Public art: What is it for?

- Published

A small-scale replica of The Kelpies has been on display outside the BBC in Glasgow

Every urban regeneration project seems to come with its own piece of public art. Scotland has a long tradition of art in public spaces. But what is it actually for?

When they are put into place next year, The Kelpies will stand a gargantuan 30 metres high (100ft) as a centrepiece of the regeneration of a 300-hectare site between Falkirk and Grangemouth.

Andy Scott working in his studio

At the workshop of Andy Scott, on a small industrial estate in Glasgow, sparks fly as a hooded figure welds one of the many metal pieces of sculpture, which are at various stages of completion.

Some show their eventual shape will be imposing; others are much smaller in scale. A thin layer of metal dust covers every surface.

Scott - the creator of The Kelpies - wipes his hands before shaking mine.

The equine sculptures, based on the Scottish legend of water-based spirits, are a reference to the role of the horse in Scottish agriculture and industry, Scott says.

He says: "There are lots of strands of narrative that I've pulled through."

Scott has already completed many other works of public art, perhaps most famously the heavy Clydesdale horse alongside the M8 motorway.

So what purpose does he think art, in this kind of setting, really fulfils?

"It's Scotland so you're never going to win everyone over," he laughs.

The Heavy Horse by the side of the M8 motorway

"But I'm pleased to say over the years, many of my pieces seem to have gathered quite a good public response."

The pieces themselves are inspired by the history and geography of the area for which they are destined, he says.

Scott describes the effect on some places as "humbling" - especially areas where there was "no expectation or anticipation of public art", he says.

"I've had some fantastic feedback from people - how they do create a sense of place or enhance their environments and give them a bit of pride in their area."

The history of public art in Scotland sees the Fife new town of Glenrothes playing a groundbreaking and hugely influential part.

In the late 1960s a town artist was appointed with a remit to contribute to the external, built environment.

Some of the art was landmark sculpture, using various materials including concrete, some of the town's underpasses became pieces of art themselves or the art was part of the buildings.

David Harding's work included public art in the underpasses of Glenrothes

David Harding, the town's first artist, dedicated himself to creating art, not for visitors, but embedded in the neighbourhoods of those who lived there.

He says: "You had a kind of monotony and repetition of building forms.

"What I felt I was doing was inserting unique little visual statements within these areas which contributed to giving them a kind of character of their own.

"Not only that, they also acted as kind of geographic guiding point.

"People would say 'you go along to the sculpture there and then you turn left'."

Harding felt it was important to involve local people and get them to contribute.

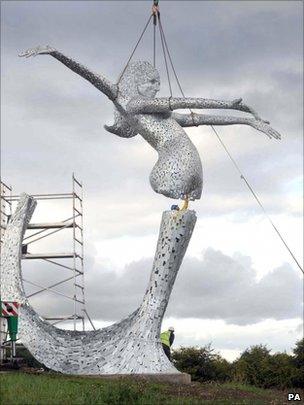

Andy Scott's Arria being put in place in August 2010

One of the first ways that was done was by getting local school children to make a very personal ceramic tile which they all cemented into a wall next to their playground.

Harding says: "It was especially important in new towns which were full of people from other places.

"New towns were difficult places for people to build up relationships and feel a part of and I felt that by doing this with the children they would feel a part of their town."

For many people nowadays the easiest way to spot public art would be on their daily commute, maybe at a roadside or a roundabout.

In the 1980s, for instance, there was a great trend for roundabout art.

Neil Baxter, of the Royal Incorporation of Architects in Scotland, says the best of public art can be "ironic" and "playful," all about taking art out of the formal setting of a gallery.

He says: "I suppose it's about enlivening places, it's about creating interest, it's about entertaining people. It can often have a humorous element - it improves your day."

He points to something like the Whirlies roundabout in East Kilbride.

"Those incredible stainless steel balls, like them or loathe them, they're a great landmark," Baxter says.

But what do the consumers of public art make of it all? Just outside Buchanan Street bus station in Glasgow is a clock standing on tall legs.

"I quite like the idea of time running by," one woman tells me, "because that's really what I always think of whenever I see it, because usually I'm rushing."

A clock on legs for people running late at Buchanan Street bus station

"I don't really know what it's supposed to mean," adds a man rushing out of the bus station.

Another woman says she does not like it, while a different one calls it "lovely".

Proof that artistic endeavour of any kind can provoke vastly different responses.

But with so much public art out there is it possible there could be too much?

Later in his career Harding became the head of the Environmental Art Department at Glasgow School of Art, which inspired a generation of conceptual artists such as Turner Prize winner Douglas Gordon.

He argues there is now masses of public art but critics in the media still focus most of their attention on galleries.

"Nobody writes critically of the work and I think that's where there's this big lack of quality," Harding says.

But even defining what public art actually is can be quite difficult.

"We know it makes a difference to have quality human environments," says Chris Fremantle.

He is one of the co-producers of Public Art Scotland, which is Creative Scotland's public art development programme.

"Art is a tool in the box, creativity is a tool in the box to help us address the challenges we face."

- Published29 May 2012

- Published11 April 2012

- Published18 July 2012