EU referendum: The non-Britons planning to vote

- Published

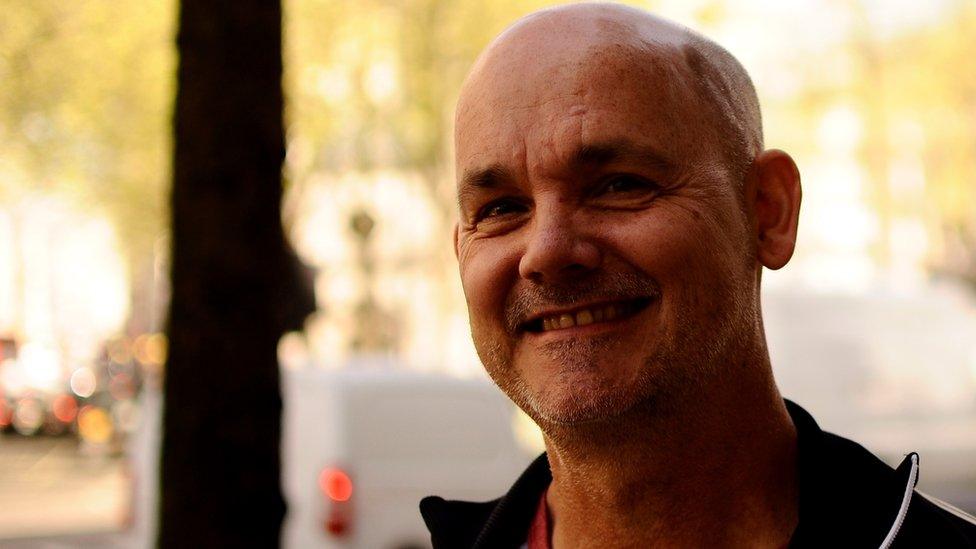

Australian Michael Ingle says the referendum has ramifications beyond Britain

It might seem peculiar that a young Australian here in Britain on a two-year working holiday is allowed to have a say on whether the UK should leave the European Union.

But Michael Ingle, a 27-year-old physiotherapist living in Surrey, defends his right to participate in the 23 June referendum.

He says that as a taxpayer, and a citizen of the Commonwealth, what happens to Britain is important to him and will have ramifications for the wider world well beyond the cliffs of Dover.

"It's not just about Britain for me, which is why I've taken an interest in it," Mr Ingle, from Sydney, says.

"It's about the West and the stability of this continent."

'Important decisions'

As a hangover from the days of empire, when so-called "British subjects" were included in the parliamentary franchise, Commonwealth citizens resident in the UK without British nationality retain the right to vote in elections.

Estimates based on the 2011 census put the number of Commonwealth citizens eligible to vote in the forthcoming referendum at between 894,000, external and more than 960,000, external.

They join Irish citizens as the only non-Brits allowed to vote in what David Cameron has called a "once in a generation" decision.

A petition is calling for only British citizens to be allowed to vote in the poll

This has drawn the ire of groups including Migration Watch UK.

Its chair, Lord Green of Deddington, says that "important decisions about Britain should be taken by those who are British citizens and only by them".

A petition to parliament, external signed by more than 40,000 people, meanwhile, has claimed that allowing non-Brits to vote would bias the result towards the Remain side, especially given that the Commonwealth countries of Cyprus and Malta are also in the EU.

Diverse group

But regardless of whether one agrees with the voting rules, such claims treat Commonwealth voters as a homogenous bloc of sorts, destined to vote in the same way.

This obscures the fact that Commonwealth citizens living in Britain come from a diverse range of 53 countries in all the world's time zones.

Voters of even the same age and nationality can have vastly different views on the subject at hand.

Take Farhan Samsudin and Zila Fawzi, two young Malaysian women living in London.

Farhan, who works in banking, says she will vote Remain on 23 June, despite what she says is the failure of either campaign to provide information on how the "Commonwealth constituency" might be affected by the result.

Farhan says both campaigns have lacked information on how Commonwealth citizens might be affected

She thinks the UK should strengthen its economic ties with Asian economies like Malaysia and sees membership of the EU as an obstacle in trade negotiations.

Yet, with no clear plans presented to her on how a post-EU Britain would approach the world, she says she'll vote to stay.

Zila, on the other hand, who is on a British government-funded scholarship, supports an EU exit.

Her vote will be pinned on hopes that immigration policy will change in a way that benefits Commonwealth citizens if the UK no longer has to abide by free movement within the EU.

'A real waste'

"Once they are out of the EU it would be easier, especially for us Malaysians, to come and work here," she says.

