Jeremy Hunt: More immigration not a Brexit betrayal

- Published

Job vacancies in the construction industry have been on the rise in the UK

Jeremy Hunt has denied that the decision to give some overseas construction workers easier access to UK jobs was a "betrayal of Brexit".

The chancellor's budget relaxed immigration rules to help construction employers fill certain vacant roles.

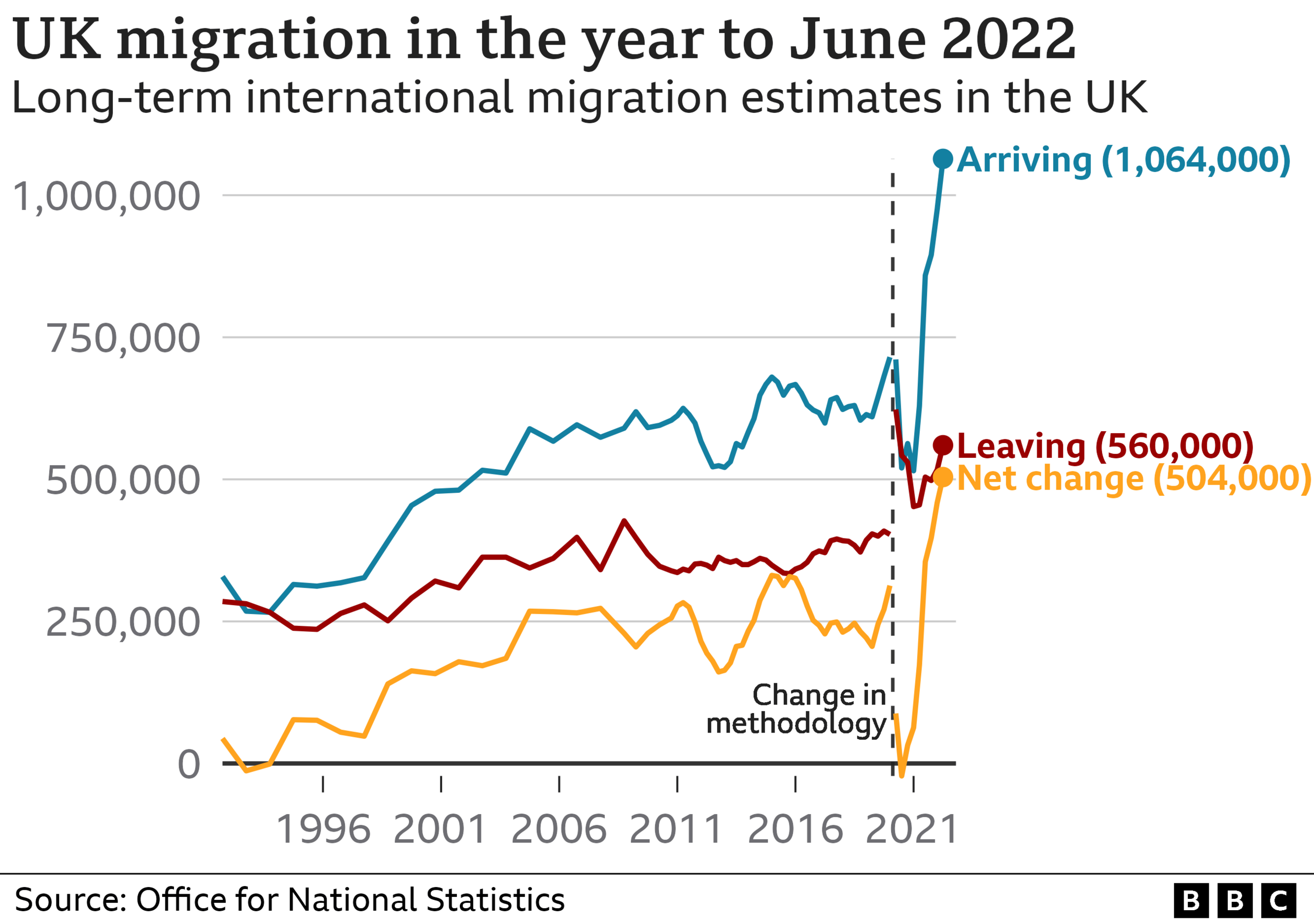

Net migration to the UK - a prominent political issue ahead of the 2016 EU referendum - rose to a record high of about 500,000 in 2022.

But Mr Hunt said "people who voted for Brexit didn't vote for no immigration".

He told the BBC they voted "for control of migration" and argued the back-to-work policies announced in his budget on Wednesday were "an important part of delivering our Brexit promise".

He said he had accepted the recommendations of the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC), which advises the government on how many foreign workers should be granted visas.

The committee recommended that five jobs - including bricklayers, roofers and plasterers - should be added to the government's shortage occupation list, which helps employers fill certain roles.

People in professions on the shortage occupation list are able to apply for a skilled worker visa and take up jobs in the UK.

A review of worker shortages in hospitality and construction, external revealed that vacancies have risen sharply in both industries, relative to pre-pandemic levels.

In a BBC interview, Mr Hunt was asked if the change on construction workers was "a betrayal of Brexit" for British people who voted to leave the EU "on the grounds that the jobs would go to them and their children".

"No," he replied.

"What those people who voted for Brexit want is an economy, an economic model, that does not depend on unlimited, low-skilled migration," Mr Hunt, who campaigned to remain in the EU, said.

"What those people want is to know the government has a plan to remove the barriers to stop people working in the UK, to make sure we invest in our skills. That was the plan that I announced yesterday."

The Labour Party has accepted the need for skilled foreign workers, but has promised a plan to train British workers to fill job vacancies.

Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves told the BBC that bringing in migrant workers would not be Labour's priority to address skills shortages.

"We would rather there was more support given to train up people who are already in Britain," she said, adding that one way Labour would do this would be by reforming the apprenticeship levy to help young people get into jobs.

'Surprise' migration levels

The freedom of EU citizens to live and work in the UK - and British citizens to do likewise in any EU country - without needing a visa ended in 2021 following the Brexit vote.

Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer has ruled out restoring freedom of movement and says the UK must wean itself off "immigration dependency".

However, the CBI - the UK's biggest business group - says immigration is needed to solve worker shortages and boost economic growth.

Some Brexit supporters say leaving the EU has given the UK more control over migration policy.

A post-Brexit points-based immigration system - which covers EU and non-EU migrants - was launched by the government at the end of 2020.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported that net migration - the difference between people arriving and leaving - stood at just over 500,000 in the year ending June 2022.

This represents a record high and an increase of 331,000 on the previous year, ending June 2021.

The ONS said the rise was driven by non-EU migrants, specifically students, and the resumption of post-pandemic travel. It also said the war in Ukraine, the resettlement of Afghans and the new visa route for Hong Kong British nationals had all contributed.

The Office for Budget Responsibility has predicted a decline in net migration, with the number expected to settle at 245,000 a year from 2026 onwards.

The chairman of the OBR, Richard Hughes, said he had been "consistently surprised by the level of net migration under the new post-Brexit migration regime".

He said "significantly more" migrants have arrived in the UK than the OBR expected.

The rise of legal migration to the UK was one of the most hotly debated political topics in the build-up to the EU referendum in 2016. The Leave campaign said Brexit would allow the UK to "take back control" of immigration policy.

Former Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron once promised to get immigration down to the tens of thousands a year. But net migration has been over 200,000 and rising since the late 1990s.

In October 2022, Home Secretary Suella Braverman said her "ultimate aspiration" was to reduce net migration to the UK to the "tens of thousands".

Related topics

- Published16 March 2023

- Published22 November 2022