EU referendum: Cameron's options for enhancing sovereignty

- Published

Governments rarely perform miracles but they do try to square circles. And that is what David Cameron's ministers are attempting right now with Britain's constitution.

They are looking for a way of asserting the sovereignty and authority of parliament over the EU in a way that convinces voters - and Boris Johnson - that Britain's relationship with the continent is changing.

But they need to do this without claiming that UK law has primacy over EU law, something that would be tantamount to leaving the EU. As you might imagine, this is not proving an easy piece of constitutional carpentry.

Clever minds in Whitehall are looking at two potential options, both of which would involve parliament giving greater authority to the Supreme Court to question rulings coming from the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in Luxembourg.

One option would involve the Supreme Court assessing decisions by the ECJ and considering whether they breach the fundamental principles of Britain's constitutional norms that have been laid down over the centuries in various Acts of Parliament and common law. This would follow a similar path to the German constitutional court which can assess whether ECJ decisions challenge Germany's constitution.

The problem with this option, of course, is that Britain does not have a single, codified constitution and so legal comparisons would be complex to say the least.

And there is also the small problem that placing British constitutional traditions ahead of EU law would effectively leave the UK in breach of the many treaties it has signed over the years as a member of the European Union. If you don't sign up to the club rules, you can't be a member of the club.

'Judicial activism'

So a second option is being considered that some see as being perhaps more feasible. This would again involve parliament beefing up the authority of the Supreme Court to question rulings coming from the European Court of Justice.

But - and here's the clever part - the Supreme Court would do this only in exceptional circumstances if it thought the judges in Luxembourg were breaching not UK law, but EU law.

Crucially, the Supreme Court would not be questioning the supremacy of EU law. It would simply be ensuring that the UK obeyed the EU treaties which it had signed up to, rather than how those treaties were being interpreted by judges in Luxembourg.

Now this might sound mad, or at the very least counter-intuitive. But national courts like the UK Supreme Court have already questioned what some see as the "judicial activism" of the European Court of Justice. Some courts think that the ECJ has on occasion exceeded its jurisdiction and made judgements that are not based on EU treaties.

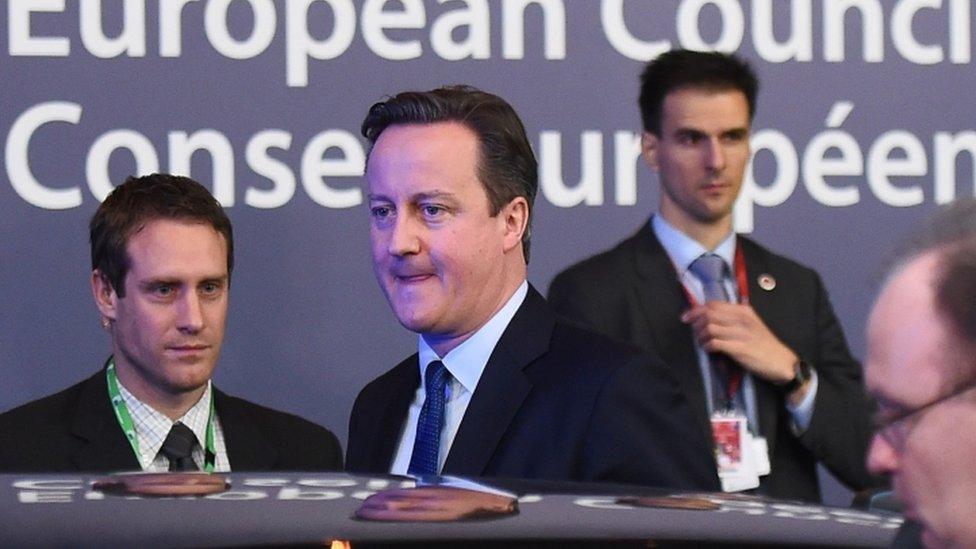

Boris Johnson has yet to be persuaded of the case for remaining in the EU

In a case last year, the Supreme Court was asked to decide whether Home Secretary Theresa May was legally able to deprive a Vietnamese man of his UK citizenship because he was considered by the security services to be a threat to national security.

The European Court of Justice has in various judgements challenged such decisions because it believes that EU citizenship is dependent on national citizenship and therefore it has a right to poke its nose in decisions like this.

'Go stick'

But the Supreme Court questioned this judicial activism which it considered was not based on any EU treaty text. In a judgement on the so-called Pham case, on 25 March 2015, the judges said in, paragraph 90:

"A domestic court faces a particular dilemma if, in the face of the clear language of a Treaty and of associated declarations and decisions, such as those mentioned in paras 86-89, the Court of Justice reaches a decision which oversteps jurisdictional limits which Member States have clearly set at the European Treaty level and which are reflected domestically in their constitutional arrangements. But, unless the Court of Justice has had conferred upon it under domestic law unlimited as well as unappealable power to determine and expand the scope of European law, irrespective of what the Member States clearly agreed, a domestic court must ultimately decide for itself what is consistent with its own domestic constitutional arrangements, including in the case of the 1972 Act what jurisdictional limits exist under the European Treaties and upon the competence conferred on European institutions including the Court of Justice."

Now that might read as a lot of rather wordy legalese but it is in fact the highest court of the land very gently and very politely telling its counterpart in Luxembourg to go stick.

This led the legal expert, Professor Derrick Wyatt QC, to conclude in a lecture on November 2015 that:

"There is no doubt that some of the case-law of the Court of Justice has been regarded by the supreme courts of Member States as exceeding the jurisdiction conferred upon it, and in so doing encroaching in an unauthorised way upon the national legal systems. UK judges have expressed concerns of precisely this kind. In my mind they have been right to do so."

He added: "Leaving the protection of the UK constitution to UK judges is not necessarily at odds with the UK government considering whether something further might be done in support of the role of the national judiciary. That "something further" might include providing statutory recognition of the limits of EU law supremacy under the European Communities Act. It is understandable that the prime minister might think that the present is an appropriate time for review of the UK constitutional position."

'Nuclear weapon'

And Professor Wyatt is not alone. Anthony Speaight QC, who served on the government's Commission on a UK Bill of Rights, gave evidence to MPs on the All Party Group on the Rule of Law this month and he told them in a written submission:

"It would do no violence to UK legal principles, and arguably would be to perfect and enhance them, if Parliament were to amend (section 2 of the European Communities Act 1972) to clarify that the domestic courts are not to enforce EU instruments and decisions if they find them to be outside EU competences, and that ECJ decisions as to whether acts are within or without competence are to be no more than persuasive authority."

Mr Speaight accepted that such a power would be "a nuclear weapon" that the Supreme Court would be reluctant to use.

But he concluded:

"It might be judged that the theoretical existence of the review in the hands of a court with so high an international reputation as the UK Supreme Court would act as a salutary warning to EU institutions to respect the limits of competence and subsidiarity."

Now this option, of beefing up the powers of the Supreme Court, is not without its problems.

Some lawyers argue that there is no distinction between EU treaties and how the ECJ interprets those treaties.

The former attorney general Dominic Grieve told BBC Radio 4's The World at One his week that the attempt was pointless because ultimately the ECJ has the final say.

Some MPs think that judge-led law is just as bad coming from the UK Supreme Court as it is from the European Court. And politically there is no guarantee that a rarely-used constitutional long-stop would be enough to persuade London Mayor Boris Johnson to vote to remain in the EU.

But, right now, it appears to be the only game in town and it is the one the government is playing.

- Published10 February 2016

- Published9 February 2016