'I'm living in fear for my life in Afghanistan'

- Published

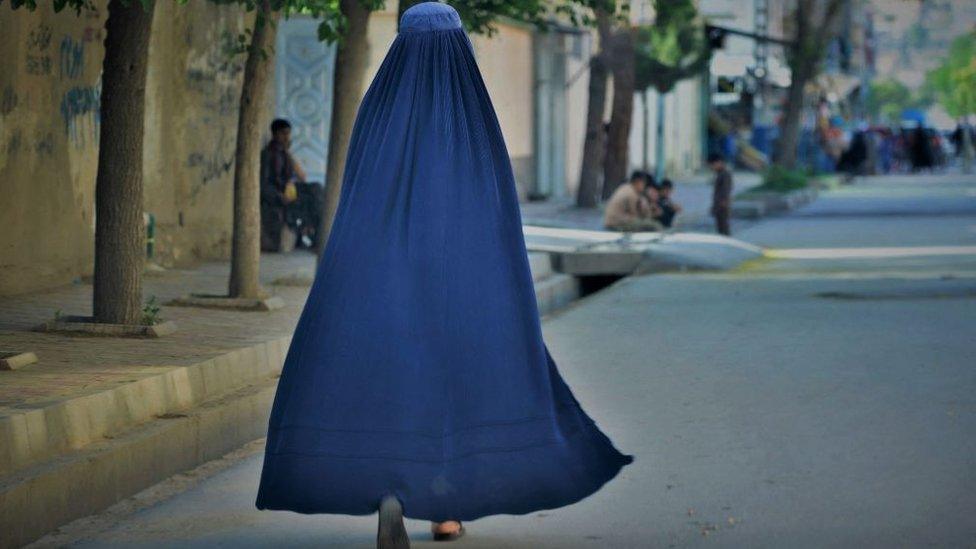

Women's rights in Afghanistan have been curtailed since the Taliban takeover (file picture)

It is nearly 11 months since the UK launched its scheme to help vulnerable Afghans come to the UK. But MPs and charities say the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS) has been too slow to get up and running and is leaving those who are in most danger stuck in Afghanistan.

"Every minute, every moment is frightening. We are scared for our own safety," says Ghazal.

Because of her previous job as a journalist and lecturer, as well as being an advocate for women's rights, Ghazal says she has been threatened by the Taliban.

The BBC is not using her real name as she fears reprisals from the hardline Islamist group, which seized power in the summer of 2021.

She applied to come to the UK through the ACRS in June and received a reference number but has heard nothing else since then.

As she is still in Afghanistan she is not eligible for the first year of the scheme, when only three specific at-risk groups who remain in the country are being considered.

Meanwhile, Ghazal is moving between the houses of friends and relatives with her sister so she cannot be found.

Since the Taliban takeover, women's rights have been curtailed, with women barred from most jobs outside the home, secondary education and travelling longer distances without a male guardian.

Ghazal is unmarried and as she is unable to do her old job she is struggling financially, with her savings now gone.

"I had a huge reputation, a successful career and respect. Financially, I was well off. I had my dream job... but all of a sudden jumping down from there to someone who doesn't even have an identity is very painful and stressful," she tells the BBC, speaking through a translator.

Asked what she thought would happen to her and her sister if they stayed in Afghanistan, Ghazal says: "Probably we will end our life, someone will kill us, or we will have a heart attack."

"We have no hope for our future," she adds.

Labour's shadow immigration minister Stephen Kinnock says the government promised to prioritise groups who stood up for democracy, including women's rights activists and LGBT campaigners.

But in the first year of the ACRS, most vulnerable groups must already have left Afghanistan to be considered for the scheme.

Crossing the border to neighbouring countries can be dangerous as it difficult to obtain travel documents, particularly for those who are in hiding.

Mr Kinnock says all at-risk groups in Afghanistan should be eligible for resettlement in the first year and helped to leave the country.

"It really is shameful that we have failed to live up to our obligations and to support those people," he tells the BBC.

"They stood up for the values that we cherish - democracy, inclusion, rule of law - and as a result, they put their lives on the line. In many cases, we've abandoned them."

Thousands of people were evacuated from Afghanistan to the UK in August 2021

Most of the Afghans who have come to the UK were evacuated as part of Operation Pitting, which saw around 15,000 people airlifted out of Kabul as it fell to the Taliban in August 2021.

Most of these were British nationals, as well as people who worked with the UK in Afghanistan and their family members, who are eligible under the Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy.

After its withdrawal from Afghanistan, the UK pledged to resettle up to 20,000 more vulnerable Afghans in the coming years under the ACRS.

The ACRS has three pathways for resettlement, external:

Under pathway one, the first to be accepted under the ACRS were individuals who had already arrived in the UK as part of the original evacuation last year. Others who were authorised for evacuation and subsequently managed to get to the UK are also eligible under this pathway

Under pathway two, the UK is taking referrals from the UN refugee agency, the UNHCR, of vulnerable people who have managed to flee Afghanistan for neighbouring countries

Under pathway three, only three groups are being considered in the first year - British Council contractors, contractors for GardaWorld, which provided security at the British Embassy in Kabul, and alumni of the UK's Chevening university scholarship scheme

After the first year, wider groups of vulnerable people in Afghanistan will be considered under pathway three, including women, religious minorities and others at risk of persecution

The scheme formally launched in January but pathways two and three only opened in June.

The UNHCR has referred 801 Afghan refugees to the UK this year up to the end of October but only 67 have departed for resettlement, according to the latest figures, external.

Only four individuals had been resettled in the UK under pathway two up to the end of September, according to Home Office figures, external.

Mr Kinnock says processing of cases needs to be sped up so people are not left "languishing" in refugee camps, "terrified" they could be sent back to Afghanistan.

There are 1,500 places available under pathway three in the first year but the Home Office would not confirm whether people had started to arrive in the UK under this pathway yet.

The rest of the roughly 6,300 Afghans granted indefinite leave to remain under the ACRS were through pathway one.

A Home Office spokeswoman says this includes "people who stood up for values like democracy and freedom of speech", as well as vulnerable groups, including women and girls.

Protesters took part in a march in London on Sunday calling for more support for Afghan women

Earlier this month, a cross-party group of eight MPs and peers wrote to the foreign secretary calling for a specific asylum route for Afghan women who are at risk.

One signatory, former Conservative minister Caroline Nokes, says it has been "next to impossible for Afghan female activists to find a safe route to the UK" and "we're letting them down".

Tamsin Baxter, from the Refugee Council charity, says the ACRS does not put those "most in danger at its heart".

"We're talking about people whose lives are clearly at stake," she says.

She says progress on resettlement has "stalled significantly" since the initial evacuation last year.

"Many people face a dreadful wait of two, even three years before they might find safety here. The fact is that these people are desperately unsafe and simply can't wait that long."

- Published5 August 2022

- Published25 July 2022

- Published6 January 2022