What next for the Conservative Party?

- Published

For David Cameron, the referendum had been the biggest political gamble in his career.

He called it and has lost it. It will define his legacy as prime minister. After 43 years, the UK is leaving the EU.

Some will celebrate, but many others will argue it was a huge miscalculation.

The referendum was called to preserve the unity of the Conservative Party in the face of an advance by UKIP. The prime minister wanted to stop his party "banging on about Europe". That mission clearly failed.

Many Conservatives who were in the Leave camp wanted David Cameron to continue. They argued in a letter before the result was known that he had a mandate to continue and was a force for stability.

But the prime minister, struggling with his emotions, announced his resignation this morning in Downing Street. He believed the result had undermined his authority and he wants a new prime minister in place by October.

The implications of the referendum are sweeping. At risk, the break-up of the UK.

Boris Johnson became a figurehead for the Leave campaign

Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU, but England and Wales did not. In Scotland, there will be demands for a second vote on independence. In Northern Ireland, Sinn Fein has already called for a vote on the Irish border.

This has been a seismic rebellion against the establishment.

It is a cry from thousands of people who felt angry and alienated. More than half the voters rejected all the pleadings from the president of the United States, the head of the IMF, and countless world leaders.

In the end, gut and instinct trumped all the arguments about economic turmoil and warnings of economic collapse.

In huge and unprecedented numbers the Labour vote broke for Leave.

For Europe, it is a political earthquake. No country has voted to leave the EU in its present form before. It will encourage other parties in other countries to hold similar referendums. The leader of the Far Right in France, Marine Le Pen, immediately welcomed the result.

Theresa May is a potential leadership candidate

Europe's leaders, however angry and frustrated, will have to recognise that this was a democratic decision.

In the short term, the priority for the government is to settle anxious financial markets by setting out a strategy for the days and weeks ahead.

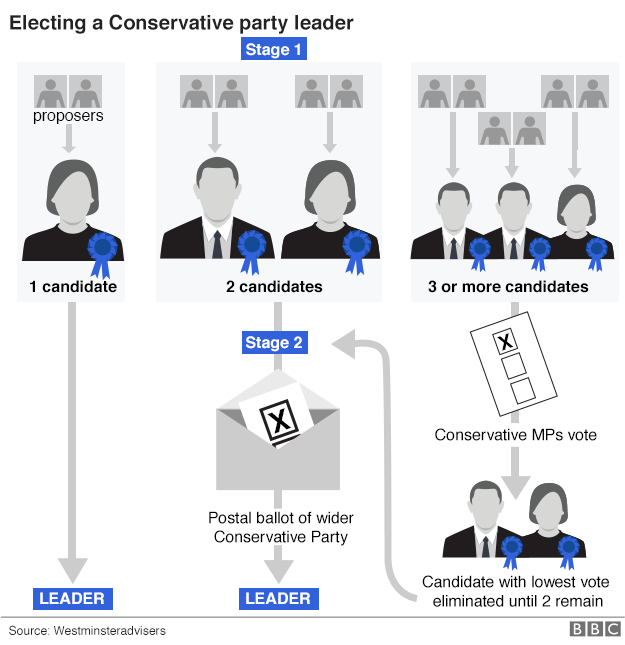

While the Conservative party prepares for a leadership election, no serious negotiations with the EU will start.

The prime minister has underlined that there will be no change for EU citizens living in this country or British citizens in the EU.

In the days and weeks ahead, the battle to succeed David Cameron will intensify.

Boris Johnson, as the standard-bearer of the Leave campaign, is hugely popular with the grassroots of the party.

George Osborne is very closely identified with the Remain campaign

George Osborne is closely identified with the Remain campaign and many in the party took issue with his dramatic warnings about the potential damage to the economy in the event of a vote to leave the EU.

Theresa May, the Home Secretary, could emerge as a strong candidate. During the campaign she was reserved while insisting that even if the UK had voted to remain there would have to be further reforms over freedom of movement.

Uniting the Conservative Party will not be easy.

Campaign scars

There are plenty of scars. At times, the campaign appeared as if it was a Tory civil war with political allies branding each other "liars".

David Cameron even denounced the "lies", external of his friend Michael Gove. The prime minister called on the public to ignore the Tory psychodrama but, at times, this was a bare-knuckle fight full of belief and passion and pent-up resentments.

At one point, former Prime Minister Sir John Major described the leaders of the Leave campaign as "the grave-diggers of our prosperity", external.

The party will remain badly divided over Europe. Some MPs will be very uneasy at the prospect of the Brexit camp taking over the leadership of the party. A majority of Tory MPs voted to remain in the EU.

In the short term there is likely to be a Cabinet reshuffle. Inevitably that will have to include those who led the Leave campaign and believe they have a democratic mandate.

But the tensions will not be easy to disguise. Many Tory MPs mistrust Boris Johnson. Some openly question whether he is prime minister material. Some fear him winning on a wave of grassroots support.

Committed Europeans among Conservative MPs may question their future in party.

The new leader must not only unite a bitterly divided party, but also successfully oversee complex and sensitive negotiations with the rest of Europe.

Michael Gove's relationship with David Cameron has been put under huge stress

Nothing has, so far, changed legally. Britain remains part of the EU until it formally withdraws.

The first decision is whether Britain will move swiftly to notify the European Union of the UK's intention to leave under Article 50.

Once that application has been registered, the clock starts ticking; the negotiation has to be settled within two years.

Many in the Leave campaign would prefer to start with informal talks. They do not want to be locked into a two-year timetable.

Some who voted for Leave believe it may be possible to win further concessions from Brussels over freedom of movement. Nothing like that will happen immediately.

Europe's leaders will want to send a signal that there will be no further deal for the UK. Their keenest instincts will be to prevent contagion, to deter other countries from holding their own referendums.

The future of the UK and of the EU is mired in uncertainty.

- Published19 June 2016