A postgraduate student at the London School of Economics, Zila is frustrated by the fact that any EU citizen is allowed to work in the UK, while highly educated Commonwealth citizens like her are turned away.

On this point, Farhan chimes in.

"The British government sponsors brilliant minds like her but they don't give any leeway for her to work here," she says, shaking her head. "It's a real waste."

Avenues for Commonwealth citizens to migrate to the UK have become increasingly slim since the abolition of working holiday visas (now limited to just a handful of countries under the Youth Mobility Scheme) and the post-study work visa, which allowed students to stay on for two years after the end of their course.

Foreign students from outside the EU, many of whom are from the Commonwealth, now have just four months to find a job if they want to stay.

The recent introduction of a £35,000 income threshold for non-EU skilled workers to settle in the UK in a bid to reduce net migration has led to further frustration and the spectre of mass deportations.

Immigration policy

Yet, while it would seem as though pro-Brexit campaigners could capitalise on the prickly issue of immigration in order to draw Commonwealth voters to their side, the issue is not so clear-cut.

Given that some of the constituencies that the Leave campaign are courting harbour anti-immigrant sentiment, making a pitch to Commonwealth voters to back an EU exit based on immigration potential could see it take a hit elsewhere, says Ralph Buckle, director of the Commonwealth Exchange think tank.

"Everyone has this number of what they think the right level of immigration is. It depends whether that number is high enough to include an increase [from] the Commonwealth."

The government's target of getting net migration under 100,000 annually also hovers ominously over any suggestion that more places could go to Commonwealth citizens if Brexit eventuated.

The official Vote Leave campaign has said Britain could have a "fairer" migration policy that would "make it easier for some to come, such as scientists and job-creators" if the UK left the EU.

Migration is still well above the government's 'tens of thousands' target

In February Vote Leave published a letter to David Cameron from community and business leaders with Commonwealth links criticising immigration policy.

"The descendants of the men who volunteered to fight for Britain in two world wars must stand aside in favour of people with no connection to the United Kingdom," they said.

But Labour MP Chuka Umunna, speaking for the Britain Stronger in Europe campaign, said that leaving the EU in order to end free movement would hurt everyone in Britain economically, including Commonwealth citizens.

"Commonwealth citizens living in the UK benefit from jobs, lower prices and financial security we get from being part of the world's largest single market.

"Commonwealth countries around the world, from Australia to Jamaica, are urging us to stay in the EU," he said.

In a newspaper article last August, Lord Howell, chairman of Commonwealth Exchange and a former Conservative minister, said the polarity of the EU question was "maddeningly oversimplified" for internationally-minded Commonwealth citizens.

He said the Leave campaign could not fall back on a "little England mantra", while the Remain camp would have to move away from "seeing the continent as the UK's only future".

'Second-class citizen'

Mark Sultana, a 48-year-old long-time UK resident who organises events for fellow Canadians living in London, sees both sides of the picture.

While he bemoans "all the wastage and all the subsidies" of the EU, he fears financial instability and losing the right to retire on the continent.

"The whole thing is so complicated," he says.

"I think ultimately even though I'm so anti all these things, so many things that the EU stands for… from the point of view of economic stability, the fact you're in it and that the world should be [becoming] a smaller place not a bigger place… [I would vote with] a grudging and qualified yes."

Mark also points out that the immigration argument means different things for different Commonwealth citizens.

Brad wants his children to be able to work in Europe when they're older

Canadians who live in the UK by virtue of European ancestry like himself, for example, might be fearful of losing that right in the case of a Brexit.

"For that generation of that ilk, who came here, the European Union is very important. If you have Brexit there's a whole lot of people who would have trouble coming here."

For Brad Argent, meanwhile, having to deal with UK visa hassles despite being married to an English woman makes him feel like "a second-class citizen".

The 50-year-old Australian, who works for an internet business, needs to wait for five years to get residency.

"Whereas if I'm from Europe I can just come over on the train and set up house," he says outside Australia's High Commission on the Strand in London, where he has come to renew his passport.

But Brad won't carry his these grievances to the ballot box, least of all because he does not want his British children to lose the right to work in the continent.

"I think a vote to leave just out of spite because I'm a member of the Commonwealth, whilst that might feel good for about five minutes, I think the longer term implications I would start to regret," he says.

With Commonwealth migrants unlikely to vote as a uniform bloc due to their divergent interests and circumstances, it appears either camp could still make a pitch to this 'constituency', which has largely been ignored in the debate thus far.

After all, a million votes are at stake.