EU referendum: Preston and the chocolate factory

- Published

How are voters in Labour's heartlands approaching the EU referendum? And why do more women than men say they are still undecided on how they will vote?

For the latest stage of Newsnight's Referendum Road series, we went to Preston, a city that's aiming to be the third largest in north-west England and a model for the Northern Powerhouse.

About 15% of Preston's population is of Asian background, and they were traditionally a vital part of the workforce at Beech's chocolate factory, established in 1920.

But they've been replaced by newer migrants, mainly Poles who've come to Britain under the EU's freedom of movement agreement and now sit beside the conveyor belt packing chocolates next to local British workers, many of whom have worked in the factory for decades.

"I was 16 when I started," Denise Wareing told me. "I could smell the chocolate. I thought 'I wouldn't mind working there'."

The past looms large here, not least because Beech's chocolates are still produced in the original factory, with much of the same machinery. Many of their competitors have moved their plants to eastern Europe where labour is cheaper.

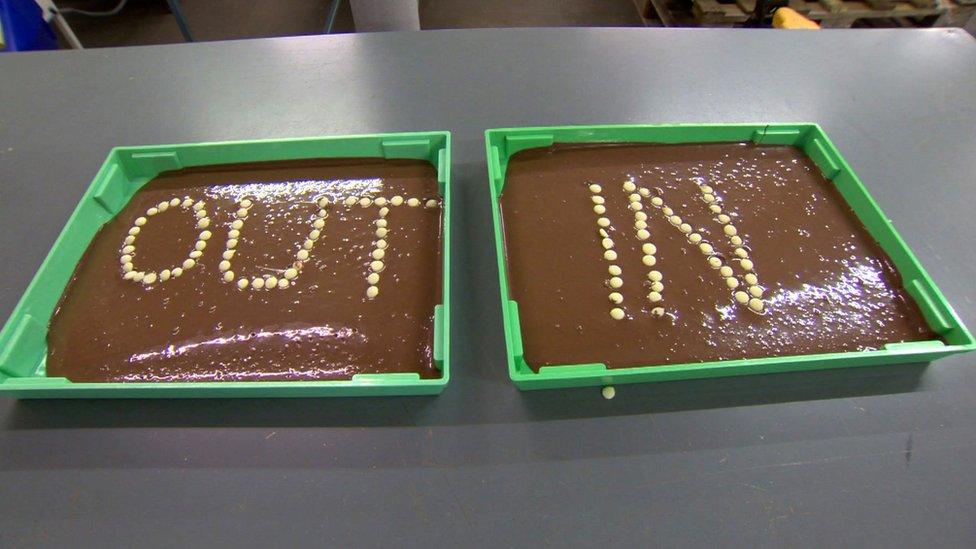

But the past figures in another way too. Many of the workers hark back to a time when they believe Britain was a better place. Fairly or unfairly, they blame the EU for the change.

Preparing Turkish delight for coating in chocolate at Beech's

In a recent poll, almost a quarter of semi-skilled and unskilled workers said they still did not know how they would vote in June.

There's been little shift in the numbers who say they already know how they will vote, either to leave or stay, so the undecideds are a key group in the referendum.

Some analysts predict that when pushed to a decision, more undecided voters say they will choose to remain than to leave.

In the factory, many of the women I spoke to told me they were undecided - but when pressed, the majority said they thought they wanted to vote out.

Life would be sweeter outside the EU, they believe.

More from Newsnight on the EU referendum:

It is an unscientific poll of course, but their reasons are illuminating. For them, more than anything, this is about controlling Britain's borders and protecting an over-stretched NHS, which they blame on the flow of migrant workers to the UK.

It is worth noting Preston hasn't experienced the major migrant inflow that some parts of the country have.

"The NHS is stretched to the maximum… more people are coming in and it will be stretched even further, and I think the borders need to be controlled a bit more," said Gill Collum at Beech's.

Tina Caulton at work in Beech's chocolate factory

Tina Caulton talked of eight non-British people who arrived in the dentist as she awaited an appointment. She said she was paying for her treatment, while none of them were. "They're getting it for free."

None wanted to appear racist and they sit happily beside their Polish colleagues. As Tracy Parkin put it: "I like the Polish, the people, they are very nice people." But many of the workers want to stop the flow.

Denise Wareing, preparing Turkish delight to be enrobed in chocolate, worries if Turkey joins the EU, even more people will want to come to the UK. "Enough's enough," she said. "We have to draw a line somewhere."

Disconnect

Barbara Collins has just retired after 50 years of chocolate-making. She understands the benefits of a diverse workforce.

"We rely on people from different nationalities. We couldn't get the orders out without them. But I'm concerned about how many we are letting in."

The pro-Remain camp flags up the benefits of being part of the EU. It is argued that 350,000 jobs in north-west England are linked to trade with the EU, 25,000 jobs have been created or protected by EU investment projects here in the last five years, and the region received £996m in European structural funds between 2007 and 2013.

But there's a disconnect between those statistics and perceived reality. The factory workers would have been traditional Labour voters in the past - their parents and grandparents voted for the party almost without question.

But historical ties to parties have become more muted.

The official Labour Party stance is to campaign for a remain vote. That's falling on deaf ears in this factory.

Many of the mainly female workforce told me they've stopped voting because they don't trust the politicians.

And when you don't trust the political class, you're not going to listen to them when they tell you that the economy will tank if Britain leaves the EU. Or that Britain's security will be under threat.

This isn't a picture of general opinion in Preston, but a snapshot of a voter group who feel disenfranchised and left behind in the globalised world.

And it's difficult to imagine any arguments in favour of the EU ever being a sweet choice for them.

More from Newsnight on the EU referendum: