A profile of SNP leader Alex Salmond

- Published

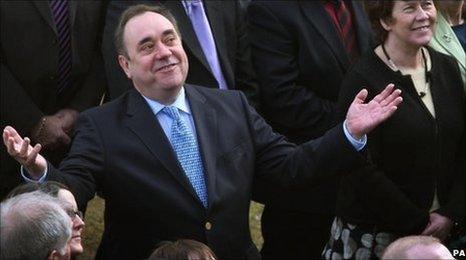

Alex Salmond is seen as one of the most prolific politicians of his generation

Love him or loathe him, few would dispute Alex Salmond's skill and achievements as a politician.

He is a man who has spent his whole political career dividing opinion.

Mr Salmond's political beginnings as a brash, yet passionate, outsider have never disappeared - even when he turned statesman as the head of Scotland's government and his beloved Scottish National Party.

As one of the most talented politicians of his generation, he has now brought the SNP as close to its dream of independence as it has ever been, in the wake of a landslide election win and a deal to hold a referendum in 2014.

The SNP leader has now reached another milestone, becoming Scotland's longest-serving first minister, breaking the record held by his predecessor, Labour's Jack McConnell.

Mr Salmond's reputation as a hot-headed and rebellious character ensured he was a high-profile politician long before becoming first minister of Scotland.

Born on Hogmanay 1954 in the ancient and royal burgh of Linlithgow, Alexander Elliot Anderson Salmond graduated from St Andrews University and began a career in economics, working for the Scottish Office and the Royal Bank of Scotland.

He also played an increasingly active role in the Scottish National Party, having come to the conclusion that the economic case for independence was strong.

His initial rise to prominence, both inside and outside the party, came as the SNP entered its darkest period.

The 1979 General Election, which resulted in victory at the polls for Margaret Thatcher's Tories, saw the number of Nationalist MPs slashed from 11 to two.

Mr Salmond played a prominent role in the breakaway '79 Group, which sought to sharpen the SNP's message and appeal to dissident Labour voters after the party's collapse - a move which earned him a brief expulsion in 1982.

Reflecting on the incident years later, he put it down in part to his being a "brash young man" - although the urge to cause a bit of mischief has never been far from his mind.

Despite his form, Mr Salmond established himself as a rising star of the SNP, winning the Westminster seat of Banff and Buchan in 1987 - and notably getting himself banned from the Commons chamber for a week after interrupting the chancellor's Budget speech in protest at the introduction of the poll tax in Scotland.

When the job of party leader came up in 1990, Mr Salmond made his move and, on winning the post, repositioned the SNP as more socially democratic and pro-European.

The delivery of Scottish devolution presented new opportunities for the SNP. The party failed to win the first Holyrood election in 1999, but won enough seats to set itself up as the official opposition.

During the campaign, Mr Salmond had sparked controversy when he described Nato action in Kosovo as "an act of dubious legality, but, above all, one of unpardonable folly".

After putting in a decade as SNP leader, Mr Salmond made the decision to quit and stand down as an MSP.

Leadership challenge

He returned to Westminster, where he had built up a high profile, partly from his many appearances on TV programmes ranging from Question Time to Have I got News for You.

Mr Salmond has also put his love of horse racing to good use, appearing as a pundit on Channel 4's The Morning Line programme, as well as offering tips and insights through the pages of the Racing Post.

John Swinney - later to become Scottish finance secretary - succeeded Mr Salmond as leader, but stood down in 2004 following continued criticism from sections of the party and the negative publicity of a leadership challenge.

Many turned to Mr Salmond to grasp the thistle and take his old job back.

He responded by borrowing from Union Army General William Sherman, who, on being asked to run for president following the American Civil War, declared: "If nominated I'll decline. If drafted I'll defer. And if elected I'll resign."

As it was looking like Roseanna Cunningham was a front-runner for the job, Mr Salmond entered the leadership race, "with a degree of surprise and humility, but with a renewed determination".

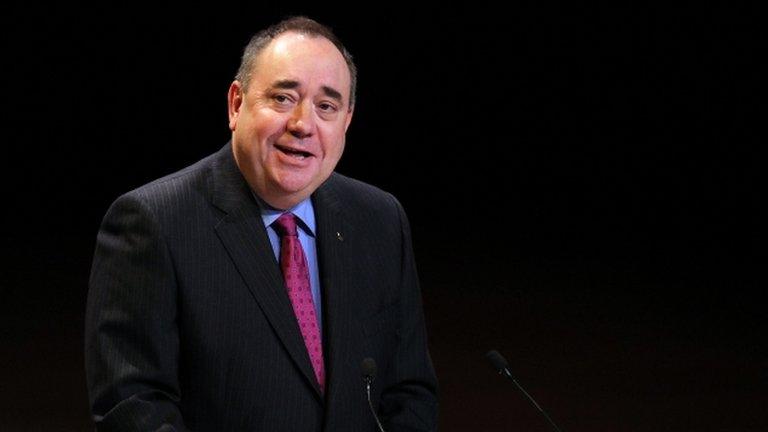

Alex Salmond is known to be a hot-headed and rebellious character

Essentially, as he put it himself: "I changed my mind."

Following the comeback, on a joint ticket with deputy Nicola Sturgeon, Mr Salmond led the SNP to its greatest hour yet - victory at the 2007 Scottish election and delivery of a minority SNP government.

He also reinvented himself as something of a new man - at least initially.

Gone was the "Eck" of old, known to respond to tough questions in an aggressive manner - replaced with a more measured and positive, even chirpy, character.

Behind the scenes, colleagues and staff were expected to keep up with his extraordinary drive - with the old flash of the Salmond temper still putting in a public appearance.

