Chief whip issues warning to Tory MPs who rebelled on Rwanda

- Published

- comments

Former Home Secretary Suella Braverman and former immigration minister Robert Jenrick were among the 11 Tory MPs to vote against the government

The 11 Conservative MPs who defied the prime minister over his Rwanda migrant plan last week are being called in by the government to explain themselves.

The Tory backbenchers, including the former Home Secretary Suella Braverman and the former immigration minister Robert Jenrick, are expected to meet the government's Chief Whip Simon Hart later.

Mr Hart, whose job it is to ensure the government wins votes in the House of Commons, will meet the MPs one-on-one, having been asked to do so by the prime minister.

Senior government figures say the meetings, which are often standard practice after a high-profile rebellion, are "about sending a message that rebelling is not going to be tolerated going forward".

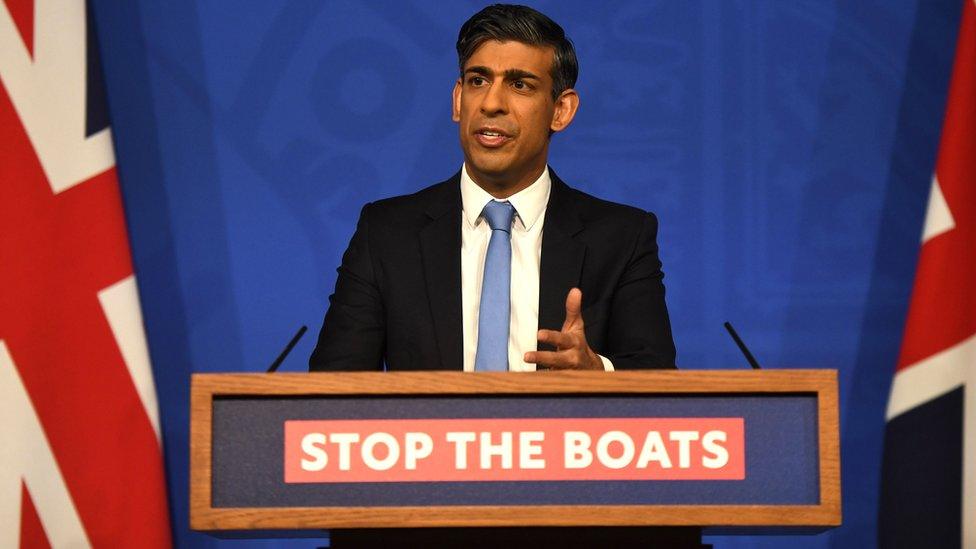

They are also about the government attempting to illustrate its power, after a week in which the power, authority and judgement of Rishi Sunak was repeatedly and noisily questioned by plenty on his own side.

The threat, that rebelling is "not going to be tolerated", is vague and meant to be so. It can be read as a final warning, that behaving in a similar way again might lead MPs to be thrown out of the parliamentary party.

But it doesn't commit No 10 to doing this.

Some of the rebels, for their part, reckon Mr Sunak is too weak to do this and doing so would provoke further turbulence in the party, the very thing he is desperate to avoid.

The government's Rwanda policy will be debated in the House of Lords later.

Peers will look at a report published last week, external by the International Agreements Committee, which implies a further delay to the policy necessary.

The committee is chaired by the former Labour Attorney General Lord Goldsmith.

Boris Johnson's former chief of staff in Downing Street, the Conservative peer Lord Udny-Lister, is also on the committee.

And here is the committee's key conclusion: "The government has presented the Rwanda Treaty to Parliament as an answer to the Supreme Court judgment and has asked Parliament, on the basis of the treaty, to declare that Rwanda is a safe country.

"While the treaty might in time provide the basis for such an assessment if it is rigorously implemented, as things stand the arrangements it provides for are incomplete. A significant number of further legal and practical steps are required under the treaty which will take time."

We haven't heard the last of the debates about sending some asylum seekers to Rwanda.

And we haven't heard the last of those at Westminster who aren't convinced the government's plans can, or should, work.

Related topics

- Published18 January 2024

- Published13 June 2024

- Published20 January 2024