Reality Check: How plausible is second EU referendum?

- Published

There is a known known: On 23 June voters in the UK will decide whether to remain in the European Union or leave.

That is the referendum choice.

But then, to deploy former US defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld's famously cryptic phrase about the missing evidence for Iraq's weapons of mass destruction, there are known unknowns: If Britain votes to leave the EU what terms of exit would Britain get?

How would EU leaders react?

Would they plead for Britain to stay, offer a fresh negotiation and hope the UK votes to stay in a second referendum?

That is the scenario Leave campaigners want to paint.

Nervous voters

Former Tory leader Michael Howard is the latest - and most politically hefty - "leaver" to claim a second deal and referendum would be possible.

Mr Howard said a no vote would "shake EU leaders out of their complacency".

In the frenzied panic that would follow a vote to leave, his argument goes, EU leaders would have to come up with a better deal in their desperation to keep the UK in the club.

Lord Howard says EU nations "quite likely" to reconsider position if the UK voted to leave

After all, European leaders have spent the last months saying how dreadful it would be for one of its richest and biggest economies to check out.

Talking up the chances of a second referendum has been a central tactic of the leave campaigns for months.

In January the director of Vote Leave, Dominic Cummings, told the Economist magazine the UK would not have to trigger Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty immediately after a leave vote (the process that begins a member state's two year exit from the EU) and the final terms of Brexit could be put to voters in a second referendum.

The tactic of talking up a second referendum is clear: Reassure nervous voters the referendum is a stepping stone not a leap into the unknown.

So, is this plausible?

'No second chances'

Let's look at what people in Brussels are saying.

For a start, David Cameron has said the idea of doing this all again is "for the birds".

The UK government has said a Leave vote would mean going to Brussels and invoking Article 50 immediately.

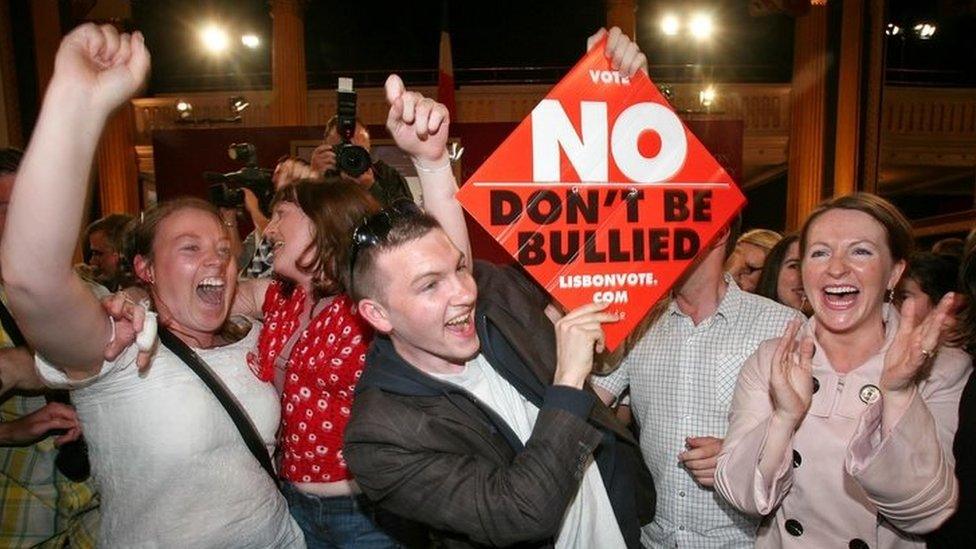

Ireland rejected the Lisbon Treaty at the first time of asking

And let's return to the ballot paper.

There is nothing on it that would give the prime minister a mandate to try and renegotiate again.

Even if he tried to do that, the other 27 EU leaders would have to agree to restart renegotiations with Britain.

Now that's not impossible.

But from the statements of key EU players since the renegotiation deal was done it would seem very unlikely.

For instance, last week Belgium's Prime Minister Charles Michel said bluntly there were "no second chances" on this.

Days later, in a European Parliament debate discussing the UK agreement, politicians queued up to deliver the same message.

Referendum re-runs

European Council President Donald Tusk said if a majority in Britain vote to leave, "that is what will happen".

Manfred Weber MEP, the leader of the largest group in the Parliament (the centre-right EPP) spelt it out: "If people are being told in the United Kingdom that if they say no they will get a better deal, we have to say to them very clearly the agreement on the table is the agreement. There will be no follow up negotiations."

Liberal group leader Guy Verhofstadt said the same: "Don't think after voting a no you can come back to the negotiation table," he said. "This is about in or out. It's one or the other."

A second renegotiation?

"Non, nein, nee" has been the message from Brussels.

And the deal agreed by EU leaders last week explicitly says this is it.

"It is understood that, should the result of the referendum in the United Kingdom be for it to leave the European Union, the set of arrangements referred to in paragraph 2 above will cease to exist," reads the text.

But wait a minute - what about all those European referendums re-run to get a different result?

Exasperated derision

After the Maastricht Treaty was rejected by voters in Denmark a batch of concessions were made, a second vote was held and the Treaty passed.

Ireland's initial rejection of the Lisbon Treaty was also followed by a second referendum and a different result.

However, these referendums were on fundamental EU treaty change.

Because the EU needs unanimous approval for its primary law to be changed these rejections stalled the whole EU machine and a fix had to be found. The UK situation now is different.

This is a process the British government has chosen to begin.

A UK exit would undoubtedly cause some anguish in the EU but it would not stop the project moving forward.

There is also real concern in Brussels that any more special treatment for the UK could be contagious, a green light to other member states to try the same.

Of course, only once the result is known will any of this become completely clear. If it's a vote to leave the EU the reality of the political crisis that would follow in Brussels may change minds.

But for now, the suggestion the UK would be allowed back to the negotiating table is being met here in Brussels with exasperated derision.

READ MORE: The truth behind claims in the EU debate

- Published26 February 2016

- Published30 December 2020

- Published24 February 2016