A less than United Kingdom

- Published

Leave campaigners are jubilant

The EU referendum has revealed an ancient, jagged fault line across the United Kingdom. It is a scar that has sliced through conventional politics and traditional social structures, and it is far from clear whether the kingdom can still call itself united.

The referendum was ostensibly about membership of the European Union. But voters took it to be asking a different question: what kind of country do you want Britain to be?

Yesterday seemed to offer a fork in the road: one path (Remain) promised it would lead to a modern world of opportunity based on interdependence; the other (Leave) was advertised as a route to an independent land that would respect tradition and heritage.

Which path people took depended on the prism through which they saw the world.

It has been striking to me how in one place almost everybody expressed genuine bewilderment that anyone would consider anything but a vote to leave, and in another neighbourhood they are quite baffled as to why people wouldn't be desperate to remain.

The maps of how people voted show that this was a victory for the countryside over the cities, particularly in England. London, Manchester, Bristol, Leicester, Leeds and Liverpool - for the most part, the metropolitan centres voted to remain. But the further from the big city centres one travels, the more emphatically people voted to leave.

City dwellers are generally more comfortable with globalisation and diversity. Country dwellers are more traditional in their outlook.

Successful cities are places in flux, constantly evolving to remain relevant in a rapidly changing world. A city without cranes is a city that is moribund.

But in market towns and rural villages, it is the opposite, with a focus on protecting heritage and celebrating history. It is a more conservative outlook that can see modern life as a threat, often nostalgic for a simpler, bucolic order.

Anti-London sentiment

At its most concentrated, this divide manifests itself as anti-London. There is a widespread view in the land beyond the M25 that the capital has been the driving force behind a globalising agenda that pays no regard to the customs and way of life of non-metropolitan Britain. London's overwhelming vote to remain will simply be seen as evidence of how out of touch it has become.

With Scotland voting overall to remain, and a similar picture in Northern Ireland, there will be powerful pressures upon the fabric of the UK. This country finds itself having to deal with an existential crisis.

London was out of step with much of the rest of England

As smaller nations with greater anxiety about isolation and irrelevance, Scotland and Northern Ireland saw the choice in a markedly different way to England. The Scots will be asking themselves some serious questions about how their best interests are now served. Similar conversations will take place in parts of Northern Ireland.

For many English voters, this was an opportunity to wave the flag of St George and restore a sense of national pride. Many resented what they saw as special treatment for other parts of the UK, particularly Scotland. In some respects, the vote for Brexit was a vote for English nationalism.

It was also a vote to stop foreigners and foreign ways changing the character of neighbourhoods and communities.

Anxiety about immigration is one manifestation of a broader fear of globalisation - an alien force that makes people uneasy or frightened, emerging unbidden and unwanted from the strange planet London.

The rural/urban divide is matched by a generational divide: young people largely supported Remain because they tend to be unafraid of modernity and embrace difference; older people largely supported Leave because they are more comfortable with what is familiar and are less at ease with change.

So it was that, for many, the seat of power became not the solution but the problem. London's "political class", you will hear it said, has been determined to force its will on the rest of the country, using every devilish trick at its disposal to make sure it gets its way.

Young people and those in Scotland were more inclined to support the European project

Before a vote was cast, a taxi driver in the north-west of England told me that Remain would win because the establishment would make sure it did. When I queried this view, he explained matter of factly that votes would be altered or the count fixed. To him, it was quite obvious.

He was not alone. In the days up to the referendum, Brexit supporters were advising each other to take a pen along to the polling station rather than use the pencil on offer when voting.

That belief in an establishment conspiracy will not go away with the result. The break with the EU will not be straightforward or swift. The disappointments of a messy Brexit, the concessions and compromises that real politics will demand, will test our system of governance.

Trust in politicians, already at very low levels, is likely to have been damaged still further by a campaign that saw both sides accuse the other of bare-faced lies, with institutions and authorities dismissed as corrupt, experts and public servants as biased.

The pillars of the British establishment have been damaged by the indiscriminate potshots of the disenchanted. Scepticism has given way to suspicion and cynicism. Our precious democracy has suffered injuries that will take years of careful work to repair.

The referendum has reminded us of a dangerous division that lies just beneath the surface of Britain.

The Leave share of the vote mapped

our browser does not support this interactive content. Results in detail are available here.

Industrial revolution

It is a volcanic gulf that has its origins in the furnaces of the Industrial Revolution. Traditional rural ways were crushed by the arrival of vast mechanised municipalities, and the legacy of that violent social upheaval lingers today.

In the century after 1750, Manchester was transformed from a market town of 18,000 inhabitants to a teeming metropolis of 300,000. It was a similar story in Bristol, Birmingham, Liverpool, Leeds and Newcastle.

Those sucked into the gravitational pull of the new manufacturing centres were forced to adapt to urban dominance, but such was the resentment that it lives on to this day.

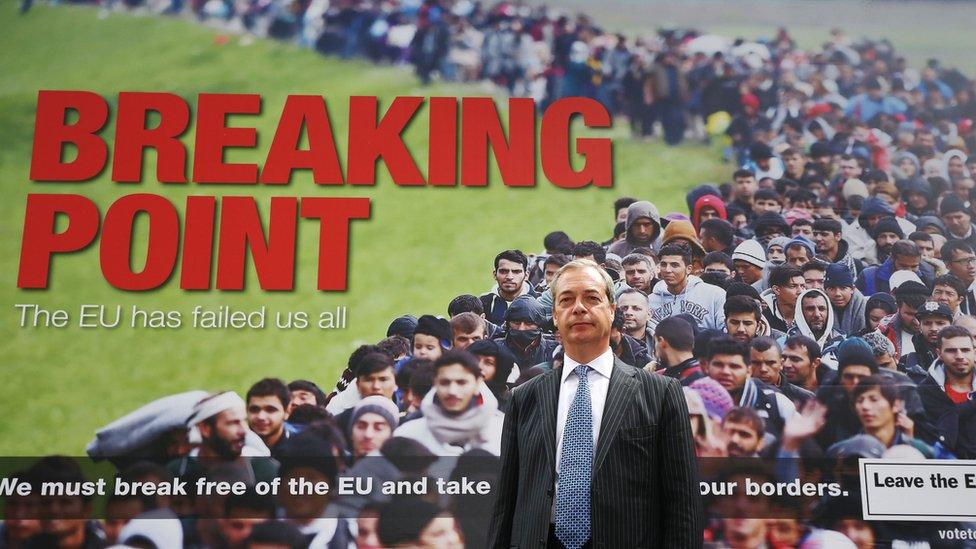

Nigel Farage and the Leave campaign successfully tapped into concern about levels of immigration

For the poor agricultural labourers marched from farm to factory, and for the rich landowners supplanted by ambitious industrialists, the new age of international trade was as horrifying as some regard the globalisation of today.

Then, as now, there was bewilderment at how anyone would willingly give up the certainties of age-old structures and customs for the risks of rapid social and economic change. Then, as now, equal bewilderment that anyone would willingly forgo the benefits of progress.

That is the ancient fault line that this referendum has exposed once again. The disillusioned of the left and the traditionalists of the right found common ground in opposing globalisation. The young, the well-educated and wealthy, those most resilient and optimistic, were far more willing to embrace the opportunities it offers.

It is a fault line across the UK, a scar that has never been properly treated. I do wonder now if it is more likely to tear apart than to be healed.

- Published19 June 2016