Draft EU deal: What Cameron wanted and what he got

- Published

David Cameron has hailed a draft EU reform deal as delivering the "substantial changes" he wants to see to the UK's relationship with the 28-nation bloc.

He says some work is needed to hammer out the details ahead of a crunch summit in Brussels on 18 February.

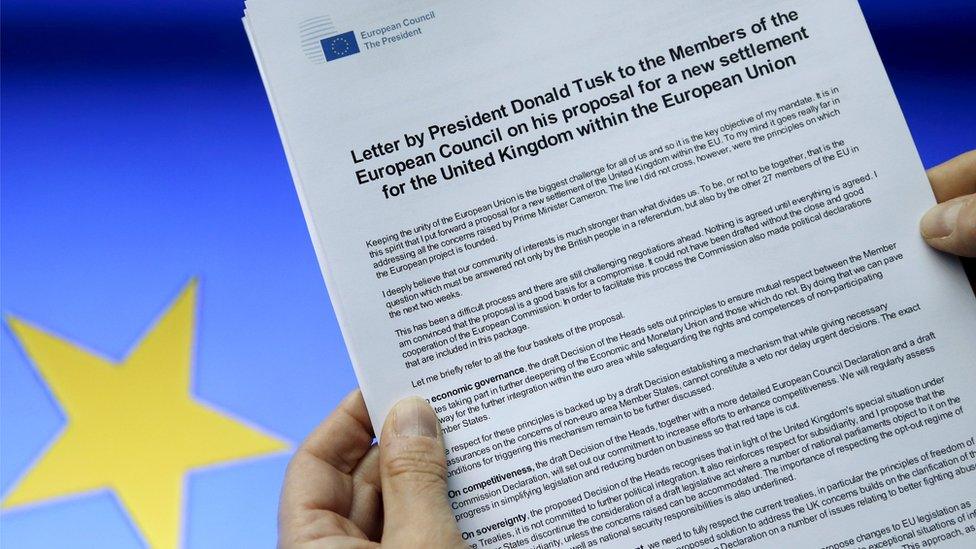

But how does the 16-page letter drawn up by the President of the European Council, Donald Tusk, external, measure up to what the prime minister originally wanted from the negotiations?

The BBC's chief correspondent Gavin Hewitt gives his verdict while Europe correspondent Chris Morris looks at how the deal will be perceived elsewhere in the EU.

Mr Cameron says the draft deal delivers "substantial change"

Sovereignty

What Cameron wanted: Allowing Britain to opt out from the EU's founding ambition to forge an "ever closer union" of the peoples of Europe so it will not be drawn into further political integration in a "formal, legally binding and irreversible way". Giving greater powers to national parliaments to block EU legislation.

What Tusk has offered: "The references to an ever closer union among the peoples are... compatible with different paths of integration being available for different member states and do not compel all member states to aim for a common destination.

"It is recognised that the United Kingdom... is not committed to further political integration into the European Union.

"Where reasoned opinions on the non-compliance of a draft union legislative act with the principle of subsidiarity, sent within 12 weeks from the transmission of that draft, represent more than 55% of the votes allocated to the national parliaments, the council presidency will include the item on the agenda of the council for a comprehensive discussion."

Gavin Hewitt: The words "ever closer union" stay, but they have been interpreted as not meaning political integration or new powers for the EU. In essence, this is what the government wanted - the EU accepts there are not just different speeds to European integration but countries may have different destinations. What the government did not get was recognition the EU was a union with "multiple currencies".

Mr Cameron has won inclusion of a "red-card" mechanism, a new power. If 55% of national parliaments agree, they could effectively block or veto a commission proposal. The question is how likely is this red card system to be used. A much weaker "yellow card" was only used twice. The red-card mechanism depends crucially on building alliances, and the UK has not always been successful at that.

In these negotiations, some key areas seem to have been dropped. There will be no repatriation of EU social and employment law, which was a 2010 manifesto commitment. There will be no changes to the working-hours directive. The sceptics will argue that over sovereignty, the UK has not won back control over its affairs.

Chris Morris: The idea that different member states will move at different speeds and on "different paths" was already widely accepted. Britain won't be in the inner core, but we knew that already. There is also specific language in these draft proposals that encourages the eurozone to integrate further - as most governments accept that it must.

The idea of a red card for national parliaments makes a nice headline, but it may not make much difference in practice. It would still be easier to block legislation in the Council of Ministers (threshold 35%) than under the new proposal in which 55% of EU parliaments would have to club together to make an objection.

Donald Tusk met the British prime minister over the weekend

Migrants and welfare benefits

What Cameron wanted: The Conservative manifesto said: "We will insist that EU migrants who want to claim tax credits and child benefit must live here and contribute to our country for a minimum of four years." It also proposed a "new residency requirement for social housing, so that EU migrants cannot even be considered for a council house unless they have been living in an area for at least four years".

The manifesto also pledged to "end the ability of EU jobseekers to claim any job-seeking benefits at all", adding that "if jobseekers have not found a job within six months, they will be required to leave".

