EU referendum: Can Switzerland show UK route to Brexit?

- Published

Switzerland is surrounded by the EU, but not in it

As Britain agonises over whether to stay in or leave the EU, many UK voters are looking to Switzerland's example to help them make up their minds.

The Swiss voted in December 1992 not to join the European Economic Area. At the time, joining the EEA would have been a first step towards full EU membership.

Instead, Switzerland, which sells over 50% of its exports to the EU, agreed more than 120 bilateral agreements with Brussels designed to secure Swiss access to Europe's markets.

Imogen Foulkes reports from Geneva: ''Swiss relations with the EU are tricky''

It has, political analyst Dieter Freiburghaus says, worked quite well.

"Switzerland was only interested in the economic aspect of European integration, and that we got: we got access to the internal market. So our economy had a lot of gains. We have the cake and we eat it… at the moment."

EU referendum live reporting- latest updates

Switzerland - BBC country profile

EU referendum - all you need to know

The Swiss economy has been ranked the world's most competitive.

Unemployment, while rising, is low by European standards, and being outside the EU has allowed Switzerland to clinch its own personal trade deal with China, something EU members cannot do individually.

But Swiss business leaders are quick to caution against seeing Switzerland's example, which took many long years of haggling, as ideal.

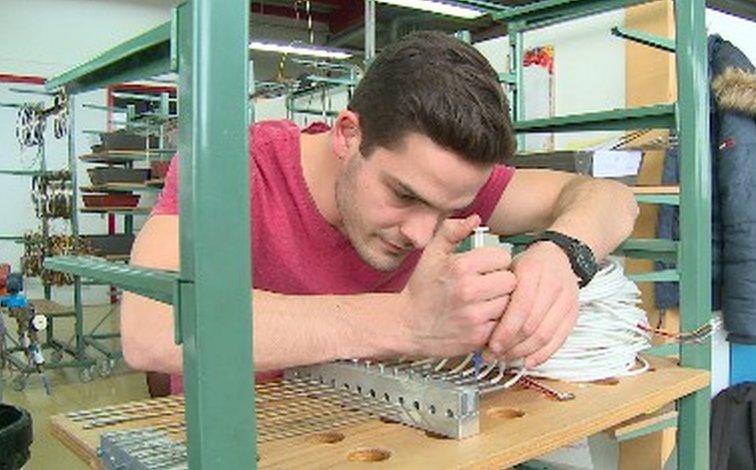

Swiss firm Rueger sells half of its precision engineering products to the EU

"Sometimes you get a good piece of a good agreement, sometimes you don't get it at all," says Jan Atteslander, European Director of the Swiss Business Federation, EconomieSuisse. "It has advantages and disadvantages economically. You can't have it all."

Swiss businesses, while having access to Europe's markets, are not on a level playing field with their EU counterparts.

Precision engineering company Rueger sells 50% of its products to the EU.

"Compare just the logistic costs," explains managing director Bernard Rueger. "It's simple in Europe, in terms of administration, in terms of tax, they are working in the same unique market, whereas here in Switzerland we have to export our goods."

"And it's probably 4-6% more costly exporting from Switzerland."

When it comes to exports Swiss companies are not on a level playing field with their EU competitors

Add to that the overvaluation of the Swiss franc and Switzerland's products start to become very expensive. That is why Rueger now has a plant in the Netherlands, offering jobs that might otherwise have stayed in Switzerland.

And it is why the managing director, from a purely business standpoint, has some blunt advice for his British colleagues. "My first advice is to vote to stay in," he says. "It's a crucial market."

If the vote goes the other way, Mr Rueger believes, many British firms will have "no choice" but to move some production capacity inside the European Union proper.

Cherry-picking

While Switzerland may have wanted only economic union with Europe, political ties have become ever closer over the years.

Unemployment in Switzerland is low at 3.8%

A central plank of Brussels' negotiating tactic with the Swiss was to insist that they could not "cherry-pick" the parts of the EU they thought would be most advantageous, such as its trade area.

