Laura Kuenssberg: Can we avoid a summer of strikes?

- Published

"There is no sense of an actual strategy", complains one union leader, fresh from talks with government ministers.

Whether you're waiting for a hip operation, a new passport, wondering what you're going to do with your kids when their teachers leave the classroom for the picket line, or are a university lecturer worried about losing pay when you protest, walkouts aren't anywhere close to coming to an end.

Whoever you blame, a winter of widespread industrial discontent might be followed by a summer of strikes under Rishi Sunak, and it's simply not clear how the government intends to deal with it.

Take nurses first.

Their strike action earlier in the year was unprecedented. A bitter back and forth with ministers was eventually to be resolved with an offer of a 5% pay rise and a one-off payment of at least £1,655.

The nurses union leader, Pat Cullen, who'll be with us in the studio on Sunday, told her members it was worth accepting.

But they said no.

So the strikes are back on, and will be more significant, with staff being withdrawn from emergency departments for the first time.

And there's to be another ballot, with members being asked to approve possible strikes up until December.

It's messy for the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) though, not just because Unison, a bigger health union, has accepted the deal, but also because the RCN leadership urged its rank and file membership to approve the pay proposal.

Behind the scenes, there has been an active campaign to reject the terms of the suggested agreement.

Pat Cullen meets RCN members on the picket line

One of the campaigners involved told me there were as many as 100,000 health workers on a closed social media group who had discussed whether to accept or not. Thousands took part in open zoom meetings, thousands of leaflets were distributed, with campaigners working hard to "vote reject".

They said during the bitter winter protests, "when we heard Pat Cullen in minus 5 degrees, she stood beside us and said 10% was a red line - anything less than that is a real terms cut".

There's a feeling that taking the step to go on strike in the first place - something the RCN has not done before in its 106-year history - has increased their determination, they said, adding: "A lot of RCN members have been radicalized and politicised around the struggle."

The RCN leadership might even be starting to think it has lost control, perhaps fearing "we've fired these people up and now we don't know what to do", the campaigners suggested.

The ongoing spat between the government and junior doctors has not helped the atmosphere either.

Union sources say they weren't surprised by the result of the latest strike ballot, although they had recommended their members back the deal, such was the strength of feeling not just about pay, but about the challenges the health service faces.

This week, Laura hears from Greg Hands for the Conservatives, Wes Streeting for Labour and Pat Cullen, general secretary of the Royal College of Nursing

Carole Mundell, director of science at the European Space Agency will also join her

Watch live on BBC One and iPlayer from 09:00 GMT on Sunday

Follow latest updates in text and video on the BBC News website from 08:00

The nurses' rejection of the deal is of course a huge problem for the government too.

Months into multiple disputes, their handling of industrial action has been called into question, and their approach has, diplomatically put, evolved.

Ministers have offered a changing set of explanations and pleas to nurses and other workers not to go on strike.

Rishi Sunak and Steve Barclay face growing pressure to find a solution

They said a pay rise for all public sector workers would cost every household £1,000. Our number crunchers at the BBC, and the independent IFS, showed why that was not quite the case, as you can read about here.

In December, foreign secretary James Cleverly tried to suggest that doing a deal was not really up to government, and was a matter entirely for the NHS and the unions, after the recommendations from the independent pay body.

Again that's not really the case.

Health secretary Steve Barclay was of course, deeply involved, as were the Treasury, and Number 10.

Ministers also repeatedly said that it was impossible to talk about pay for this year.

But in the end, the offer they put on the table did include a one-off payment, in a sense to cover the union's demand to look at pay for 2022 and 2023, so that changed too.

The government also attempted to apply pressure on the unions by trying to change the law to make it harder to strike. This didn't shift the dial.

Perhaps the most eyebrow-raising reason given by the government for not budging came from then-cabinet minister Nadhim Zahawi, who suggested in December, external that nurses would be helping out Vladimir Putin if they took industrial action.

In the end, however, ministers worked out a deal with the RCN they hoped would be seen as a benchmark for other industrial disputes.

Ironically, it's the RCN deal that has fallen at this important hurdle, souring the mood.