Mr Cameron also wanted to prevent EU migrant workers in the UK sending child benefit or child tax credit money home. "If an EU migrant's child is living abroad, then they should receive no child benefit or child tax credit, no matter how long they have worked in the UK and no matter how much tax they have paid," says the Tory manifesto.

What Tusk has offered:"[New legislation will] provide for an alert and safeguard mechanism that responds to situations of inflows of workers from other member states of an exceptional magnitude over an extended period of time… the implementing act would authorise the member state to limit the access of union workers newly entering its labour market to in-work benefits for a total of up to four years from the commencement of employment."

Gavin Hewitt: This is the "emergency brake" there has been much talk about. If there were excessive strain on the welfare system, in-work benefits could be denied to EU workers for four years. This is, essentially, what Mr Cameron wanted, albeit with access to benefits gradually increasing over time.

The government had promised to reduce the numbers of EU migrants and believes the UK's current benefits act as a pull factor. The EU has agreed it would be "justified" to trigger an emergency brake without delay after the referendum if the UK votes to stay in the EU.

But there are questions here:

For how long would the emergency brake stay in place? Four years - but who would judge whether an emergency no longer existed? Who would pull or release the brake?

What would happen to migration when the brake was lifted? Under the proposal, the access to benefits would gradually increase - so how much of a disincentive to come to the UK would that prove to be?

Mr Cameron has failed in his demand to ban migrant workers from sending child benefit money back home, but they would get a lower level of payments if the cost of living in the country where the child lives is lower.

The government has already reached an agreement on out-of-work benefits. Newly arrived EU migrants are banned from claiming jobseeker's allowance for three months. If they have not found a job within six months they will be required to leave. EU migrant workers in the UK who lose their job, through no fault of their own, are entitled to the same benefits as UK citizens, including jobseekers allowance and housing benefit, for six months.

The Tusk letter does not mention changes to social housing entitlement but they were never part of Mr Cameron's preliminary negotiations.

Chris Morris: There will still be considerable opposition in Eastern Europe towards anything that smacks of discrimination against their citizens. Little wonder that David Cameron's next stop on his tour of Europe will be a return to Warsaw on Friday. He has some persuading still to do.

There is also a lot of detail surrounding the emergency brake proposal that remains vague, and there's likely to be some difficult late night debate ahead. The basic premise - that the UK can treat nationals from other EU countries differently, even if only for a short time - is certainly a departure from the status quo. Other countries may look to take advantage of this as well, and that will make some EU officials nervous.

Economic governance or safeguarding interests of countries outside the eurozone

What Cameron wanted: An explicit recognition that the euro is not the only currency of the European Union, to ensure countries outside the eurozone are not materially disadvantaged. He also wanted safeguards that steps to further financial union cannot be imposed on non-eurozone members and the UK will not have to contribute to eurozone bailouts.

What Tusk offered: "Measures, the purpose of which is to further deepen the economic and monetary union, will be voluntary for member states whose currency is not the euro.

"Mutual respect between member states participating or not in the operation of the euro area will be ensured.

"Legal acts... [between eurozone countries] shall respect the internal market."

Gavin Hewitt: The UK government wanted safeguards that as the eurozone integrated further, it did not take decisions that threatened the essential interests of those outside the eurozone, such as Britain. Key British interests are the single market and the City.

Crucially, much of the detail here has not been worked out. It is not clear what rights non-eurozone countries have beyond being consulted and not having to pay for the financial stability of the euro. This could well be a source of friction at the forthcoming summit.

Chris Morris: It's just a hunch, but this could still be the issue that has EU leaders haggling into the early hours when they convene for a summit later this month. It threatened to delay the release of Mr Tusk's draft proposals today, as French President Francois Hollande sought assurances that Britain would not hold any kind of veto over eurozone business.

Another emergency brake would be deployed here, but it is not entirely clear what would happen if consensus between euro ins and outs proved impossible. This is such an important long-term issue that there may be those who say that further clarity is essential before they can sign up to a final deal.

Competitiveness

What Cameron wanted: A target for the reduction of the "burden" of excessive regulation and extending the single market

What Tusk offered: "The EU must increase efforts towards enhancing competitiveness, along the lines set out in the Declaration of the European Council on competitiveness. To this end the relevant EU institutions and the member states will make all efforts to strengthen the internal market….this means lowering administrative burdens."

Gavin Hewitt: This was the least controversial of the government's demands. The spirit of the times in Brussels is to do less but better. Such statements do not always accord with reality, however. Certainly Mr Cameron has been at the forefront of arguing for less red tape and less regulation on business.

Chris Morris: Who doesn't want a more competitive Europe? The question is how best you achieve it. These proposals envisage a declaration that the EU would work towards greater integration of the single market. But they've said that before, so it doesn't feel all that new.

There is also provision for an annual audit of EU regulation with the aim of reducing red tape - but, again, that is already a stated priority of the current European Commission. This feels a little bit like more of the same, but officials argue that it needed clarifying in the context of the EU debate in the UK.

Further reading on the UK's EU referendum

Referendum timeline: What will happen when?

Guide: All you need to know about the referendum

The view from Europe: What's in it for the others?