Plans for interim Parliament take shape

- Published

The Palace of Westminster, the home of Parliament, is in danger of going the way of Notre-Dame.

The electrical system is iffy, the pipes leak, the stonework is crumbling and the roofs need replacement.

It is simply not possible to do the necessary work with MPs and peers still working in the building - the deterioration is now happening faster than can be remedied at weekends and during holidays.

But before MPs and peers move out of their Victorian home, there has to be somewhere for them to go; the plans unveiled today are a detailed vision of their proposed destination, complete with a stand-in Commons chamber, a new atrium, a terrace, and all the required committee rooms, voting lobbies and the rest, all fenced in by a three-metre fence in Whitehall, to ensure security.

The brief for the team of architects behind the plan was to weave together a complex of 18th, 19th, 20th and 21st Century buildings into a new parliamentary campus - and their revamp turns the disparate collection of former government offices, private homes and the world's first purpose-built police headquarters into a coherent, even elegant whole.

The plan is to demolish most of Richmond House, the office building which used to house the Department of Health, to make way for a new Commons chamber housed in a new six-floor building.

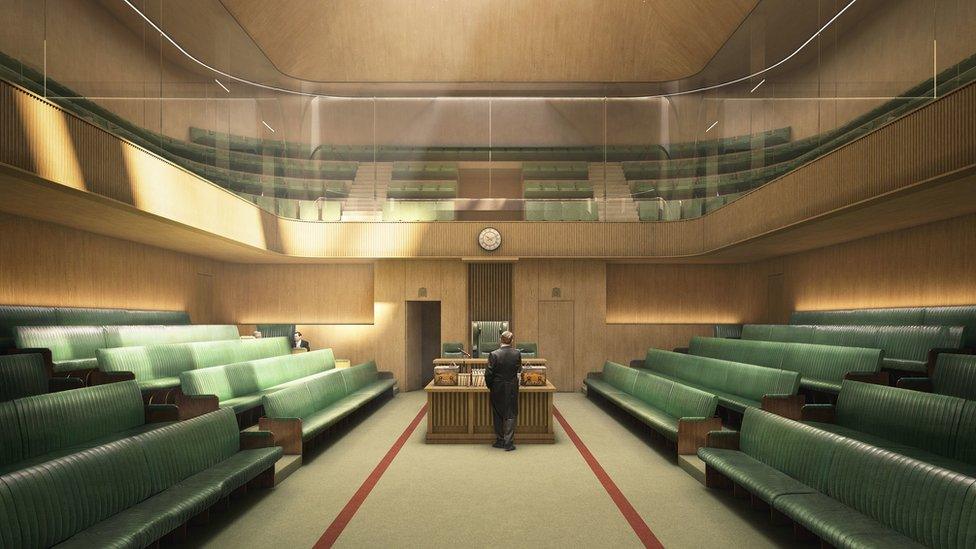

The new chamber would have the same configuration as the original, but with better accessibility for disabled people and wheelchair users. The design would be far less elaborate than the "Neon Gothic" styling of the chamber rebuild after the bomb damage of the Second Wold War.

The public gallery would be a little smaller, but the design would, it is intended, provide greater visibility for visitors and the press. There would also be a terrace overlooking Whitehall.

The adversarial design of the current chamber would be maintained

There have been some suggestions that the relocation would provide an opportunity to shift to an electronic voting system, rather than continue to have MPs register their votes by trooping through the division lobbies, in a process that takes around twenty minutes for each vote; the temporary chamber will be provided with Aye and No lobbies, so the current method will continue unless MPs decide to change it.

The fate of Richmond House is one of the potential problems with the plan - the building is Grade II listed, largely because of Sir William Whitfield's striking façade and the cathedral-like entrance hall behind it.

These features would be retained and will become the main entrance to the Commons' temporary home, and the backdrop to a new Central Lobby - a space where MPs can meet their constituents. The argument is that the floor heights in the existing building make it more difficult, expensive and awkward to fit a new chamber into the current building, but Historic England has yet to grant consent to alter the building, and this could yet become a stumbling block.

Inside the campus, Cannon Row, currently a closed-off street running alongside Whitehall, will become a major internal thoroughfare, through which the denizens of the parliamentary estate will reach the Commons chamber, while other internal alleyways and courtyards would be opened up and refurbished.

The Grade II listed Norman Shaw North building, originally built as the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police - the "Victorian Scotland Yard" - will be refurbished, and its central courtyard roofed over, to provide a new social and catering space, replacing some of those that will be closed when the main building is revamped. Much of the redesign involved liberating existing spaces from a clutter of portable buildings and storage, so that people will be able to move around the new campus easily.

To maintain security - and remembering that Parliament was the target of a terrorist attack in 2016 - there will be a three-metre fence along the Whitehall frontage, removable for state occasions, including the Remembrance Day ceremonials at the Cenotaph, just outside the new main entrance. And there will be a "security pavilion" at the main entrance, to screen visitors before they move into the main building.

All this won't be cheap, with the total cost expected to come in at somewhere between £1.4 and 1.6 billion - and the work has to be completed before MPs can move out of their Victorian home across the road.

Meanwhile, in a separate project, peers will be relocated to the nearby QEII Conference Centre, which will also need extensive modification to house them and a temporary House of Lords chamber. The aim is to be able to move MPs and peers out of the main building by 2025, so that the £4bn restoration and renewal programme can begin - with a triumphant return to their ancient home pencilled in for, perhaps, 2033.

Today, the bill to set up the structure which will oversee the whole giant project was put before Parliament. It includes an Olympic-style delivery authority, which will report to a sponsor body on which politicians will be in a minority, with a non-politician in the chair.

MPs are expected to consider and vote on the business case for the whole exercise in 2021. This will be the detailed plan for the project, and its costs will then be monitored by an estimates committee.

And thus, the hope is, the cost of revamping one of the three or four most recognisable buildings in the world will be kept firmly under control.

- Published1 February 2018