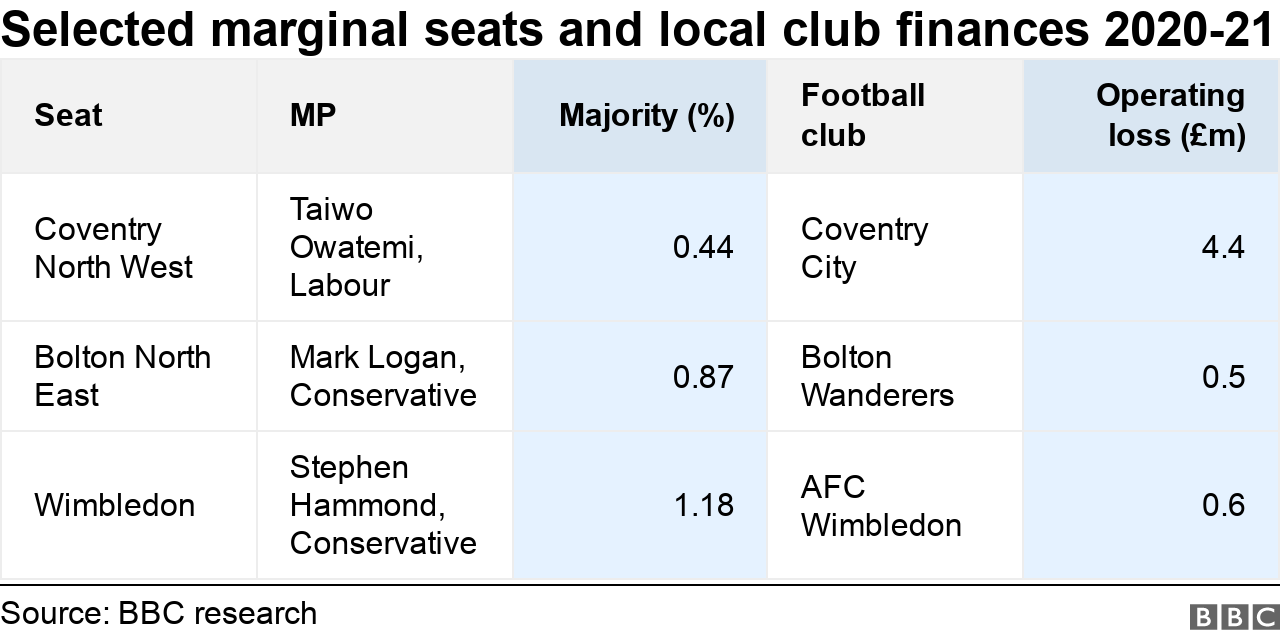

As the footballing community holds its breath, Labour have spotted a chink in the Tory government's political armour.

The party has committed to legislating for an independent regulator, should the Conservatives not do so. If they don't, Labour plans to canvass football fans ahead of the next general election, with a focus on areas where floundering clubs are crying out for reform.

One target is the most marginal seat in England, Bury North, which is held by Tory MP James Daly, who has a majority of 105 votes.

In 2019, those votes earned him a ticket to Westminster, where we meet outside the Parliament in which he's backed calls for an independent regulator of football.

Ministers have reassured him "they're still committed to bringing this in" and he's confident the prime minister won't leave him politically exposed on the issue.

If he does, then Labour and its candidate for Bury North, James Frith, will be ready to pounce.

Bury's political rivals set out their positions on football reform

Mr Frith was the MP for the constituency when Bury FC was expelled from the football league in 2019 and was involved in an abortive attempt to save the club.

Three years on, he's still cheering on a team in the white and navy blue of Bury FC, albeit at a different ground down the road from Gigg Lane. Stainton Park is where Bury AFC is playing Irlam tonight and all its matches this season in the ninth tier of English football.

The fan-owned 'phoenix club', which raised from the ashes of Bury FC in 2019, restored "a sense of hope", Mr Frith says. To protect this club and others, he says, "the government should come good on what it said" about the independent regulator.

It's something Mr Frith will be campaigning for, alongside fans like Phil Young, chairman of Bury AFC's fan group, the Shakers Community.

If an independent regulator doesn't happen, Mr Young says, football fans will be questioning "whether this is just another false promise" made by the Conservatives.

Those fans once numbered 4,000 at Gigg Lane - almost 40 times more than Mr Daly's majority.

He helped another fan group, the Bury Football Club Supporters Society (BFCSS), secure £1m in government funding to buy Gigg Lane last year. The levelling-up grant was used to revive the stadium as a community asset and acquire the rights to Bury FC's name.

"From that point of view, if you're a Bury supporter, you would vote Conservative," says Daniel Bowerbank, chairman of BFCSS.

Bury supporters groups on the political impact of football reform

The government money has only got Mr Bowerbank's group so far, though.

Under a deal to bring elite men's football back to Gigg Lane, the Labour-controlled Bury Council has committed £450,000 in funding if fans agree to form a single supporters' society.

A merger of the two fan groups came tantalisingly close this month, only to be narrowly rejected in a vote.

There's distrust and personal animus on both sides, with disagreements on how a resurrected Bury FC should be run and whether returning to Gigg Lane is viable.

The split typifies the tribalism of both football and politics, pitting two groups with diverging values against each other, one seemingly leaning towards Labour, and the other Conservative.

Bury North's MP - and its previous one - say they are not taking sides and both champion a merger in some form.

"No-one is looking to use this as a political football," Mr Frith says at Stainton Park, where his presence may give some fans reason to believe otherwise.

Unlike the result of the match he's watching - which finishes 1-1 - there can only be one winner in Bury North after the next general election.

Additional reporting and video production by Morgan Spence

Related topics

- Attribution

- Published27 September 2022

- Attribution

- Published1 November 2022

- Attribution

- Published25 November 2021