Universities take a knock post-Brexit

- Published

Research bids have been hit, says the vice-chancellor of Sheffield Hallam University, Chris Husbands

European academic bodies are pulling back from research collaboration with UK academics, amid post-Brexit uncertainty about the future of UK higher education.

While post-Brexit Britain might remain inside the European research funding system, academics in other countries are nervous about collaborating with UK institutions.

UK-based academics are being asked to withdraw their applications for future funding by European partners.

BBC Newsnight is aware of concerns raised by academics at Bristol, Oxford, Cambridge, Exeter and Durham.

Chris Husbands, the vice-chancellor at Sheffield Hallam, says that his researchers are already seeing significant effects.

He told Newsnight: "Since the referendum result, of the 12 projects that we have people working on for submission for an end-of-August deadline, on four of those projects researchers in other European countries have said that they no longer feel that the UK should be a partner because they don't have confidence in what the future is going to hold."

The higher education sector was broadly in favour of a Remain vote in the referendum

He added: "Leaving the EU doesn't necessarily mean being outside the European research network. Norway, Switzerland - they are part of the European research network [despite being out of the EU]. And it may be that there's where we end up.

"But it's not where we are now and in that uncertainty people are making decisions about what might happen - and like all people planning for the future, they're planning on a worst-case scenario."

Three other vice-chancellors, who have asked to remain anonymous, have confirmed similar problems for their researchers.

They also say they are fielding calls from prospective future EU students about their access to student loans and their immigration status.

They also report that staff members and prospective staff members have notified them of their decisions to seek work elsewhere in the EU.

At the moment, the UK and its universities remain full members of the EU. Jo Johnson, the science minister, has asked for academics to report any examples of British academics being discriminated against.

But academics in other countries are quite open that they are concerned about working with people who may become ineligible for future grants. Others have told Newsnight they fear the EU might not fund research in a country on the cusp of leaving the EU.

Stephan Koppe, an academic at University College Dublin, tweeted that he did not invite British academics to join with him recently, even before the referendum, because he feared the outcome.

The higher education sector was fiercely in favour of remaining in the EU.

Across the whole sector, more than 125,000 non-UK EU students are currently studying at UK universities, making up 5% of the entire student body.

At the London School of Economics, they make up 18% of the student body. The EU is also estimated to contribute about 15 per cent of the higher education workforce.

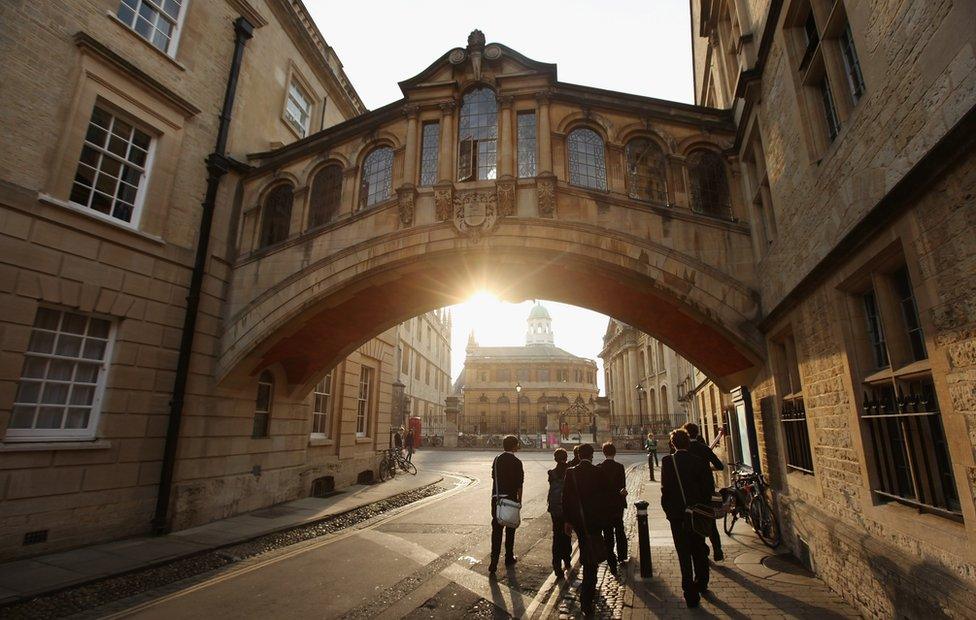

Academics at Oxford University have also expressed concerns about the impact of the Brexit vote

UK universities also won more than £800m in funding from the EU for research.

The critical concern for most vice-chancellors is research collaboration. In any given field where a researcher is hoping to make novel progress, there may only be a few experts on the cutting edge who can help them with their particular problems.

By making it easier for academics to work in other EU countries, and organising cross-border funding, researchers believe the EU enabled European science to do better.

Impediments to accessing the European research network would be keenly felt.

Universities UK, the umbrella body for the sector, estimates that more than 60% of the UK's international research partners are from other EU countries - and collaboration with other EU institutions is growing at a faster rate than relationships with other partners, such as the US or China.

There are also serious concerns about funding shortfalls in particular areas, prioritised by the EU, which - if the UK leaves the European research infrastructure - a future UK government may choose not to back.

Jonathan Adams, chief scientist at Digital Science, which analyses research effectiveness, says: "Leading groups which are critical to economy and society such as nanotechnology and cancer research receive significant amounts of funding from Europe."

So, he said do "smaller universities regionally distributed that are important to the regeneration of industry".

Watch Chris Cook's report on BBC Newsnight at 22:30 BST on BBC Two - or catch up afterwards on iPlayer