Does it matter if the UK leaves Euratom?

- Published

On 29 March Theresa May sent a six-page letter notifying the EU of the UK's intention to leave. The Article 50 letter contained a clause little discussed at the time - notifying the EU of the UK's withdrawal from the European Atomic Energy Community, also known as Euratom.

But this previously obscure section has now been put under the political spotlight, with some MPs, including a number of Conservatives, gearing up for a fight on the subject. One prominent Leave campaigner has even said the UK should stay in Euratom after Brexit.

On Thursday, the government will clarify its stance on the issue in a position paper. But what is Euratom and why does it matter?

What does it do?

Euratom regulates the nuclear industry across Europe, safeguarding the transport of nuclear materials, disposing of waste, and carrying out research. It was set up in 1957 alongside the European Economic Community (EEC), which eventually morphed into the EU. The 1957 treaty established a "nuclear common market" to enable the free movement of nuclear workers and materials between member states.

A nuclear reactor under construction in northern France

The UK joined Euratom when it joined the EEC in 1973. It is a separate legal entity from the EU, but is tied up with its laws and institutions, and subject to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (ECJ). No country is a full member of Euratom without being a member of the EU.

When EU countries transport nuclear materials or trade them with other countries, Euratom sets the rules. The body also co-ordinates research projects across borders. For example the Culham Centre for Fusion Energy, a laboratory near Oxford, is largely funded by the EU and many of its scientists are EU nationals.

The Culham Centre for Fusion Energy

Euratom also reports to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). If the UK were to leave Euratom it would need to come to a new arrangement with the IAEA.

What are the reasons for leaving?

There are two main arguments why Brexit should involve quitting Euratom.

Firstly, staying in would raise lots of tricky legal questions. For example, the Euratom treaty states that it applies only on the territory of EU member states. Legal opinion is divided on whether a country could leave the EU and retain Euratom membership, according to research by the House of Commons library. But the UK government has made up its mind.

"The triggering of Article 50 on Euratom is not because we have a fundamental critique of the way that it works. It was because it was a concomitant decision that was required in triggering Article 50," said Brexit Secretary David Davis.

The second reason for quitting Euratom is the government's interpretation of the Brexit result. Vote Leave campaigned to restore British sovereignty and "take back control" by ending the supremacy of EU law over domestic law.

In her speech to the Conservative Party conference in October, Theresa May made this rather more specific, pledging to ensure "the authority of EU law in this country ended forever". This stance has been called the "ECJ red line" - in other words stopping the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg having any authority in the UK.

October 2016: Theresa May promises to end "the authority of EU law in this country"

The nuclear agreement is underpinned by the ECJ. That means if states signed up to the Euratom treaty breach its terms, they can be hauled before European judges. This could happen to Britain after Brexit, if it remains signed up to Euratom. Full membership would apparently be incompatible with a strict interpretation of the ECJ red line.

Also, the Euratom treaty requires members to allow the free movement of nuclear scientists, which could fall foul of the government's wish to cut net migration drastically from its current level.

What are the reasons for staying in Euratom?

Dominic Cummings, who was campaign director of Vote Leave, this week criticised what he called "government morons" who want to withdraw from Euratom. "Tory Party keeps making huge misjudgements re what the REF was about. EURATOM was different treaties, ECJ role no signif problem," he said on Twitter.

Although the agreement is overseen by the ECJ, the court does not intervene very often, according to those who want to stay in.

Conservative MP Ed Vaizey and Labour MP Rachel Reeves published an article in the Sunday Telegraph, external this week defending Euratom membership. "There appears never to have been an ECJ case involving the UK and Euratom," they said. "Whatever people were voting for last June, it certainly wasn't to junk 60 years of co-operation in this area with our friends and allies."

James Chapman, a former special adviser to David Davis, has also criticised the application of the "ECJ red line" to Euratom: "I would have thought the UK would like to continue welcoming nuclear scientists who are all probably being paid six figures and are paying lots of tax," he told the BBC last month. "But we're withdrawing from it because of this absolutist position on the European court. I think she [the prime minister] could show some flexibility in that area."

What will happen to cancer treatment?

Mr Vaizey and Ms Reeves also raised the issue of cancer medication. Euratom supports the "secure and safe supply and use of medical radioisotopes". Radioactive isotopes are essential for various types of cancer treatment but cannot be stockpiled because they decay quickly.

In the UK they are imported, often from Belgium and the Netherlands. Some experts worry that leaving the treaty will delay the delivery of drugs to patients who need them. Global demand for isotopes is rising rapidly, and many of the reactors that produce them are getting old.

