Fires, floods and mice: What it's like to work in a crumbling Parliament

- Published

The Palace of Westminster's famous towers, gilt and gargoyles exude grandeur. But descending into the basement which runs underneath the Houses of Parliament inspires a different kind of awe - alarm and anxiety.

To go on a tour of the cavernous corridors below the building is to enter a seemingly never-ending network of claustrophobic passageways lined with huge tangles of protruding wires and pipes, taped up here and there, leaking, hot to the touch.

Faults go unmended because the pipes are so entwined they cannot be safely dismantled, and boiling steam rushes through ancient plumbing all day and night because engineers are afraid if they switched it off they would not be able to get it back on again.

The overall impression is of a temporary fix ready to give way to flood or fire at any moment.

The team charged with keeping the whole thing ticking over says the basement gives the clearest image of how precarious the situation is.

But increasingly the sticking plasters fall off and the failing fabric of the building gives way, making it difficult for the people who work there to do their jobs.

What's it like inside Parliament?

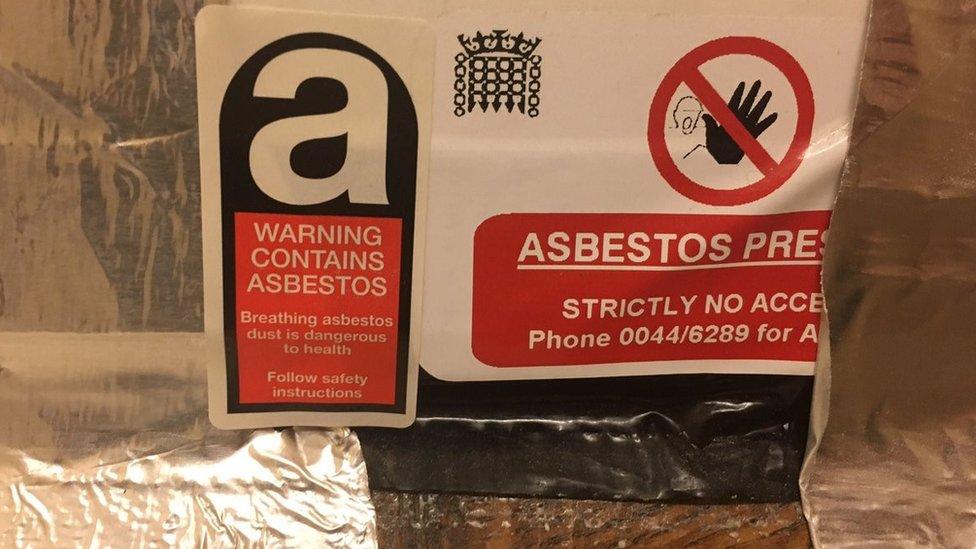

One assistant to a Conservative MP told the BBC that all the staff in her office on the lower-ground floor of the Palace had to relocate twice while asbestos was removed, and again after a pipe burst in the corridor.

On one occasion, she was working in her office when a light fitting fell from the ceiling on to her desk.

Staff have had to move offices repeatedly due to asbestos

"They've taken the approach of just putting plasters on problems rather than overhauling it," she says, "so overall it's just a bit dodgy."

"The walkway to the car park is usually so flooded underneath that the floor panels bounce around and your shoes get soaked."

A Labour researcher recalled an occasion a few years ago when the toilets above Exeter MP Ben Bradshaw's office "leaked through and dripped onto papers, leaving horrid smells".

The sight of mice running around is so commonplace that several parliamentary workers only mentioned it in passing, saying, "oh yeah, we've got loads" or "the place is riddled with them".

A parliamentary spokesman said: "Providing a physical working environment that is as safe as we can possibly make it is an absolute priority."

Overloaded and unsafe wiring carries the constant risk of fire

The Labour MP Meg Hillier has investigated options for the restoration of Parliament as chair of the Public Accounts Committee, but also has personal experience of doing battle with the dilapidated surroundings.

She told the BBC of the "hole in the carpet which you have to remember where it is otherwise your foot goes through it".

She added: "The plugs in my office buzz and spark - I take extra care to switch them all off before I leave because I'm terrified of a fire starting in there."

The head of engineering on the estate, Andy Piper, says that if a fire were to start everyone could be evacuated, but at present he is not confident the building could be saved as it would not be safe for firefighters to enter.

Warnings from history

It's estimated that 60 small fires have started on the estate over the past 10 years, and 24 fire inspectors patrol the grounds on rotation.

Caroline Shenton, author of several books on the history of the building, points out that concerns raised by MPs and architects in the 1830s about the condition of the accommodation went unanswered.

Historians see parallels with the warnings that preceded the 1834 fire

In 1834, a massive fire destroyed both Houses of Parliament and other buildings on the site.

"I do see a parallel because there had been years of attempts to change the accommodation, and the squabbles were exactly the same - over symbolism and expense," she says.

Alexandra Meakin, a former clerk in Parliament and research associate at the University of Sheffield, summarises the situation as "desperate".

She points out that most of the electricity and plumbing was originally put in after World War II and went out of date in the 1960s and 70s.

Why has nothing happened?

It's now been over a year since a specially convened committee recommended a complete relocation of all staff from the Palace of Westminster, external to allow major restoration works to take place.

Buckets catch leaks in the peers' Not Content lobby

"Major" does not do justice to the scale of the programme - the head engineer at Parliament told the BBC there wasn't any comparable project in the UK.

"People liken it to restoring a cathedral or a stately home, but that doesn't come close - and those places would not have hundreds of people working there, as well as being the seat of government."

Even if the government were to give the green light tomorrow, it would take several years just to move people out and get reconstruction started. So why wait?

There are some who believe it's essential for MPs to remain in place at all costs, and would prefer repairs to take place around them.

As Conservative Sir Edward Leigh put it earlier this year: "This is not an office block. If it were I would agree we should move out, but it is not.

"It is the centre of the nation and the nation should keep its debating chamber in this building."

Can the government find time to restore Parliament while it debates Brexit?

Others are of the view that there are better uses for £3.6bn - especially with the social housing shortage in the spotlight.

Another Conservative MP, Shailesh Vara, summarised it thus: "When we are writing to our constituents and saying that they cannot have an additional few pounds for whatever they are seeking money for, do we really want to go to the public and say that, nevertheless, we want to spend billions of pounds on our place of work?"

Meg Hillier doesn't buy this argument, reasoning: "The public aren't going to have much confidence in us if we can't keep our own house from falling down."

What next?

From a procedural perspective, a motion approving the restoration has to be brought forward and passed in government time.

There has been speculation ministers are shying away from bringing it forward as they face the not-insignificant task of legislating for Brexit.

Former Parliamentary clerk Alexandra Meakin says: "Given the cost of the programme, and the fear of media hostility - particularly in the wake of the Big Ben furore - there is very little incentive for the government to hold the debate."

A spokesman for the leader of the Commons, Andrea Leadsom denied this, telling the BBC: "Discussions are ongoing within Parliament and efforts to arrive at a consensus continue."

As Parliament resumes after recess, this could be the session in which MPs finally take action.

But in the meantime, as one member of House services put it: "We are prisoners of the building's historic and iconic significance."

- Published16 January 2017

- Published8 September 2016

- Published18 June 2015