European Parliament: Guide to plenary sessions

- Published

A plenary sitting is the name given to a full session of the European Parliament, attended by all MEPs.

This is in contrast to the meetings of particular committees, or individual political groups.

Twelve full plenary sittings take place in Strasbourg every year, generally once a month with the exception of August, which is replaced by a secondary plenary sitting in September or October.

The sittings last from Monday afternoon until Thursday lunchtime.

There are also a small number of "mini-plenary" sittings that take place in Brussels each year on a Wednesday afternoon.

Every sitting starts with an official opening by the President of the European Parliament, Martin Schulz. This gives MEPs the chance to formally approve the agenda for the week and make any amendments.

Proposals to add a debate to the agenda have to be made to the President at least one hour before the sitting opens, and can be tabled by one of the Parliament's committees, one of its political groups, or a group of 40 MEPs.

In order to be formally added, an item must be approved by a simple majority - and can be done on a show of hands.

The session is then taken up with five main types of business:

Legislative debates

Once derided as a "rubber-stamping" chamber, the European Parliament's power to shape EU legislation increased significantly with the coming into force of the Lisbon Treaty, external in 2009.

The body is now a co-legislator with the Council of Ministers on the majority of EU laws.

For the remainder of EU legislation, the European Parliament has a formal consultative role.

MEPs have the power to scrutinise and shape EU legislation

Legislative debates usually open with a speech by the appointed "rapporteur", the MEP appointed by the relevant committee to draw up the Parliament's position on a proposed law.

A vote will have already been taken in committee, before going to the full parliament.

After this, the floor will normally be taken by spokespeople for other relevant committees, followed by the relevant EU Commissioner (it is the Commission that will have originally have proposed the legislation), and a representative of the EU Council of Ministers.

These interventions can be quite long, particularly if there has been a dispute between MEPs and national ministers over a piece of legislation.

The Council representative will generally be a minister from the country currently holding the EU's rotating presidency, external.

This is followed by spokespeople for the party groups, and then "backbench" MEPs - after which the Commission and Council get a chance to reply.

Often, however, it must be said that the plenary debates can consist mainly of the re-airing of political positions on the impact of legislation, rather than detailed scrutiny.

Most of this detailed scrutiny work will have already been done at committee stage, or in the private "trilogue meetings" held between MEPs, representatives of the Commission and national governments.

Voting sessions

MEPs use an electronic system to register their votes, but can also vote by simply raising their hands

These take place before lunch on the Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday of plenary weeks, normally lasting around an hour.

Unlike at Westminster, votes are often not taken directly after the relevant debate - but later in the day, or during the following day's session.

On occasions, MEPs can even vote on proposals debated during a previous plenary sitting.

As well as voting on legislation and resolutions that have been the subject of a full plenary debate, MEPs also vote on uncontroversial or procedural matters that come direct from the relevant committee.

Votes are taken on every amendment, and MEPs may submit oral amendments at the last minute.

Voting is either undertaken on a show of hands or, when the result of a show of hands is unclear or it has been requested by a political group, by electronic vote with or without a roll-call.

Roll-call votes are often requested by political groups who want to force the MEPs of other groups to leave a written, publicly-available record of where they stood on a controversial law or amendment.

This is what happened in July 2015, when MEPs slogged through a long round of button-pushing to vote on a raft of amendments to their advisory resolution, external on the controversial TTIP EU-US trade deal.

The vote was meant to have taken place at the previous month's sitting, but was controversially put back by Parliament President Martin Schulz, who claimed, external it was because too many amendments and requests for roll-call votes had been tabled.

Following the votes, MEPs have the chance to explain why they voted in a particular way.

General debates

These are usually in the form of a statement by a representative from the Council and/or Commission, followed by a debate by MEPs.

They can also take place following an oral question to either the Commission or the Council that has been tabled by a committee, a political group or a group of 40 MEPs.

Most result in a resolution being tabled, allowing the Parliament to set out its view on a particular issue.

Following reforms to the Parliament's rules in 2002, "extraordinary" debates can be added after the official adoption of the agenda on the Monday, in response to a breaking event.

Such debates can be proposed by the President, after consulting the political group leaders.

Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager making a statement to MEPs during a plenary sitting in Strasbourg

Human rights debates

These take place during the full monthly Strasbourg sessions, and are now normally scheduled for the Thursday morning sittings.

Three areas of alleged human rights abuses are debated, followed by a vote on resolutions.

All member states are legally bound to respect the rights enshrined in the EU's Charter of Fundamental Rights, external and the EU has a treaty commitment to promote human rights in its "relations with the wider world".

The Parliament has a treaty role to monitor how these commitments are being implemented.

This means that MEPs can end up discussing topics as diverse as abortion rights in Paraguay, external or traditional land tenure rights, external for ethnic groups in Tanzania, sometimes prompting accusations from some in the chamber that the Parliament is acting in a "busybody" or culturally imperialist manner.

Often, the debates end up being about what kind of trade relationship the EU should have with countries where there are alleged human rights abuses.

Formal sittings

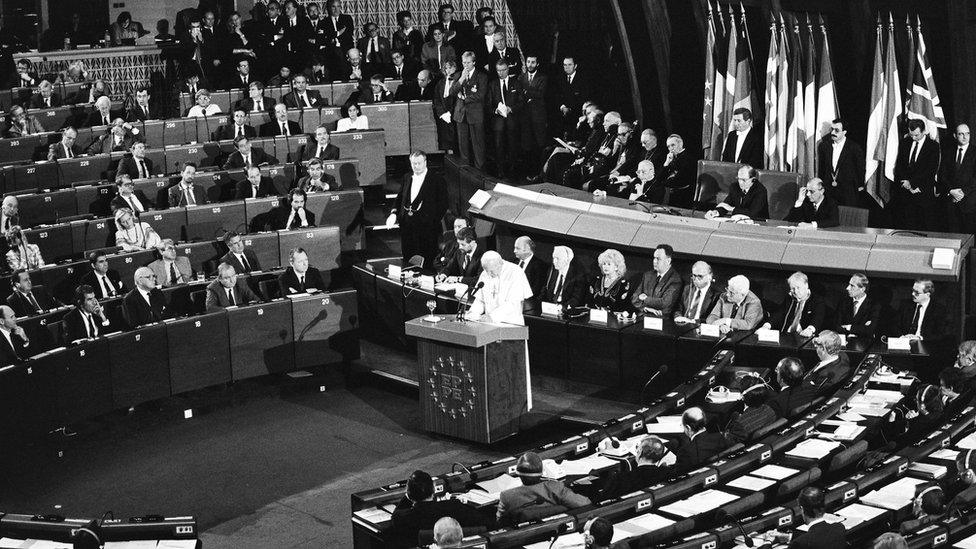

The Parliament receives a number of high-profile visitors to speak during plenary sittings, including heads of state from both EU and non-EU countries, as well as various spiritual and religious leaders, external.

Normally, a special lecturn is placed in the middle of the hemicycle, from which the speaker can address the entire chamber.

Formal sittings normally just consist of the speech, with MEPs not allowed to intervene or make points of order.

Pope John Paul II is just one of a number of high-profile figures who have made speeches in the European Parliament

For the most part, the content of the speeches is relatively uncontroversial - but big-name figures can sometimes use the platform to make more contentious political points.

In November 2014, Pope Francis made headlines with his call for EU nations to find a "united response" to the migration crisis in the Mediterranean, and his description of Europe as "elderly and haggard".

Formal sittings in the Parliament do not always go quite to plan.

The first pontiff to visit the chamber, John Paul II, was heckled, external as the "antichrist" by the late DUP leader Ian Paisley.