Matt Hancock and Isabel Oakeshott: A tale of scoops, betrayal and WhatsApp

- Published

Watch: Matt Hancock WhatsApp message row in 83 seconds

He says it was a "breach of trust". She insists it was in the public interest. What does the row between Matt Hancock and the reporter who leaked his WhatsApp messages reveal about how journalism works?

It's a brilliant scoop.

And, in the world of journalism and beyond, scoops are the stories you remember.

They can bring down Presidents (think Watergate), force MPs from office (think the MPs' expenses scandal) and they can even shine a spotlight on the worst excesses of the media (think phone hacking).

The Telegraph's Lockdown Files are an insight into decision-making at the heart of government during the most testing and turbulent time in recent British history.

But behind them is a fascinating story of betrayal and journalistic ethics.

On one side is Isabel Oakeshott.

A political journalist with a proven track record of breaking stories, she is also an anti-lockdown campaigner and the partner of the man who leads Reform UK - the reincarnation of the Brexit Party, which aims to take seats from the Conservatives at the next election.

She's no stranger to controversy.

Her previous journalism led to the jailing of both Chris Huhne, a former cabinet minister who broke speeding laws, and the source of the story, his ex-wife Vicky Pryce, who took his points.

Ms Oakeshott also co-authored a book in 2015 about then-Prime Minister David Cameron. Famously, Call Me Dave included an unsubstantiated allegation about a sex act on a dead pig's head.

Watch: Isabel Oakeshott reveals why she leaked the messages

On the other side is Matt Hancock. Health secretary throughout the pandemic, Mr Hancock had to resign after breaking his government's own lockdown rules, and, while still an MP, has been trying to rebrand himself on reality TV, most notably with a successfully protracted appearance on I'm A Celebrity Get Me Out Of Here.

Giving Ms Oakeshott the means, potentially at least, to damage that brand can't have been part of his plan. But that is exactly what he has unwittingly done.

Landing the story

Her scoop for the Telegraph is journalistically unusual. Often these stories are delivered by leaks from brave and trusted sources, who sometimes put their jobs on the line in the name of the public interest or to expose wrongdoing.

We don't know, for example, who leaked the details to ITV of the revelations about lockdown parties in Downing Street during the pandemic. Perhaps we never will.

The Telegraph's Covid splash is very different because Matt Hancock is the source. His ghostwriter really has come back to haunt him.

When the pair decided to collaborate on his Pandemic Diaries, Mr Hancock's diary-style account of his experience of government during Covid, Ms Oakeshott signed a confidentiality agreement.

He handed over more than 100,000 WhatsApp messages between himself, other ministers, aides and public health advisors.

These are the messages she has now given to the Telegraph. We are promised perhaps a week of revelations. Questions are being asked about Matt Hancock's judgment in trusting Isabel Oakeshott at all.

Words matter

In a sense this story is about words - 2.3m of them, delivered in the WhatsApps, and the ensuing war of words between Ms Oakeshott and Mr Hancock.

Each has a very different interpretation of events.

She says, backed by the Telegraph, that her decision to publish the messages is in the public interest. "No journalist worth their salt," she told Radio 4's Today programme, "would sit on a cache of information on such a historic matter and cover that up."

Mr Hancock issued a statement saying there is "absolutely no public interest case for this huge breach" because he has already given them to the UK's independent public inquiry into the pandemic.

He says releasing the messages was a "massive betrayal and breach of trust".

