What sort of Brexit does Philip Hammond want?

- Published

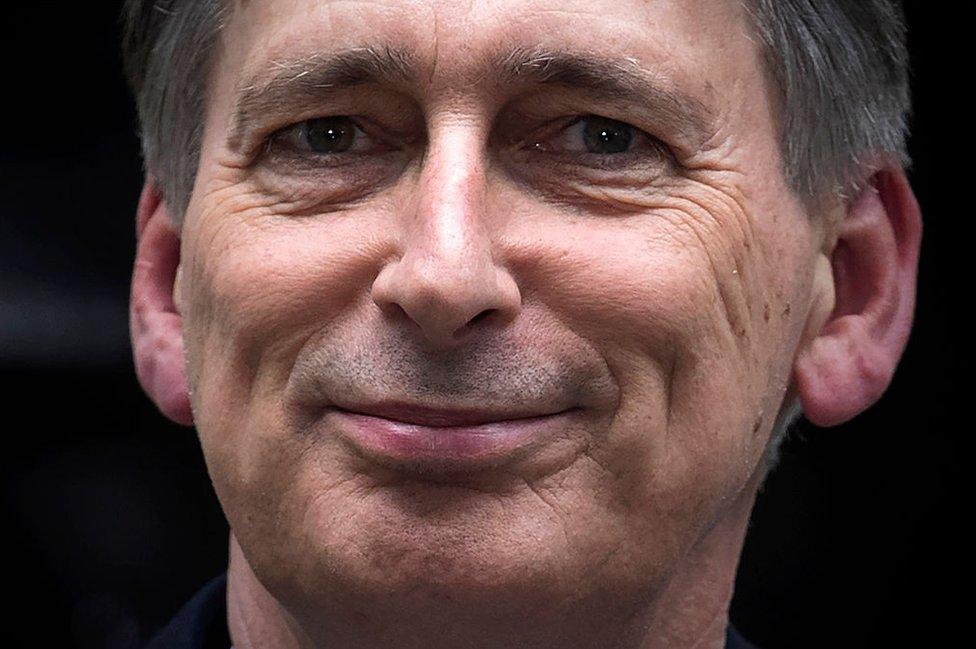

What does Chancellor Philip Hammond's increasingly vocal stance on Brexit say about his intentions, his prime minister and his party?

Is the chancellor intent on using his soft power to take on the hard Brexiteers? He's certainly using it to isolate one very vulnerable prime minister.

Mr Hammond, while seemingly content to let her remain in political limbo, has also vented his frustration about his boss, making it clear that Theresa May's team had made sure he had been shut away during the election, forbidden to talk about the economy.

He has suggested that this was the key, fatal, majority-losing mistake.

His message now: "It's the economy, stupid," and that goes for Brexit too.

Monday's talks in Brussels are one baby step on a long journey to a new future.

The election has changed everything. There are those in the Conservative Party who think the lesson was clear: hard Brexit has been rejected.

"Our power is now limited. To say it is a mess is to state the bleeding obvious," one former minister, an ardent campaigner for Leave, told us.

Mr Hammond has criticised Theresa May's general election campaign

A former minister on the other side of the debate made it clear she had kept her seat because she was an ardent Remainer and was pinning her hopes on the chancellor softening Brexit.

Whether or not the chancellor is "on manoeuvres", Mr Hammond is certainly marshalling his arguments.

A planned Mansion House speech was postponed because of the Grenfell fire, but was briefed as potentially lobbing a missile into Number 10 and that the chancellor was toying with the idea of arguing to stay in the Customs Union.

He hasn't done that. Instead, he told the BBC's Andrew Marr programme that he would prioritise the economy, jobs and skills, while adding: "We're leaving the EU and because we're leaving the EU we will be leaving the single market. And by the way, we'll be leaving the Customs Union." The postponed speech will now be delivered on Tuesday 20 June.

In a wider context, to understand the chancellor's language you have to decode the debate and the movement of the Tories biggest beasts, those who consider themselves the natural rulers, who feel that those they see as rebels, or Leavers, have seized control of their citadel.

It looks as if a counter-strike by these forces is unfolding before our eyes.

Consider: two former prime ministers, John Major and David Cameron, who were humiliated by Eurosceptics, have backed Mr Hammond's view, calling for the economy to be put first and for an agreement on Brexit with other parties.

So has former Conservative leader William Hague. So has the only Tory hero of the hour, Ruth Davidson, the Scottish Conservatives' leader.

Almost unnoticed, the generally rather underwhelming reshuffle was at the heart of the coup.

Chancellor Phillip Hammond secure in place, Remainer Damien Green elevated to First Secretary of State, Remainer Gavin Barwell, former Croydon MP, the prime minister's new chief of staff, a critical appointment.

David Cameron and Sir John Major have both backed Mr Hammond's stance on Brexit

Brexit Secretary David Davis's top team has been eviscerated. His main ministerial enthusiast for leaving the EU, David Jones, was sacked without warning. The other resigned. The department didn't know it was coming. More importantly, Mr Davis didn't know it was coming.

One ally and former minister told us: "It's a major blow. David is now isolated, he is concerned that half his senior team have been swept from beneath him."

Another friend ruefully admitted that Mr Davis's hand had been weakened by the loss of close allies but is hoping he is strong enough to stand firm without them.

But the signs are that the core, indefinable, establishment of the Conservative Party, the party of business and occasional populist nationalism, is seizing back control.

If the softies are on the rise, what is it they want?

"Putting the economy first" is code for lots of things from staying in the single market, to staying in the Customs Union, to staying in the European Economic Area.

Mr Hammond believes that the economy and jobs should be prioritised in Brexit talks

But two things are at the heart of their demands.

First, a gradual, gliding process of leaving the European Union, gracefully shedding its laws, institutions and benefits only very slowly: a "transitional arrangement" in the jargon. It is never said, but presumably this transition can be frozen into permanence at any point.

Then, there's the rejection of Mrs May's contention that "no deal" - a very hard Brexit - is better than a bad deal.

Some complain that "hard" and "soft" Brexit are meaningless, crude terms. They are correct to the extent that, like "left" and "right", they are big holdalls containing disputed goods.

But, in this case, the key to the argument is immigration. At the heart of soft Brexit is a compromise: getting better access to the single market by ditching tough demands on immigration.

So what did Mr Hammond say? He repeatedly emphasised that Brexit required a "slope not a cliff" and that no deal would be "a very, very bad deal" although one purpose-built to punish would be worse.

Immigration will be a key topic in the Brexit negotiations

He explicitly said he wanted as close to the tariff- and trade-barrier-free single market as we could get. That implies giving up something on immigration.

So far it isn't enough to rile the right on the backbenches, but it leans heavily on one side of the debate.

But peer into next year, and it is the sort of deal that might need the support of Labour, Lib Dem and SNP MPs.

There is already detailed thinking about such a temporary Macronist alliance - akin to that which has just swept through French politics - in the voting lobbies.

But maybe, just maybe, none of this is really about a final agreement with the EU but an interim one with cabinet colleagues.

Few think Mrs May can survive long. There will probably be a leadership contest within the next few years, very possibly within the next few months.

Few want to, to coin a phrase, jump off a cliff, and rather fancy instead sloping towards the future.

Though still keeping his own Brexit cards close to his chest, Boris Johnson wrote yesterday about an "open Brexit" and not "slamming the drawbridge on talent".

A very public message about the price for support in a leadership contest perhaps?

There's some hard politics behind the soft option.

- Published14 August 2017

- Published5 May 2017