Brexit: The Irish dimension

- Published

You may remember Roisin Hogan from the BBC's Apprentice programme. Two years ago, the accountant, from the Republic of Ireland, pitched a business plan based on a new health food.

"I was fired in front of 10 million people," she tells me with a giggle.

It may turn out to be one of the best things to have happened to her.

Ms Hogan and I are sitting in an office at Nature's Best.

It is a company you probably have not heard of, because the salads it produces are sold as supermarket own brand.

And Ms Hogan's noodles, called Hiro, will be produced here, a sideline for a business that had a turnover of 24m euros in 2014.

But both she and Paddy Callaghan, the founder of Nature's Best, have to adjust to a new - and, for them, unwelcome - development, the aftermath of the UK vote to leave the European Union.

Ms Hogan tells me major British retailers were interested in stocking her product.

And the interest is still there, but the collapse in the value of the pound makes it much more expensive to import.

So either her small start-up absorbs the currency depreciation - between 10 and 16% - or the British retailers are likely to pass.

Mr Callaghan, an ebullient character who began his business 30 years ago, cultivating bean sprouts in his garage in Drogheda, probably has greater capacity to absorb extra costs.

But, as he points out, margins in the salad business are narrow, and with exports to the UK accounting for one-fifth of his business, he is keen to see a quick recovery in the value of the pound.

Most of those UK sales are to Northern Ireland. And the border is the main topic of conversation among business people in the Republic right now.

Peter Murray, manager of Buttercrane shopping centre in Newry, County Down, says the number of visitors from south of the border, which is about five miles away, is up by almost 50% because goods in Northern Ireland are now cheaper than in the Republic.

Theresa May and Enda Kenny have said that border checks will not return

Declan McChesney, of Cahill Brothers, a shoe shop in Newry, is unimpressed by last week's promise from Prime Minister Theresa May and Enda Kenny, her Irish opposite number, that border checks will not be reinstated.

"That is what we call in Newry a politician's promise, and, let's be honest, that does not give us much room for hope," Mr Chesney says.

"I cannot see how they are going to have free passage and free movement of goods if they don't have a record of it. And if you don't have a record of it, there will have to be a way of finding it and there will have to be some sort of checks, we suspect, which means a hard border."

The situation could become even more complex if the UK also withdraws from the customs union that underpins the EU's trading relationships.

The International Trade Secretary Liam Fox told the Financial Times to do so would give him more flexibility in negotiating new trade deals with countries outside the EU.

But Brian Lucey, professor of finance at Trinity College Dublin, says it could mean extra paperwork as goods pass in and out of the customs union, in which the Republic of Ireland would remain, and provide fresh opportunities for smuggling goods across the border, which in the past has helped to finance paramilitary groups.

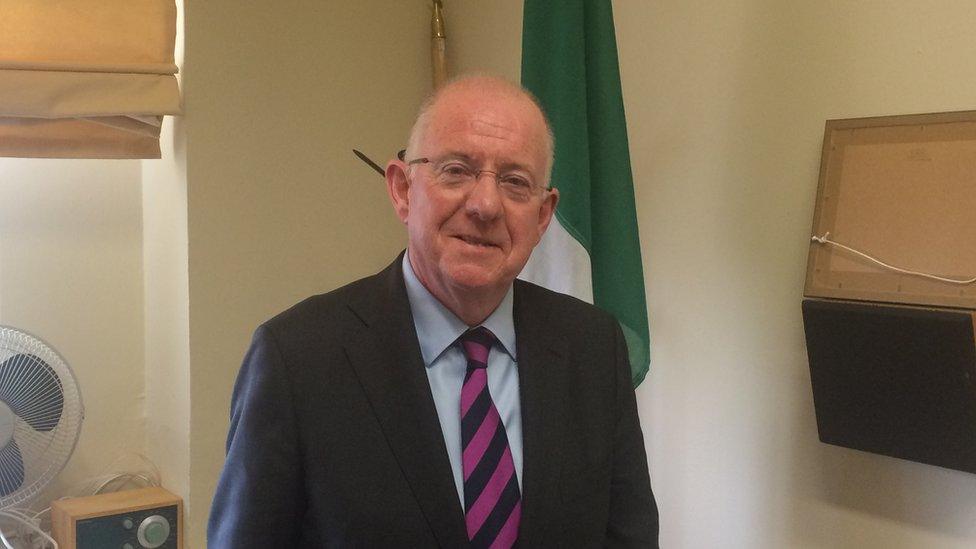

The Republic's Foreign and Trade Minister, Charlie Flanagan, believes an end to free movement is "simply unenforceable"

Border posts still exist but are unused.

In his office in the Dail, the Foreign and Trade Minister, Charlie Flanagan, tells me the only indication of a border most people will notice is the transition from signs showing km/h to mph, or vice versa.

I ask him whether it is possible to square the promise from the taoiseach and the British prime minister that there will be no return to a "hard border" and the determination to end free movement of European nationals in the UK.

"It is," he replies, "simply unenforceable."

Theresa Villiers, who spent nearly four years as Northern Ireland Secretary until Mrs May became prime minister, disagrees.

She thinks employers in Northern Ireland will be able to ensure they do not employ EU workers, without the need for immigration officers to police the border.

The complication here is the status of the people of Northern Ireland and the Republic.

Fifty years before the UK and the Republic of Ireland joined what was then the EEC - both of them on the same day, as it happens - the two countries adopted a free travel area.

Whether citizens of the UK or the Republic, they have been able to travel and work freely in either country.

After Brexit, that should continue - but even employer checks on other EU nationals could begin to erode the hard-won trust between north and south.

And that, more than currency fluctuation or economic uncertainty, is what is really making people nervous on the island of Ireland.

Shaun Ley presents The World This Weekend during the summer, at 1300 BST on Sundays, and afterwards available on the Radio 4 website.