Can Theresa May's Travolta/Micawber strategy last?

- Published

MPs and Peers should make the most of their summer holidays; when they return to Westminster on Tuesday, 4 September the tensions will be rising because critical Brexit decisions loom, and the hung Parliament of 2017 is becoming ever more precariously balanced.

There are now at least three Conservative parties and three Labour parties - and the widening cracks in party loyalties suggest that the fragmentation is only just beginning.

Far from unifying the Conservatives, Theresa May's Chequers deal on the shape of Brexit seems to have deepened her party divisions.

Remainers and hard Brexiteers alike seem alienated, openly distrustful of their leader and increasingly organised and cohesive parties within a party. And the party mainstream is feeling battered and uncertain. They face a bruising party conference in September and a long ear-bashing from their local activists over the summer.

On the Labour side the Brexit strains are different - but equally painful.

There are perhaps four or five really hardcore Leavers, and a somewhat larger group of hardcore Remainers.

But there are also a fair number of Labour MPs with heavily Leave seats, like Caroline Flint in Don Valley or Gareth Snell in Stoke Central, who are very wary of Labour taking a position that could be interpreted as disrespectful of the 2016 EU referendum verdict.

As a matter of sheer electoral survival, they will be very resistant to any Brexit strategy involving continued free movement (EEA membership, for example). And all these tensions play into parliamentary Labour's increasingly painful ideological strains.

So one of the main drivers for both party leaderships is the need to keep their respective shows on the road - to maintain party unity across what increasingly seems an unbridgeable Brexit divide.

Hence Theresa May's constant micro-compromises and Jeremy Corbyn's studied vagueness.

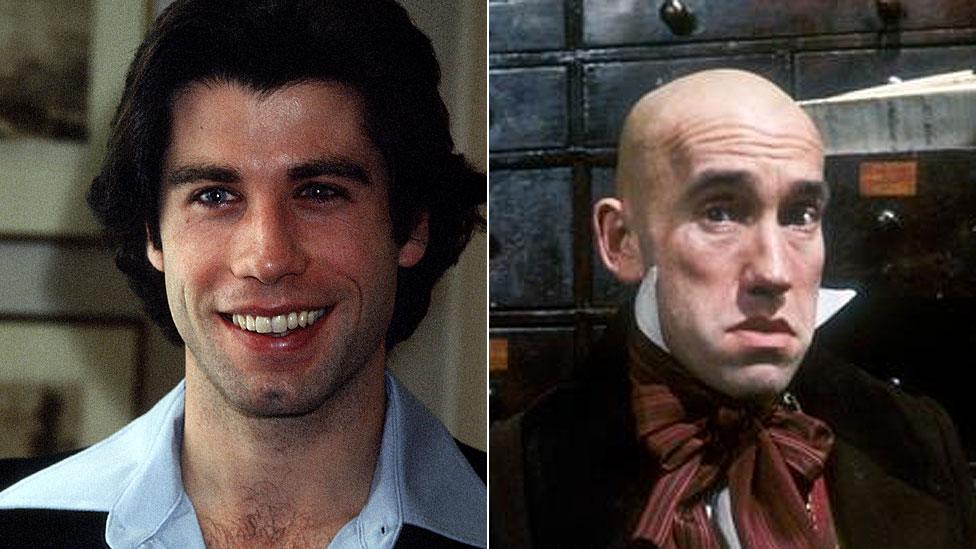

John Travolta strutted to the Bee Gees' Staying Alive in 1977's Saturday Night Fever. Dickens character Wilkins Micawber, played by Simon Callow in a 1996 BBC production of David Copperfield, hoped something would turn up

The trouble is that actual decisions loom, and it may well be that there is no Commons majority for any kind of Brexit, from the hardest boiled, to the most softly poached.

It is quite possible to imagine MPs rejecting whatever deal Theresa May brings back from the Brexit talks - each option would produce its own clutch of refuseniks, who regarded it as too hard, too soft, too close to the EU or too far away. If Anna Soubry likes the deal, can Jacob Rees Mogg possibly accept it?

Watching from the sidelines will be a Labour Party hoping to leverage Tory divisions into an early election, which would allow them to capitalise on government disarray.