Switzerland has signed up to free movement of people, with all the benefits that implies for workers and their families from the EU, and to Schengen open borders, all without ever being at the negotiating table at which those policies were drafted.

Switzerland contributes billions of dollars to EU projects on research, education, culture and security. The Swiss even paid 1.3bn Swiss francs (€1.18bn; £910m) to the EU enlargement fund, designed to support new members from Eastern Europe.

Brussels, we have a problem

But the adoption of all that policy caused political problems. Two years ago Swiss voters, concerned about rising immigration, narrowly supported a proposal to limit the number of workers coming in from the EU, effectively abandoning Switzerland's commitment to free movement of people.

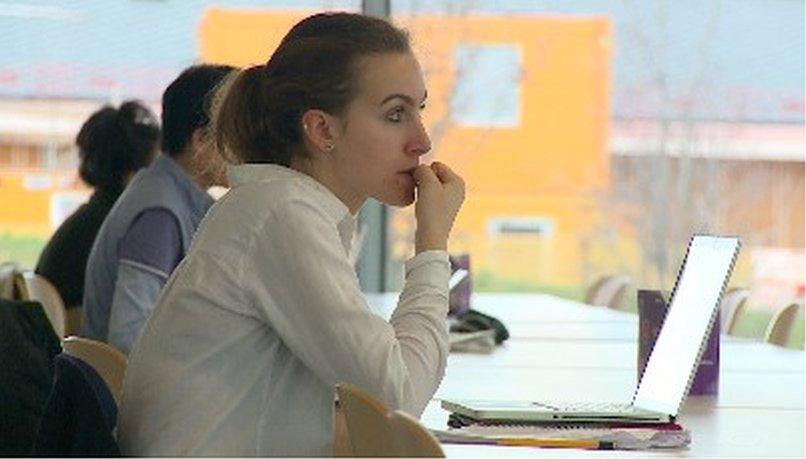

Swiss students were kicked out of European Exchange Projects after the 2014 referendum

Brussels made good on its no-cherry-picking policy and retaliated swiftly.

Swiss universities were blocked from European research projects. Swiss students were denied access to the Erasmus exchange programme.

"Being kicked out of that scheme represents a real handicap," says Andreas Mortensen, Vice-Provost of Switzerland's prestigious Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne.

"As a researcher, you would certainly rather want to remain within the EU. The benefits from being part of the EU research community are the intellectual oomph and the opportunities for collaboration."

Student Zilia Schwartz, who had just been accepted on an Erasmus exchange to the Netherlands, was affected too.

"I was about to go on my exchange and then there was this vote, and it was like: 'Oh maybe you can't go'," she said.

Swiss voters in 2014 narrowly backed the Yes campaign (R) to "stop mass immigration"

In the end the Swiss government solved Zilia Schwartz's problem by throwing money at it, paying each European university separately to admit Swiss students.

Waiting for Brexit

Switzerland's hard-won bilateral deals are now in danger of unravelling over the question of its participation in free movement of people.

The Swiss government has not yet introduced any restrictions on EU workers. It is still hoping to find a way to do so that won't bring further punishment from Brussels.

But the signs are not good: as well as the stalled participation in education and research projects, key trade agreements on electricity and financial services (a much longed-for prize for the Swiss) have been frozen.

There will be no deal for Switzerland, the EU has signalled, until after the UK's in-out referendum.

If Brussels is reluctant to offer a member like the UK concessions on social benefits for EU migrants, how likely is it to allow a non-member to restrict EU immigration altogether?

"Everyone talks about Brexit but no-one has said what will happen afterwards," warns Dieter Freiburghaus.

"What about the treaties with the EU? Switzerland has 120 agreements. Will Britain begin, the day after, to negotiate 120 agreements? Will it join the European Economic Area? It is so unclear."

The message from Switzerland appears to be that survival outside the EU is doable, but certainly not easy.

- Published19 February 2016

- Published18 February 2016

- Published18 February 2016

- Published5 January 2016

- Published17 February 2016