EU Referendum and Whitby fish & chips: Batter in or out?

- Published

Whitby is famed for several things including its abbey, Whitby jet, Dracula and its quality fish and chips

People travel from around the world to sample Whitby's famous fish and chips. But some fear the EU referendum could damage the North Yorkshire town's dish.

Standing by his fryer in Whitby, Stuart Fusco points at a piece of fish on the counter, gleaming in its fresh coat of golden batter, and says: "The cod is from Iceland whilst the haddock over there is Scottish."

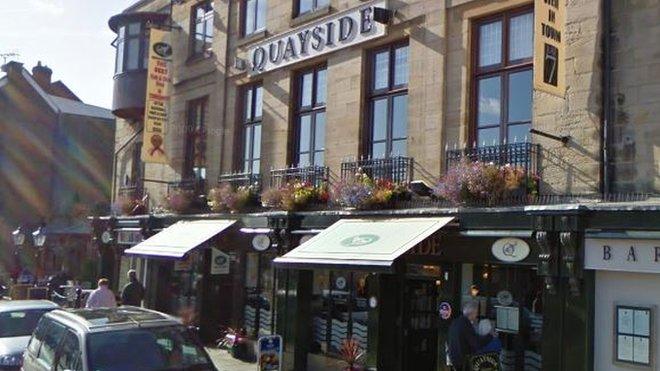

Mr Fusco, owner of the Quayside restaurant, continues: "At the moment I'm sat on the fence. I don't think either side has persuaded me.

"What I can tell you though is that this town is the capital of fish and chips. Last week we had people in from Holland and China because they know the stuff we produce is the best."

Stuart Fusco, of Quayside, calls Whitby "the capital of fish and chips"

Whitby's famous dish may have an international reputation but hardly any of the fish fried here is caught by local fishermen. And this theme is reflected across the wider British fishing industry.

Research from the House of Commons Library shows the British fishing fleet caught and landed more fish at UK ports in 1890 than it did in 2014, external.

When Queen Victoria sat on the throne, 598,000 tonnes of fish was landed at UK ports, compared with 451,000 tonnes in 2014. The current levels are similar to those during World War Two, when the conflict brought a massive fall from the amount of fish caught by British crews in the 1930s.

Fish and chip shops instead now import fish from places such as Norway, Iceland and Spain.

In Whitby harbour, the trawler Natalie B from Aberdeen carries a flag emblazoned with the logo of the group Fishing for Leave.

"That flag represents how 95% of UK fishermen feel," former Yorkshire trawler skipper Fred Normandale says.

The Natalie B is not one of his ships but Mr Normandale has no hesitation in blaming the European Union for the industry's demise.

"I think it's a tragedy there is no fish being landed in a town synonymous with fish and chips," he says.

As of this month there are six fishing vessels with Whitby registered as their home port, external.

In reality though, according to Mr Normandale, most crews land their catches at Peterhead in the North East of Scotland, the UK's biggest fishing port.

"When we joined the EU, one of our boats sailing out of a Yorkshire port was allowed to catch 100 tonnes of cod a year," he says.

"You could make a living off that. The problem is that quota is down to 20 tonnes and from a local business point of view it's just not viable."

The EU last year increased the amount of haddock UK fishermen are allowed to catch by 47%, a gesture Mr Normandale describes as insignificant.

"We need a 500% increase if we're to preserve what we've got left of the industry.

"The main reason I want to leave is that the EU is just a bottomless pit of money and it's all political horse trading.

"Our industry depends on the outcome of negotiations with people from Malta, Cyprus and that landlocked country Luxembourg. What do they know about fishing in the North Sea?"

Fred Normandale, a former trawler skipper, says fishing quotas need to rise drastically

The fish being served up at the Quayside restaurant might not be local but the chips certainly are.

"Stuart Fusco texts me his order for the next day at 23:00 every night", says David Hope, operations manager at Bland's Wholesalers in Ripon.

Every year 2,000 tonnes of potatoes pass through his warehouse, all of them grown in the fields of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire.

Mr Hope's working day starts at 01:30 as he takes stock of the latest consignment of potatoes, along with peppers and tomatoes from Holland and celery from Spain.

Bland's Wholesalers said the UK was "self-sufficient when it comes to spuds"

"Coming out of the EU could cost this business loads of money, so I want us to stay in," he says.

"The UK is self-sufficient when it comes to spuds so we'll be fine on that front, but nearly everything else that we sell here we have to import.

"If we start having to pay extra charges and tariffs to import stuff, then I'm afraid that extra cost is going to have to be passed on to the customer."

Back in Whitby, Mr Normandale sums up why politics and this referendum matters to him.

"Fishing was never just a job for me but a way of life - it was a good life until politics ruined it," he said.

The political decision the UK takes on 23 June will no doubt impact on many more lives, whatever the outcome of the referendum.

- Published30 December 2020

- Published29 April 2016

- Published22 February 2016

- Published22 January 2014

- Published27 April 2011

- Published15 April 2016

- Published27 April 2016