Mr Salmond also achieved a personal victory in the election, winning the Liberal Democrat-held Scottish Parliament seat of Gordon, providing the vehicle for his return to Holyrood.

Gordon Brown, still Chancellor at the time, called Mr Salmond to congratulate him becoming first minister - four weeks after the election.

It was not long before the first predicted brush with the UK Labour government. The subject was the future of the convicted Lockerbie bomber Abdelbaset al-Megrahi - who was later released by the Scottish government on compassionate grounds on account of his terminal illness in the face of huge criticism from the US and others.

In a BBC interview marking his first ministerial milestone, Mr Salmond said, looking back, that the fallout of the decision resulted in "difficult days".

And despite a row at the 2012 SNP conference over it's U-turn to Nato opposition and criticism over the government's handling of the existence of EU legal advice on an independent Scotland, Mr Salmond added: "In the league table of stooshieness, the last couple of weeks is pretty minor compared to Megrahi."

As the SNP's term in government progressed, there would be many more arguments with Westminster, on topics ranging from energy policy to Treasury funding and, more recently, the terms of the independence referendum.

As the global economic meltdown took hold, Mr Salmond blamed "spivs and speculators" for the problems which caused the takeover of HBOS, as the crisis of confidence in the financial sector hit Scotland.

'Cavalier approach'

He later faced criticism from political rivals who said HBOS's real problems were caused by the bank's exposure to the volatile mortgage market.

In contrast, though, the Glasgow Airport terror attack and foot and mouth crisis showed how willing the first minister was to work with Westminster on issues of UK importance.

In 2008, Mr Salmond was accused of taking a "cavalier" approach to dealing with US tycoon Donald Trump's £1bn Scottish golf resort.

An inquiry into the affair by Holyrood's local government committee raised concern over the Scottish government's decision to call in the plans, following their rejection by Aberdeenshire Council, after "two five-minute phone calls".

The probe concluded the decision, although unprecedented, was competent. It was the classic Salmond approach to problem-solving.

Two years later, Mr Salmond came under fire for his involvement in saving the troubled international clan gathering event in Edinburgh.

The SNP was criticised for bailing out the event organisers with an interest-free taxpayer loan not widely publicised at the time.

Alex Salmond was elected as an MP in 1987

In his usual style, Mr Salmond later conceded the government could have told other public bodies involved with the event about the loan, but remained defiant, insisting the action saved an event worth £10m to the economy.

Then came the 2010 UK election.

The SNP had already delivered a crushing blow to Labour, winning the Westminster seat of Glasgow East in a by-election (which Labour later re-claimed).

Mr Salmond's campaign strategy was to back a hung parliament at Westminster, combined with an ambitious plan to significantly boost the number of SNP MPs so they might hold a balance of power, when it came to making key decisions - to "make Westminster dance to a Scottish jig," as he put it.

But, in the event, with a resurgent Tory party on course for victory, Scots voters came out in their droves to back Labour.

It was also a campaign which saw the SNP unsuccessfully take the BBC to court, after it was decided Mr Salmond would not take part in the TV debate with Gordon Brown, Nick Clegg and David Cameron.

With the polls giving Labour as much as a 15-point lead, it seemed the party was on course for a return to power at Holyrood in 2011.

But, never to be underestimated, Mr Salmond - who has always relished being the underdog - launched into the contest with a positive campaign.

Enigmatic persona

When he came up against Labour's negative, attacking style, Scots voters decided there was no contest - and the SNP was returned with an overall majority.

For Mr Salmond it was a jaw-dropping result - perhaps a once-in-a-generation shift in Scottish politics, which had seen Labour as the dominant force for 50 years.

The part-PR/part-constituency system at Holyrood was essentially designed to keep any one party (ie, the SNP) from winning an overall majority.

The re-elected first minister now had a mandate for the independence referendum, to be held in autumn 2014, the terms of which have now been agreed with the UK government.

Mr Salmond's party continued in government, with its policy of resisting Westminster cuts, protecting NHS spending and Scotland's cherished universal benefits, and its claims of achievement, like cutting crime to a 30-year low.

Moira Salmond is often seen supporting her husband, but the two closely protect their private lives

Opposition parties sought to portray Mr Salmond as being obsessed with winning the referendum to the point of neglecting Scotland's real social problems, while accusing him of watering down his vision of independence - on issues like keeping the pound and the monarch as head of state - to maximise the 'Yes' vote.

Away from the Holyrood chamber, the first minister has faced opposition accusations of close links with big businessmen - Stagecoach boss Brian Soutar, US tycoon Donald Trump - who later turned on Mr Salmond over his government's pro-wind farm policy - and Rupert Murdoch.

During the height of the News International phone-hacking scandal, rival parties asked why Mr Salmond was meeting the media mogul, while also demanding to know whether he himself had been a hacking victim.

The first minister insisted his relations with Murdoch were about promoting jobs for Scotland and, after weeks of questioning, he finally told the Leveson Inquiry into press standards his phone was not hacked - but that his bank account was accessed by the Observer newspaper in 1999.

Despite his style as a politician, Mr Salmond retains an enigmatic persona. He and wife Moira, who never had children, closely protect their private lives.

He is also known for his love of singing, having recorded a version of the Rowan Tree with artist Anne Lorne Gillies as part of a CD released to inspire independence.

And with opposition parties constantly quoting polls which put support for independence at about a third, could it be a case of so near, yet so far for his ultimate dream?

One thing is for sure - in a world where political leaders so often rise from within the establishment, Mr Salmond has made it with a totally unconventional approach, the like of which may not be seen again.

He would never have had it any other way.

- Published7 November 2012

- Published16 May 2016