Govan Stones: The Viking-Age treasures

- Published

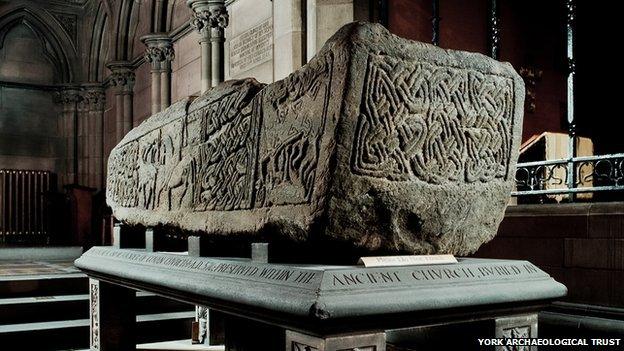

The sarcophagus dates back to about AD 900

A unique collection of Viking-age monuments, which lay unloved in a Govan churchyard for 1,000 years, has attracted the attention of the British Museum. Its curator said the Govan Stones was one of the best collections of early medieval sculpture anywhere in the British isles.

Govan is well-known as an industrial powerhouse which, over the past 150 years, has built an incredible number of the world's largest ships.

However the town, now part of the city of Glasgow, has a long and largely-forgotten history as one of the earliest seats of Christianity in Scotland and the main church of the Kingdom of Strathclyde, the lost kingdom of the northern Britons.

In AD 870, Vikings, who had been based in Dublin, destroyed Dumbarton at the mouth of the Clyde, which had been a major power centre in the centuries after the Romans departed from Britain.

As a result Govan, further up the river, took on a crucial role in the new kingdom of warrior chieftains that emerged to resist the Vikings.

Five huge hogback monuments are in the Govan collection

It is thought that the church at Govan may have been the main one for the kingdom of Strathclyde.

The Govan Stones are a collection of 31 recumbent grave stones, hogback stones and one remarkable sarcophagus from this period of history when warfare instigated by the Norse transformed the political landscape of Britain.

There had been 45 stones but a number were lost in the 1980s when the site of the neighbouring Harland and Wolff shipyard was demolished.

It is thought the stones from the 10th and 11th centuries, which had been lined up against a wall, were removed along with debris from the shipyard.

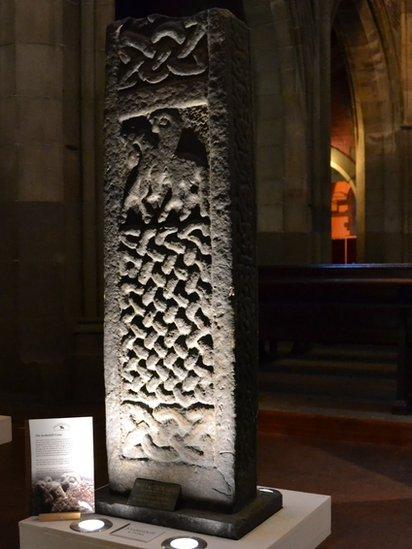

The most imposing monuments in the Govan collection are the five massive sandstone blocks, commonly known as the "hogbacks".

The solid stone blocks are not, as the name might suggest, representations of pigs but stones which are designed to make the tombs of the dead look like mighty buildings in the Norse style.

The recumbent stones, which often show hunting scenes and interlace patterns, were designed to be placed over a burial coffin

The hogbacks are found exclusively in areas of northern Britain settled by Vikings - southern Scotland, Cumbria and Yorkshire - and the Govan examples are by far the largest.

The bow-sided shape of the hogbacks is similar to the classic Viking house and the interlace patterns on them are also very Scandinavian in origin, according to Prof Stephen Driscoll, professor of historical archaeology at Glasgow University.

"It underpins this idea that this British kingdom of Strathclyde has some strong connections with the Scandinavian world," he says.

"My feeling is that this is meant to represent a lord's hall or a chieftain's hall.

"This type of monument, these hogback monuments, you only find them in Britain. You don't get them in Scandinavia and you don't get them before the Vikings come here.

"So somehow the Vikings come here and see they are in this world where people carve stones all the time and they think 'let's carve us a suitable stone that resonates with us'."

Although the beasts carved into some of the hogbacks could reflect pagan Viking beliefs, the fact that all these stones were found in a church yard suggests the settlers had taken to Christianity.

Even more impressive than the hogbacks is the monolithic sarcophagus which was found buried in the Govan church yard in the 19th century, without a body inside.

Prof Driscoll thinks this probably held the relics of St Constantine - the son of Pictish king Kenneth MacAlpin - who died in AD 876, ironically, fighting against the Vikings.

The sarcophagus of this Christian martyr, which is carved with hunting scenes and the same interlace that is seen on the other stones, was intended to take pride-of-place inside the church, Prof Driscoll says.

But it was probably stuck in the burial ground as an act of "iconoclasm" after the Reformation, he says.

"I think this sarcophagus is to house Constantine's relics as part of making this church into an important place," Prof Driscoll says.

"This is unique. There is nothing else like this in Scotland.

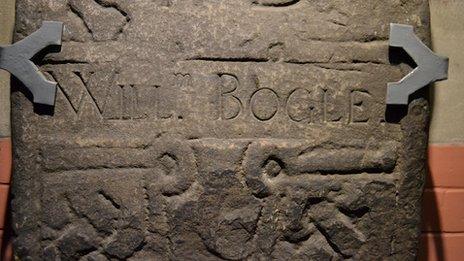

William Bogle had his name added to this ancient tombstone in the 18th century

"It was just not something they did at the time. If you were being buried you would put them in the ground.

"Sometimes they lined the graves with slabs but mostly they would be put in the ground in a wooden box or just a shroud, no matter who they were.

"If you are king they may put something special on top but this treatment is unknown.

"I'm sure they would have seen Roman sarcophagi when they went on pilgrimage and things like that. So they would have had the sense that emperors belong in a sarcophagus."

The other tombstones in the collection, though not as imposing to look at as the hogbacks or the sarcophagus, are also remarkable in the fact that they are only really found in Govan and Dumbarton, places which had a Royal association during the kingdom of Strathclyde.

Govan ceased to be important at the start of the 12th century when Glasgow emerged as one of the centres of the newly-ascendant kingdom of Scotland.

This massive changing of the old order meant that the old kingdom has been largely lost to history and only fragmentary records remain.

Prof Driscoll says the collection should be better-known

The tombstones at Govan were reused in the 17th and 18th centuries by local worthies, such as the Rowand family and William Bogle, whose name is inscribed into one of the ancient stones.

One of the stones was found in Jordanhill, on the other side of the river, where it had stood in the garden of one of the parishioners who had been given it as a gift.

Though there has probably been a church on the site since the 6th century, the current Govan Old church was only built in 1888 and is no longer in use as a parish church.

Prof Driscoll wants to raise the profile of the church and ensure its stones are given their rightful prominence.

A request from the British Museum to feature one of the hogbacks in a flagship exhibition Vikings Life and Legend, external, which begins in March, is an indication of the growing awareness of the importance of the sculptures.

Gareth Williams, curator of the British Museum Viking exhibition, said: "We wanted to go with one of the Govan ones because it is a particularly splendid example but also because we felt that it would be nice to put Govan on the map a bit more.

"It is a very important site and one which I think deserves to be better known.

"It is one of the best collections of early medieval sculpture anywhere in the British isles."

The smallest hogback, which weighs about 500kg, will be removed from the church and taken to London on Monday, the first time it has left Govan in a millennium.

- Published26 September 2013