The leader of one of the other big unions suggests the government "thought boxing off the RCN was a clever move, but it's just not the way unions work …they were more focused on the PR than industrial relations".

So far, there has been no significant contact between the government and the RCN since Friday's announcement of further strikes.

The health secretary is yet to reply to the RCN's letter asking for urgent talks.

A few informal suggestions have been made, about the possibility of what's been described as a few "sweeteners", even an idea of helping nurses with their parking costs.

The notion, at this stage, that a few tweaks here and there will solve the dispute seems far fetched.

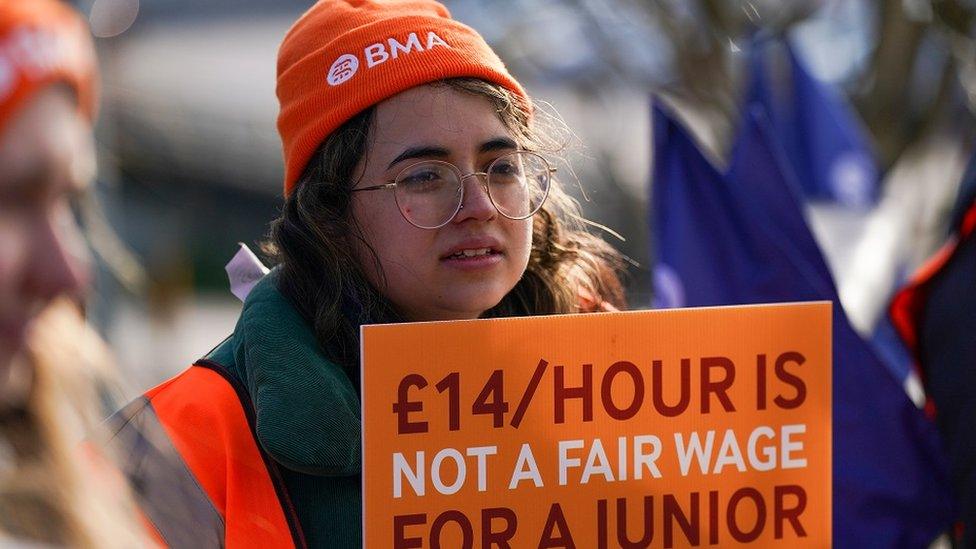

Junior doctors are set for further industrial action

Downing Street is reluctant to say much about what is going on with the RCN until all the health unions have had their say on the deal. That is not for another couple of weeks.

A government source said ministers' "general stance had been a sober reflection of what's affordable", and that broadly they believe they are "getting the right balance", with inflation eating away at everybody's wages.

But the fight with the RCN, which ministers hoped had been resolved, makes the atmosphere between the government and unions even more fraught.

There is little sign of a deal with the teaching unions, set to strike soon. There's the ongoing dispute with junior doctors, who could end up on strike at the same time as nurses in England.

Civil servants are likely to walk out too, having missed out on a one off payment for 2022/3, which other workers had been granted.

Dave Penman, leader of the FDA civil service union, warns the consequence will be a "prolonged and damaging dispute".

Another union leader told me the government has to confront a "sense of burning anger" among public sector workers if they want to bring this series of disputes to an end.

The public disruption of course has a political cost too. Not just because of the inconvenience and risks from the action itself, most profound in the health service, but the wider consequences for Rishi Sunak.

Remember, he has asked you to judge him on five specific promises - one of them to bring NHS waiting lists down, which hospital bosses warn is impossible for as long as industrial action is taking place.

Another is to get the economy growing which, the Office for National Statistics said this week, was not happening, partly because of strikes taking place.

Allowing industrial action to continue makes it harder for the prime minister to achieve his targets, dampening Conservative hopes of some kind of political recovery.

Rishi Sunak's supporters have pointed gleefully to an apparent tightening of the opinion polls, external in recent weeks, a dire situation looking, by some measures, slightly less bad.

The approaching local elections, which used to be pointed to as some kind of potential moment of Armageddon for his leadership, now seem less of a moment of jeopardy.

But rolling industrial action which will hit real lives presents serious political risks for the PM.

And right now there seems no easy solution to what could be a summer of strikes.

Follow Laura on Twitter, external