Reality Check: Your questions about trade and the economy

- Published

Lots of you have got in touch with the BBC about what a possible exit from the EU might mean for trade and the economy.

Roughly about 44% of the UK's exports go to the EU, give or take a couple of percentage points.

All 28 EU member states have access to the "single market". This means there are no tariffs, quotas or taxes on trade and the free movement of goods, services, capital and people.

If the UK voted to leave the EU, it would have to negotiate a new trade deal with it.

It could become part of the European Economic Area (EEA), a deal between Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein and the European Union.

These countries are not full members of the EU but have accepted EU regulations and its so-called four freedoms - the free movement of goods, services, people and capital (although the EU and Liechtenstein agreed an immigration quota so incomers did not affect the national identity of its tiny population).

Or it could take the example of Switzerland, which has its own bi-lateral agreement with the EU because its people rejected membership of the EEA in a referendum. However, Switzerland's agreement also requires the free movement of people but has less access for the services industry, a vital part of the UK's economy.

Some have suggested that the UK could take the example of Turkey, which is part of a customs union. That means it faces no tariffs (taxes or duties on imports and exports) or quotas on industrial goods it sends within the European Union but it has to apply the European Union's common external tariff, a set rate of tariffs on goods from outside the EU, on those goods too.

However, we've concluded that what a new deal would look like remains one of the biggest questions over a vote to leave the EU. The UK's current tariff-free, unrestricted trade deal with the EU would remain in place for at least the first two years of negotiations.

But no non-EU countries have negotiated tariff-free unrestricted trade with the EU without contributing to the EU budget and allowing unlimited EU migration.

In terms of the effects of a possible Brexit on the economy, we've checked the report issued by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) which suggested the UK leaving the European Union could lead to austerity being extended by two years.

We concluded that, if - like the IFS - you accept predictions that leaving the EU would cut economic growth, it is hard to imagine that would not hit the public finances.

We've also looked into what the ratings agencies have said. Standard and Poor's have said it would probably lower the UK's long-term credit rating. Fitch said it would review the UK's credit rating but did not now anticipate a downgrade in the immediate aftermath. Moody's said a vote to leave could lead to a negative outlook because of greater uncertainty and a weaker economy.

We have answered some specific questions about trade and the economy that BBC Radio 4's PM programme listeners asked us below.

The question: Margaret asks: "How are trade agreements negotiated and how long might they take? We presumably have little experience in this as it is done through the EU and has been for many years. Might one look south of the equator for their experiences or to BRICS (the grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) for example?"

The answer: Trade agreements can vary considerably in depth and breadth. Some are very comprehensive while others are much lighter, offering less market access. Consequently, the time it takes to negotiate trade deals can vary considerably.

For example, the EU first opened trade deal negotiations with the regional group Mercosur (which includes the countries Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela) in 2000 but negotiations are still ongoing. By contrast, negotiations for a free trade agreement between the EU and the Republic of Korea were launched in 2007 and the agreement was signed in 2010.

Currently, 52 countries are covered by existing EU trade deals. If the UK left the EU and wanted to retain preferential access to the markets of these countries, it would have to renegotiate trade deals with all of them. Some could take longer than others and it would not be up to the UK only, but also to the other countries which would base their negotiating positions on their own interests.

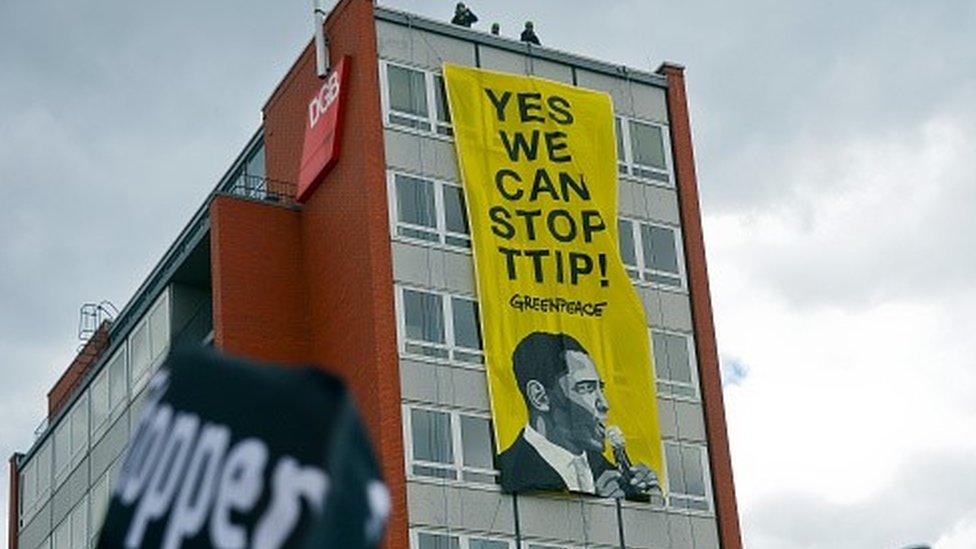

There is opposition to TTIP across Europe

The question: Kath asks: "Would the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) agreements still apply to the UK if we left the EU?"

The answer: TTIP is the EU-US agreement and it applies only to the EU countries. If the UK ceased to be an EU member, it would not apply to it. The UK could seek its own trade deal with the US post-Brexit, but that would have nothing to do with TTIP.

The question: Paul asks: "What is the current state of the EU's trade relations with major Commonwealth economies?"

The answer: The EU has already agreed, or is in the process of negotiating, trade deals with a majority of Commonwealth states. In 2015, 22% of imports to the EU came from Commonwealth countries and over 30% of EU exports went to the Commonwealth.

Since the UK became a member of the EU, UK trade with Commonwealth countries has fallen, while trade with EU countries has increased. A 2012 House of Commons Library report states that in 1973, UK trade in goods with the Commonwealth constituted roughly 18% of the UK's total trade in goods. By 2011, this figure stood at roughly 10%.

In that year, the Commonwealth accounted for an estimated 10% of all UK goods exports and 12% of all UK services exports. With regards to imports, the Commonwealth accounted for an estimated 7% of all UK goods imports and 10% of all UK services imports.

The UK's main trading partners (in terms of goods) within the Commonwealth are Canada, India, South Africa, and Australia, accounting for more than 60% of goods imports and exports from the Commonwealth in 2011.

The question: Bernard asks: "Do companies in Germany and France grumble about red tape making them uncompetitive?"

The answer: German and French businesses have expressed the need to cut bureaucracy and regulations within the EU. In 2015, governments of both countries were part of a joint call of 19 EU member states to the European Commission to reduce the burdens of EU regulations for businesses.

However, there is a general understanding that leaving the EU may do more harm than good to businesses and the economy. Germany, in particular, benefits from the single market as the largest member state both in terms of EU internal and external trade in goods. In 2015, Germany's share of EU exports to other member states was 22%. In France, the figure was 9% compared to UK's 6%.

In a recent survey of more than 700 British and German companies by the Bertelsmann Foundation, 83% of participating German businesses said that the UK should remain part of the European Union compared to 76% of British companies that took part in the poll. Close to 30% of German businesses with operations in the UK said that they would decrease their capacities in the UK in case of a Brexit.

Keep your questions coming by email (realitycheck@bbc.co.uk) or via Twitter @BBCRealityCheck, external and we'll answer as many as we can before 23 June.

Update 20 December 2016: This report has been amended to include details of Liechtenstein's immigration quota.

- Published19 May 2016

- Published18 April 2016

- Published14 August 2017

- Published22 February 2016