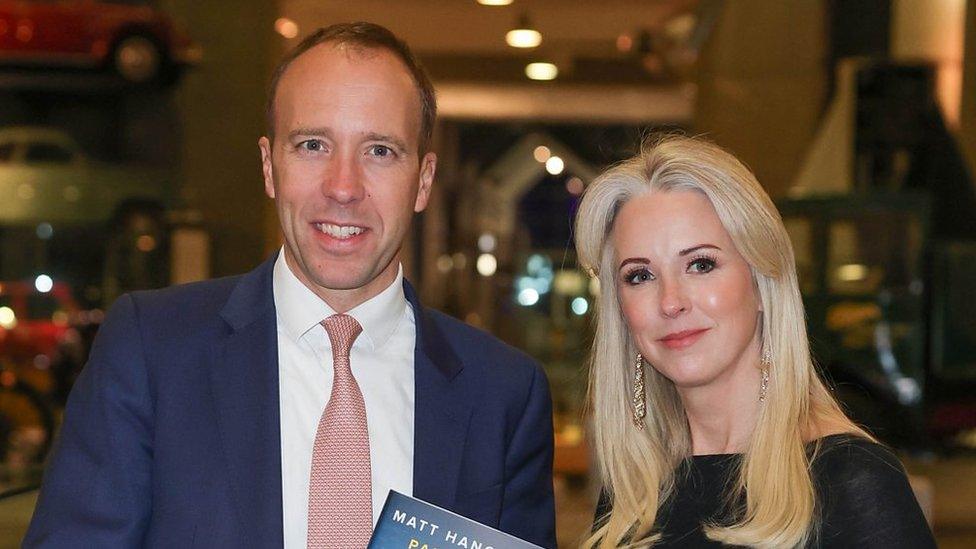

Matt Hancock collaborated with journalist Isabel Oakeshott on his book Pandemic Diaries

Ms Oakeshott put out a statement today saying she makes "no apology for acting in the national interest: the worst betrayal of all would be to cover up these truths".

She added "the greatest betrayal" was to the entire country and to children in particular, who "paid a terrible price" as a result of "the response to the pandemic and repeated unnecessary lockdowns".

Mr Hancock has termed the Telegraph stories a "partial, biased account to suit an anti-lockdown agenda".

A spokesperson added: "It is outrageous that this distorted account of the pandemic is being pushed with partial leaks, spun to fit an anti-lockdown agenda, which would have cost hundreds of thousands of lives if followed."

Ms Oakeshott told Piers Morgan on Talk TV, where she is also international editor, that Mr Hancock reneged on an undertaking to do an interview with the channel after the book was published. "It's not of course the reason I did this," she added. Others may wonder whether they cross her at their peril.

In another example of two opposing narratives, Ms Oakeshott says she was not paid to write the book.

An ally of Mr Hancock told me: "It's incredibly disingenuous and misleading to say she hasn't been paid for the book. She has and will also receive royalties."

Those royalties might not be very large if reports that the book sold just 3,304 copies in its first week and 600 in the second are correct. Publisher Biteback declined to comment when approached by the BBC.

Telling stories

So what does the saga tell us about how the media operates?

Journalism often works on trust. Clearly that's broken down in this case, although people are asking why, even with a confidentiality agreement, Mr Hancock felt he could trust Ms Oakeshott.

The Telegraph, presented with the cache of messages, decided, as its Associate Editor Camilla Tominey put it, that "the public has a right to know as much as possible". The decisions made during the pandemic were a "matter of life or death".

They will have taken advice that the confidentiality agreement can be broken in the public interest - and that Mr Hancock is unlikely to sue. He is understood to be examining all options open to him.

If it is correct that he wasn't notified before publication, that would be an interesting insight into the workings of journalism. It is customary to offer people a right of reply, often with some time built in ahead of publication.

However, that window can be squeezed on a breaking story, or if it is decided that offering a longer time frame might give the subject time to block publication.

In the end though, the background to the Lockdown Files may tell us more about how Isabel Oakeshott operates than about the media more widely.

She has become the story, at least in part, touring the TV and radio studios and sparking debate about how it came about.

Sir Craig Oliver, who served as director of politics and communications for David Cameron, told me that "the danger for Isabel Oakeshott is that she ends up caught up in a row about journalistic ethics which overshadows what she is trying to achieve".

He added: "She wanted to bring forward the lessons of the public inquiry, to highlight decisions made about lockdown and the experiences of children in school, for example. She probably didn't intend the debate also to also focus on the ethics of journalism."

For some, she's delivered an important scoop and the way she got the story is entirely justified. Others feel differently.

One thing is certain: the roll-out of stories goes on.

Related topics

- Published1 March 2023

- Published21 September 2015

- Published11 March 2013

- Published2 March 2023

- Published1 March 2023