Radioactive isotopes used to treat cancer

The government's answer to this is that medical isotopes are not fissile nuclear material - that is, capable of reacting - so they are not subject to international nuclear safeguards. According to Science Minister Jo Johnson, their availability "should not be impacted by the UK's exit from Euratom".

Is this a proxy war?

In February, Parliament passed a bill giving the government permission to trigger Article 50. Labour MPs tried to add an amendment keeping the UK in Euratom, but it was comfortably voted down.

Last month Theresa May's Conservatives lost their majority in the general election, which has emboldened opponents to the government's Brexit stance.

Though the government's position has been firmed up by signing a confidence-and-supply deal with the DUP, it can still lose key votes if just seven Conservatives vote the other way.

Several of Ed Vaizey's colleagues have backed his position on Euratom. Given the Labour manifesto pledge to "retain access" to the nuclear agency, this means the government could well lose a vote on the issue.

A chain reaction

Given that Euratom was explicitly mentioned in the Article 50 letter, any reversal of withdrawal would be difficult, and an act of Parliament would probably not be enough.

Changing or reversing the UK's withdrawal from Euratom would probably need to be done formally by the government. If that were to happen, it would raise another contentious legal question - whether the notification of withdrawal from the EU can be amended or revoked. The government really does not want to open that can of worms.

What's more, staying in the nuclear agreement would not be a matter purely for the UK to decide. The EU, which has published a position paper, external on Britain's departure from Euratom, would also have to agree. That could make things complicated.

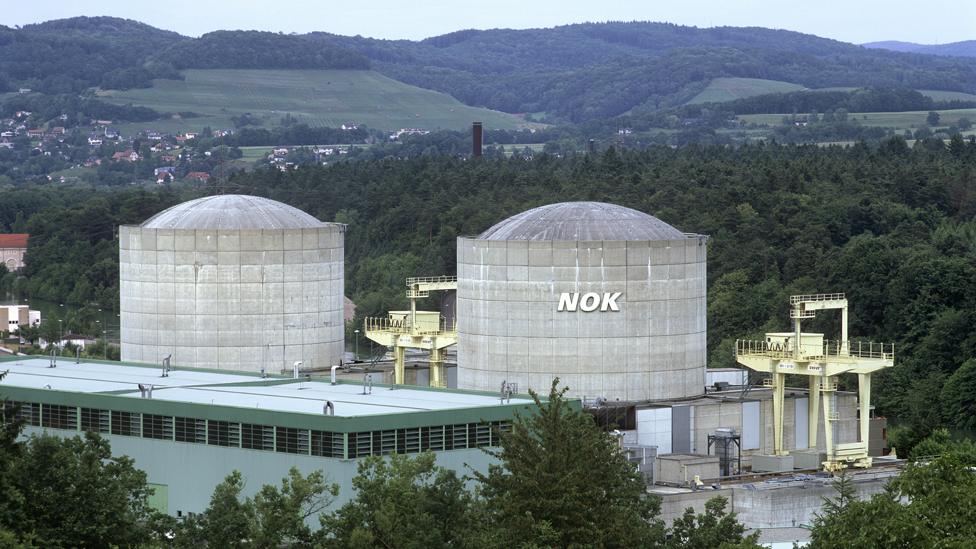

Various options have been mooted for an alternative to full Euratom membership. Switzerland, not an EU member, has a special status as an equal partner as an "associated country". This could be an option explored by the UK. But sticking to the ECJ red line might make that path difficult.

Beznau nuclear power plant in Switzerland - the country is a partner with Euratom

Euratom also has looser co-operation agreements with other countries such as the US and Australia. These third-party countries help fund projects such as the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor in France, which is run by Euratom. But moving to a looser agreement could cause disruption when the UK is so integrated into the EU's nuclear energy market. Given the long timescale needed for nuclear projects, scientists worry about the uncertainty.

A nuclear future?

The final arrangements between the UK and Euratom after Brexit will have big repercussions for a country which is committed to atomic energy for the long term - unlike Germany, which ditched nuclear power in the wake of the 2011 Fukushima disaster.

Last September the government approved a new £18bn power station, financed by the French and Chinese governments, at Hinkley Point in Somerset.

Hinkley Point in Somerset is to be the site of a new nuclear power station

Sellafield, where plutonium is reprocessed and stored, is Europe's largest nuclear facility. The Cumbria site has the largest stockpile of civil plutonium in the world. Euratom runs the on-site laboratory there, and also spends a big chunk of its EU-wide resources running safeguard checks there. There's also the centre at Culham, where Euratom plays a big role.

In May the Commons Energy Committee, which has been investigating the impact of Brexit on energy policy, urged the UK to delay leaving Europe's nuclear regulator. Power supplies could be threatened if a new regulator was not ready, it said.

Whatever decision is finally made on Euratom, it will matter for decades to come.