The golden age that never was

- Published

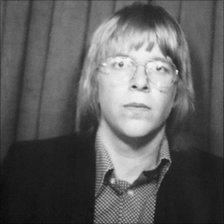

Kenneth Macdonald pictured 35 years ago, when he was starting university

Yes, that's me.

Velvet jacket, a shirt collar, whose dimensions even Harry Hill might consider a bit over the top, aviator specs. Well it was 1975, and this was my matriculation photograph.

I was a proud participant in the golden age of free university education. Or so I thought.

Apart from the essays and exams, it wasn't half bad. Students got grants, travel expenses, help with the rent - even the dole during the holidays.

Beer was 25p a pint. At least, I think it was - my memories of that period are somewhat hazy.

But was the age really golden?

As Professor Lindsay Paterson of Edinburgh University pointed out in Monday's programme, education has never been free. Somebody has to pay for it.

Back then it was the taxpayer.

"At the moment if you add together income tax faced by new graduates and the loan repayment element of the student loan," Professor Paterson said, "you get a marginal rate of, in effect, income tax which is lower than what was paid by graduates like us in the late 1970s."

The road to mass university education in Scotland has been long and slow. At the end of World War II, university was for an elite. Only about 4% of school leavers managed to get there by the time they turned 21.

By 2009 that figure was 43%.

These days there's ample evidence that a university degree boosts your earning potential.

But it also brings benefits for society as a whole. The more graduates a country has, the better its democratic institutions function. Health is better, prison populations are lower.

This balance of benefits has fuelled the debate over who should pay to fill the funding gap created by English universities being allowed to charge higher tuition fees.

One frequently floated possibility has been a graduate tax. But in some ways it looks like we already have one.

According to the universities' own figures, the 21% of Scots who are graduates already pay an estimated 44% of Scotland's income tax.

Meanwhile most mainstream politicians have booted into touch - for now - the idea of charging Scottish students tuition fees. While the universities fear the funding gap may be more than £200m, the politicians have seized on a more manageable estimate of £93m.

That shifts the debate back to two big questions: what is university for and what shape should university education take in the future?

The future will to come in as many shapes and sizes as there are undergraduate hairstyles.

Our universities already do. Some are local, some focus on building careers and businesses, others jealously guard lofty positions as big hitters in research or philosophy.

Kenneth Macdonald in another embarrassing photograph

The boundaries are blurring in other ways too. Tens of thousands of our higher education students aren't at university at all - they're studying university-standard courses at local colleges.

And then there's the increasingly prevalent idea that some students could, in effect, do their first year at uni while they're still at school - saving time and money.

But the four-year Scottish honours degree is likely to remain the norm - if only because there isn't enough time for more radical reform.

There's an election coming up and - for the politicians as much as our universities - the clock is ticking.

It's almost 35 years since I graduated (LLB, distinction in criminal law, conspicuous lack of distinction in every other subject) but it seems I have never lost my talent for appearing in embarrassing photographs.

Why a camel? You'll have to watch the programme to find out.