Boris Johnson: Can new PM deliver in the Commons?

- Published

There was a moment in Thursday's Commons sitting that crystallised the approach of Boris Johnson's new government.

Labour MP Gareth Snell asked the new Leader of the House, Jacob Rees-Mogg, when the government was going to bring back the Trade Bill for MPs to consider.

Now, the Trade Bill is one of a number of measures loaded with anti-Brexit booby traps by peers - in this case an amendment calling for Britain to remain in a customs union with the EU, something Remainer MPs might uphold in the Commons.

Mr Rees-Mogg dealt with that suggestion with a brusque nine words: "Why on earth would anybody want to do that?"

No faffing around with talk about "in due course", or "when the moment is ripe".

My point is that this is a government on a war footing. In Mr Johnson's words, Brexit is "do or die" and so there is no room for niceties. Battle is joined.

Flights of oratory

Much of the battle will be fought out in the Commons chamber.

Already, pro-Remain MPs, looking at the visible intent of the new administration, are talking about having to bring their plans to block a no-deal exit forward to the first week of September.

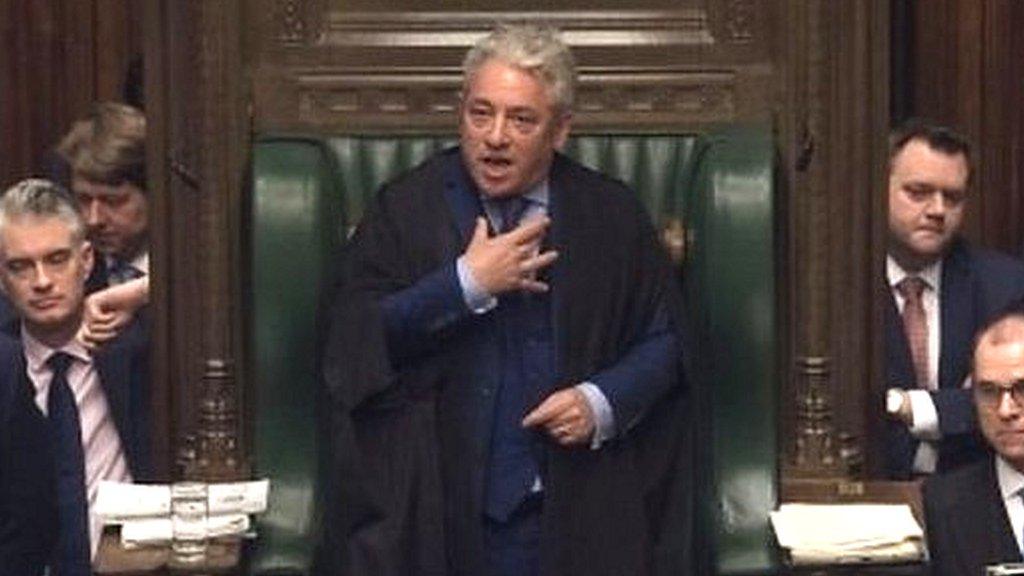

The exact nature of their plan is yet to be revealed, but some "Letwin-esque" move to seize control of the parliamentary agenda and legislate against no deal is clearly on the cards - even if the procedural assistance of Speaker John Bercow may be required to bring it to the wicket.

The ensuing battles will be fought out on two levels: the arguments in the chamber and the appeals to the wider public beyond it.

And this is where the parliamentary style of the new prime minister comes into play. Mr Johnson's oratory is unique; flights of grandiloquence, high-energy gestures, thumps on the dispatch box, swivelling round to address the troops directly.

First, the contrast with Theresa May matters a lot - there's verve and relish, rather than a sense of endurance and dour determination.

Even a hard Remainer ex-minister I spoke to after Mr Johnson's statement on Thursday said it had put a smile on his face for the first time in months. The ferocity of the onslaught on Jeremy Corbyn delighted him.

Advantage PM

The Labour leader is facing a completely different adversary than before

Expect Mr Johnson to keep up the attack, because he'd love to go into an election with his ascendency over his rival firmly established.

Mr Corbyn, meanwhile, will need to find a way to tackle a completely different and utterly unpredictable adversary - because, while his appeal does not rest on his parliamentary performances, he will not want to be trounced on a weekly basis.

But while the structure of PMQs gives a prime minister considerable advantages - only the leader of the opposition gets more than two questions to press their point and the PM always gets the last word - they can be attacked from any angle, and damaged by some entirely unexpected question.

Before his marathon debut statement on Thursday, Mr Johnson had seldom really shone in the Commons, either as a backbencher or in his short spell as foreign secretary (and the debacle over his remarks about Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe still hangs over him).

It is worth noting that that particular mistake occurred under questioning by the Foreign Affairs Committee, and Prime Minister Johnson will face much more sustained questioning from the Liaison Committee, which is composed of select committee chairs, so that could become another dangerous testing ground.

One clue to how he will shape up can be found in his performances in Mayoral Question Time during his two terms as mayor of Greater London.

Short fuse

As Mayor of London, Boris Johnson was frequently goaded by Labour opponents

The Labour Assembly Member - and former MP - Andrew Dismore, learned how to get under his skin and did so repeatedly and mercilessly.

It so enraged the future prime minister that he was goaded into telling him to "get stuffed" and later advising him where to stick a paper he was referring to, to the delighted "ooohs" of his political opponents.

The lesson is that Mr Johnson has a short fuse, and opposition MPs will seek to light it.

Mr Dismore told me the prime minister would use his wit to good effect, but he didn't like being the butt of other people's jokes or being reminded of unkept election pledges. But he thinks the key weakness is that "he just doesn't do detail".

Beyond the cut and thrust of PMQs there is a wider question about the Johnson style. The quick-fire delivery, the ideas flying about like popcorn from a pan, the exotic, ornate, language may all amuse the House, but they do not command it.

And the style is not good for all occasions. Sometimes a prime minister needs force of argument and gravitas, rather than some insouciant quip.

Angela Smith, the Labour peer who was Gordon Brown's parliamentary aide when he became prime minister, told me that the Commons liked answers to be respectful, at least most of the time, and that getting through the best part of an hour of PMQs could not be done on wit alone.

The PM's close ally, James Cleverly, believes he can adapt, and that he is capable of striking the right tone on difficult occasions.

But in the cauldron of PMQs the price of a misplaced joke or a show of temper will be much higher than ever it was in the chamber of the Greater London Assembly.

- Published28 October 2019

- Published11 July 2019

- Published3 September 2019