Supreme Court: What will MPs do when Parliament resumes?

- Published

John Bercow will be back in the Speaker's chair from 11.30 BST

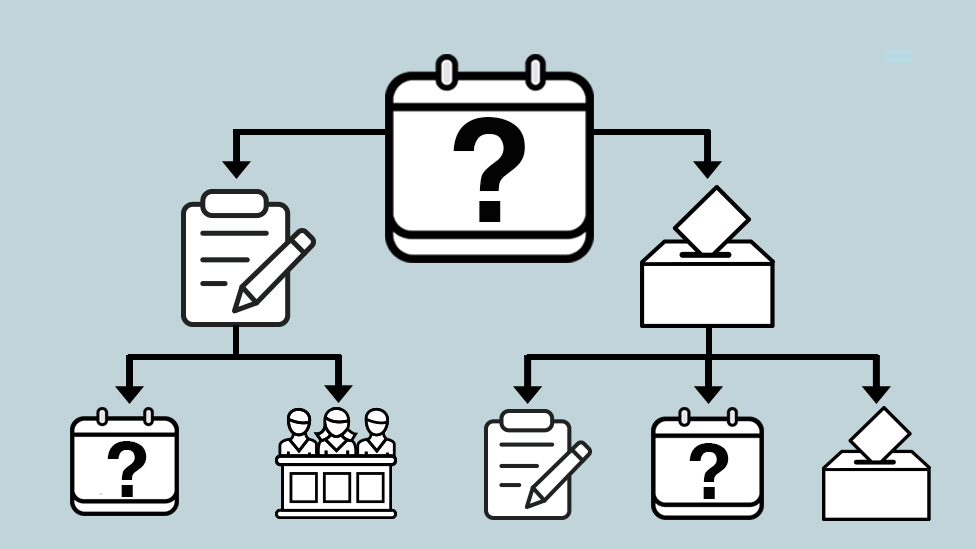

When Parliament "resumes" tomorrow, what will MPs do?

The Speaker has made it clear that there will be full scope for urgent questions, ministerial statements and applications for emergency debates, but will that include a no confidence motion against the government?

On the one hand, the rebuff delivered by the Supreme Court looks like the perfect fuel for a new assault on the government; on the other hand, would it simply get in the way of attempts to prevent a no-deal Brexit?

For the cross-party alliance of Remainers which pushed the Benn Act through Parliament a few weeks ago, the priority remains to stop a no-deal exit.

That means that they will want to hold the prime minister to the bill's requirement to seek an extension to Britain's EU membership, if he has failed to come up with a new exit deal - despite his comment that he would rather die in a ditch.

Parliament will now be there to hold his feet to the fire. Perhaps he would rather be no-confidenced than sign a letter requesting a further postponement of Brexit.

On the principle that the Queen's government must be carried on, a prime minister cannot resign until they have advised Her Majesty to send for a named successor - and who would that be?

Jeremy Corbyn, as Leader of the Opposition, would surely have first dibs, but could he command the Commons majority necessary to form a government?

If not, then the hunt would be on for some cross-party figure who could muster the support of Labour MPs, Conservative rebels and most of the smaller parties and the disparate collection of independents.

Does such a snark-like leader even exist? All kinds of names have been touted - Ken Clarke, Hilary Benn, Dominic Grieve and Margaret Beckett - but, like Lewis Carroll's elusive creature, their appeal might fade into nothingness on closer inspection.

That would leave the Commons flailing around while the clock ticked down to Brexit day. This is why many on the opposition side of the Commons say bringing a no-confidence vote would be a huge tactical error.

They want a Brexit postponement nailed down first. But the pressure to bring down a prime minister wounded by the Supreme Court Justices is huge - and a hesitation in striking, after all their calls for Boris Johnson to go, would not be easy to explain.

Maybe that is one of the attractions, for the PM's opponents, of launching an investigation into his conduct, and possible contempt of Parliament, which would unfold over the longer term.

Another Brexit point; since the prorogation did not occur, the 2017 session of Parliament is still under way.

And under Speaker Bercow's earlier ruling, the government cannot have a third go at seeking to win MPs' approval for Theresa May's withdrawal agreement in this session.

This matters because one compromise option being mooted by some Labour MPs was to hold another "meaningful vote" on the Theresa May deal.

That cannot now happen, unless Mr Speaker could be persuaded that new assurances and legislation around it made it a substantially different deal.

As the session is still going though, all the bills thought to have fallen in the unlawful prorogation now bounce back into parliamentary life.

These include several measures from Mrs May's Brexit strategy (the Trade Bill, for example) that had languished in limbo for many months because they seemed certain to be amended in ways embarrassing to ministers.

Essential is that they are holdovers from a failed Brexit strategy, so there is little incentive for the government to bring them back before MPs or peers.

The one that might be fed back into the system is the Domestic Abuse Bill, which was due for a Second Reading Debate when the "prorogation" came.

There was quite a backlash about its demise, and the government committed to bring it back in their next legislative program.

- Published13 July 2020

- Published3 September 2019