Parliament: what does the contempt challenge mean?

- Published

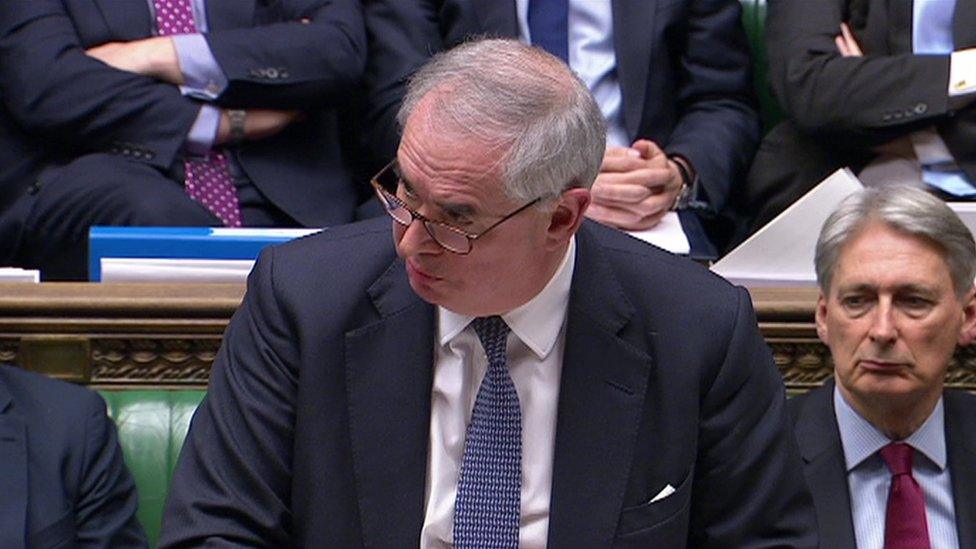

The Attorney General spent some hours at the dispatch box, outlining his legal advice to the Cabinet

What will today's Commons motion to hold "ministers" in contempt actually mean, if MPs approve it?

It is so long since such a thing has happened, that nobody really knows.

But anyone expecting to see Geoffrey Cox or David Lidington doing a perp walk in leg irons should not hold their breath.

The motion before the House does not name individuals, or call for any specific punishment, so suggestions that it might result in the suspension of a minister or ministers from the Commons, during next week's "Meaningful Vote" look overblown.

The complaint in the motion is that "ministers" failed to comply with the requirements of the motion passed by MPs on 13 November, to publish the Attorney-General's full legal advice on the EU Withdrawal Agreement and the accompanying framework for a future relationship - and the whole thing might be defused if the government simply disgorged the documents.

Just passing the motion on today's Order Paper does not mean anyone is referred to the Privileges Committee for punishment - that would require some follow up by the authors of the motion or, just conceivably, the Speaker.

The key issue is how the government responds if the motion is passed.

Particularly if they still refuse to comply.

At that point, Sir Keir Starmer and the cross party allies, who joined him in the original contempt of Parliament complaint, could up the ante and demand specific sanctions against individuals.

The government amendment to the motion refers the issue of MPs' right to demand government papers to the Privileges Committee - to determine whether the statement by the Attorney General and the various briefings and documents he has provided, external constitute an adequate response to the 13 November demand for publication.

But this cuts across a live inquiry by the Public Administration Committee, and the normal territory of the Procedure Committee, so there might be a bit of a turf war over who should be deciding that question.

Historically Parliament has always had the right to demand papers - the cryptic-looking "motions for unopposed return" which crop up on the Order Paper from time to time, are a device to bring papers into the orbit of Parliament, where they are covered by Privilege - so, for example, the papers around the Hillsborough Inquiry, which might have caused all kinds of legal problems if published without privilege, were protected by this means.

A couple of hundred years ago, MPs demanded the King reveal the names of the advisors who had persuaded him to impose the "Stamp" - the tax on tea, which provoked the American War of Independence….

So it's simply not true to say that Parliament has never made these demands.

And if useful anything emerges from this imbroglio, it may be that it establishes clear ground rules on MPs' access to documents.