UK's draft EU deal: What do red and yellow cards mean?

- Published

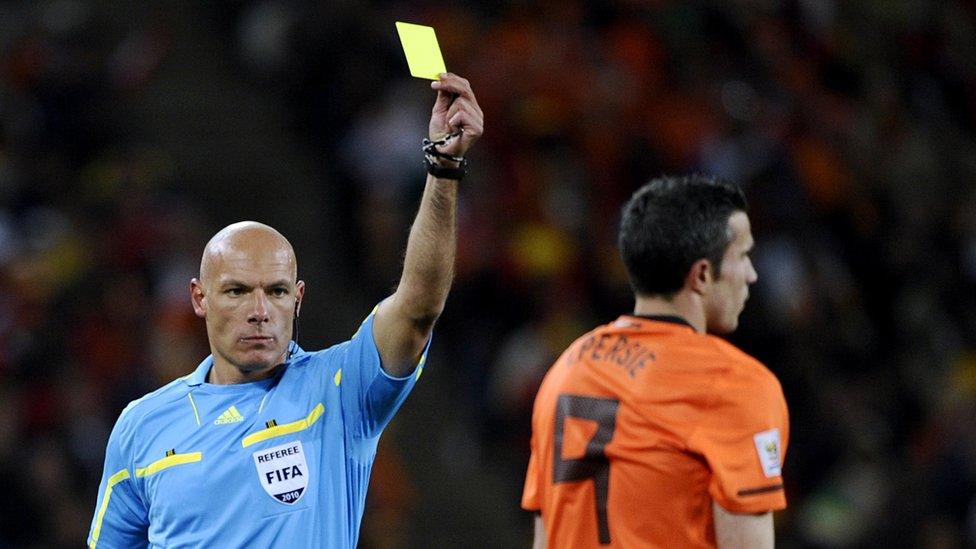

The yellow card is a warning - but red would mean "sending off" an EU law

Football fans are all too familiar with yellow and red cards. But in the EU it's a bit more complicated.

An important element of UK Prime Minister David Cameron's EU proposals is the right of national parliaments to block EU laws.

It would mean showing a "red card" to the European Commission - going beyond the current yellow-card mechanism.

The red card does not yet exist - but it might, if EU leaders accept the proposed changes, external described by European Council President Donald Tusk.

What does the yellow card do?

It was introduced in the EU's 2009 Lisbon Treaty, to address concerns about "subsidiarity" - the principle the EU should not legislate on matters best dealt with at local, regional or national level.

The European Commission has sole responsibility for initiating EU laws. Critics accuse it of over-regulating, tying up governments and businesses in too much red tape.

The yellow-card system, external system gives each national parliament two votes - making a total of 56. (There are 28 member states.)

To trigger the yellow card, a minimum of 18 votes is needed. The parliaments also have to send the commission "reasoned opinions" spelling out why they object to a draft law. The deadline for doing so is eight weeks.

Once triggered, the commission may decide to keep, amend or withdraw the draft text - and must explain its decision. But the yellow card is no automatic block on a proposal.

National MPs have to work together to successfully challenge EU legislation

Is it used much?

The yellow card has been used twice.

In May 2012, the commission withdrew a draft law, Monti II, that would have introduced a new EU mechanism for settling labour disputes, after 12 parliaments objected.

According to Ian Cooper, a political analyst at Cambridge University, the Danish parliament led that yellow-card initiative. National MPs had co-ordinated their arguments face-to-face, helped by their representatives in Brussels, he said in a blog, external.

In October 2013, the UK was among 11 parliaments that objected to a commission proposal to create an EU public prosecutor's office. On that occasion, the commission decided to maintain the proposal, despite the yellow card.

An orange-card procedure also exists, but has not been used yet. If a majority of national parliaments jointly oppose a draft law, the commission has to review it.

The failure to use the orange card shows that national MPs are focused on national interests, and "struggle to find a common stance on European issues", Agata Gostynska of the Centre for European Reform told the BBC.

What could change with a red card?

Mr Cameron says a red-card mechanism would enhance the sovereignty of national parliaments, enabling them, jointly, to "stop unwanted legislative proposals".

The red card would force the commission to amend or drop the draft law to accommodate national concerns.

But the document from Mr Tusk says the blocking mechanism would apply only in areas where legislation might better be done at national level, under the subsidiarity principle, and not to EU proposals more generally.

And some of Mr Tusk's language may be viewed by critics as vague and open to interpretation, the BBC's Simon Wilson reports. Principles will be "duly taken into account" and "appropriate arrangements" will be made, his proposal says.

Instead of eight weeks, national parliaments would have 12 weeks to make up their minds about a draft law from the commission.

But the threshold for triggering the red card would be 55% of the total votes allocated to the parliaments.

If that is achieved, Mr Tusk suggests, the complaint will be put on the agenda of the next council meeting, where EU governments are represented, for a "comprehensive discussion".

The red card "could ensure that EU institutions listen more to national parliaments' concerns", Agata Gostynska said.

But using the card system also requires MPs to spend more time examining European issues, she said.

"They usually prefer to look at domestic issues, which affect voters directly," she added.

- Published2 February 2016

- Published30 December 2020

- Published20 February 2016

- Published1 February 2016