Remember - the government very nearly lost a key vote on the Taxation (Cross Border) Trade Bill in mid-July, when its bacon was saved by the absence of two Lib Dems and the votes of four Labour MPs.

In a situation where the Conservative Remainers/soft Brexiteers held firm, Labour managed to keep its Brexiteers onside (perhaps on the argument that they could bring the government down) and no-one had wandered off to some power dinner, the government could easily lose a critical vote.

Now, to be sure, none of those conditions would be easy to meet; would all the Tory rebels really be prepared to risk the fall of the government and an early election, not to mention their own de-selection? Would the Labour Brexiteers be persuadable on this of all issues? And might the government find a way to buy off one of the smaller parties?

But if the government did lose, what then? Could the prime minister possibly survive the defeat of her personally chosen negotiated and administered Brexit strategy?

If not, how could a Tory leadership contest possibly be held during the final few negotiating weeks before Brexit Day?

It is this thought which spawns fanciful talk of "governments of national unity" ("I'm a GNU, how d'you do?") or new centre parties, or some other magic solution which makes the parliamentary arithmetic shut up and go away.

I suspect the most likely answer, as at several stages before, is to delay.

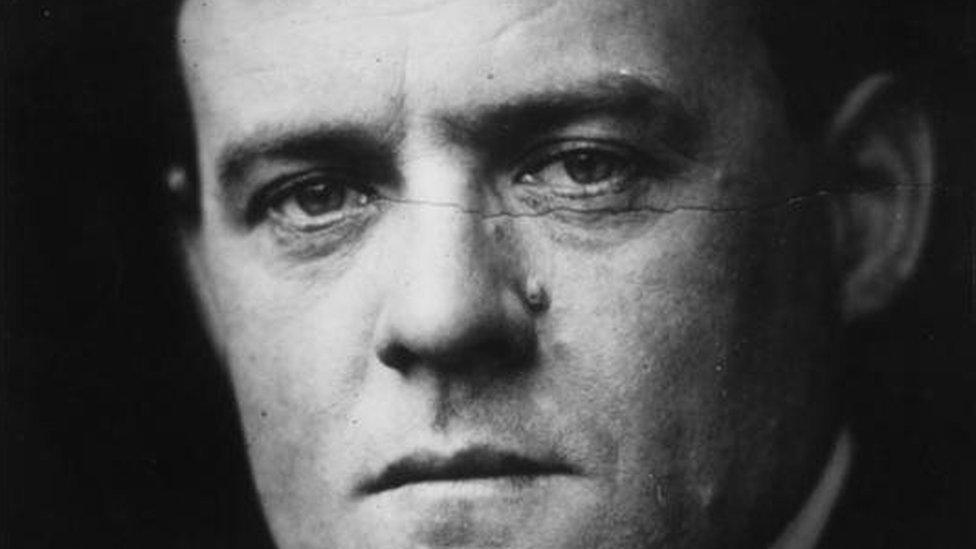

Poet Hilaire Belloc is known for a cautionary tale of a boy who ran away from nurse and was eaten by a lion

Postpone the crucial talks with EU leaders from October to December, and perhaps beyond.

Swallow the odd legislative defeat on Brexit, and plot to reverse it in future legislation.

Ultimately, maybe appeal to the EU for an extension of the Article 50 negotiating deadline, and keep playing for more time.

Of course, that ultimate option asking for an extended Article 50 period would require legislation, since Brexit Day is set in law as 31 March, 2019 - and that would provide an obvious opportunity for Brexiteer rebels to strike - but that just returns them to the same dilemma; do they want to bring down the government and precipitate an election with their party in bits?

Maybe the underlying strategy for the PM is to march her warring factions right up to the cliff-edge, and get them to take a long hard look at the waves dashing against the rocks below.

Force them to face the political consequences of disunity, and hope she can scare enough of them back into line, to get her deal through Parliament.

This is the moment at which the current Travolta-Micawber strategy ("Stayin' alive and waiting for something to turn up….") morphs into a Hilaire Belloc strategy - "always keep a-hold of nurse, for fear of finding something worse."