Can Glasgow become a dear greener place?

- Published

- comments

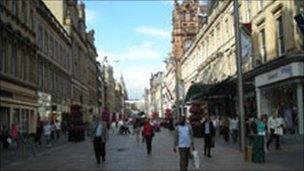

Plans for the digital quarter have been slowed up by the downturn

It's easy to see Glasgow as a problem, or to find problems when you consider its social and health challenges.

But the Glasgow Economic Commission has found no shortage of hopeful signs and opportunities.

Given the story that's told of dependency culture, who would have thought that it would perform well above similar cities in creating jobs in the eight years leading up to the recession?

It put on nearly 50,000 jobs, and saw 14% growth in private sector roles. Leeds and Manchester couldn't reach half that rate.

While a fifth of Glaswegians have no qualifications, leaving a long tail of blighted opportunity in much of the city, a third of its population are educated to degree level - the biggest pool of graduate labour force in Scotland, and a big attraction to inward investors.

Smart energy

That helps explain why the city is punching above its weight in adding new investors. Tesco Bank and e-sure are among those to see its financial service skills as a big pull.

But the Commission puts low carbon technologies at the top of its list of priority sectors. That includes renewable energy, as well as smart ideas to reduce energy use.

Glasgow saw a 14% growth in private sector jobs in the eight years before the recession

On that score, there's a significant cluster of expertise being built up, with high-value jobs attached.

Mitsubishi, Gamesa, Iberdrola and Scottish and Southern have all chosen Glasgow as their centre of engineering and operational expertise in handling ambitious moves into renewable energy.

Korea's Doosan has picked Renfrew for the same, where it already had a base, and is yet to say where its manufacturing base will be.

The commission's chairman, Professor Jim McDonald, as Strathclyde University principal, is enthusiastically harnessing the research implications of that.

Top priorities

Much of the report focuses on trying to get Glaswegians to work more effectively together, which risks stating the obvious.

But then, the city council, in recent memory, has not been all that keen to share its vision with others, including the business community. There seems more appetite for collaboration now.

The report is also clear that the retreat of public sector capital investment presents a challenge to innovate with other funding ideas, if developments in the east end, the Clyde waterfront and the city centre are to be continued.

Again, there's something a bit obvious about that, but it may need to be said if effort is to be put into solving the challenge.

A model for Glasgow operating at its best is the team that markets it for big events, conferences and conventions.

With the results of their efforts clear from the latest financial results from the Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre - a doubling of profits last year - that bureau is being put forward as the template for others to become similarly proactive.

Tourism and events is one of those five priority sectors, along with low carbon technology, engineering, life sciences and financial services.

Sparky creatives

The risk of that approach - which is also evident in Scottish Enterprise's cluster approach to targeting growth potential - is that it can exclude and constrain those not on the list.

The creative industries, for instance, are acknowledged as important employers in Scotland, but then rejected for the priority list.

That's after Glasgow planners putting significant effort into the digital quarter in Govan where the BBC and STV are based.

That plan has been been slowed up by the downturn. As one who works in it, it's clear to me the vision of a thriving, sparky hub of creativity is yet to be realised.

Glasgow has big potential in that sector, but it's pointed out in this report it's characterised by some large players, and then a long tail of very small firms and sole traders, with not much success at commercialising itself.

Pushing it down the priority list might be a mistake - particularly as the creative sector of the economy is essential to making the city a good place to live for all those engineers, biologists and financiers.

- Published3 July 2011