In yer ain wirds - What might we lose if we all began to speak like each other?

- Published

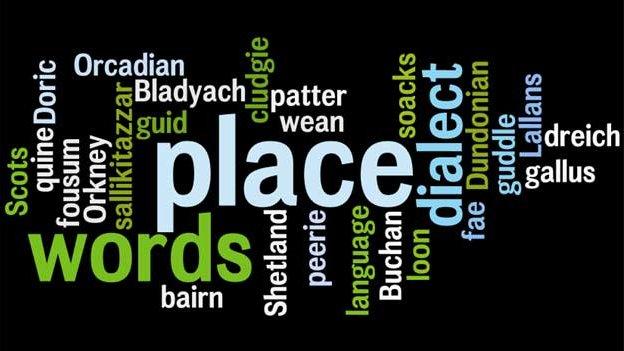

"Gallus" may be what some people in Glasgow are, a "bonxie," is a Shetland seabird and an Aberdeen girl could be a "quine". The length and breadth of Scotland is rich in dialects. What might we lose if we all began to speak like each other?

"There are all the unspoken things that go along with a word which tells you something about the culture," says Mary Blance who is part of the campaigning group Shetland ForWirds.

Its aim is to promote and celebrate the Shetland dialect, which has both Nordic and Scottish roots.

"Maybe a word like sprikkle," she continues.

"Sprikkle means to wriggle, to flounder, as when a fish is taken out of water.

Last native speaker

"I can remember telling a Shetland story on a stage somewhere, it was not in Shetland, and I was translating it in my head from the dialect into English and I was describing somebody holding a fish and it was sprikkling in their hand.

"I just could not, in that instant on stage, find a word that would explain sprikkle. So words are more than just what they mean."

That point was brought home with the recent death of the last native speaker of the Cromarty fisherfolk dialect.

Listen to archive of Bobby Hogg and his brother Gordon

It was of course an individual passing, but it also marked the loss of a living link to a part of a language.

It was deeply rooted in a place, reflecting the traditions and concerns of a community, containing words like "tumblers" for dolphins and harbour porpoises.

"Cromarty was very particular because that area was a Scots-speaking enclave surrounded by Gaelic so it was rooted very much in fishing communities there," explains Billy Kay, author of "Scots: The Mither Tongue."

He says very often the specific vocabulary of a dialect is associated with a very particular place and how people there made their living, like mining or working with horses.

The gallus style of Rab C Nesbitt's Glesca is very different from other dialects

"I'm from the Irvine valley in Ayrshire and the Irvine valley had speakers of the forerunner of Scots for maybe even more than a thousand years, there were people speaking the forerunner of these dialects and this language called Scots."

The Scots language centre (or the Centre for the Scots Leid) describes Scots as the national name for Scottish dialects sometimes also known as 'Doric', 'Lallans' and 'Scotch', or by more local names such as 'Buchan', 'Dundonian', 'Glesca' or 'Shetland'.

It says taken altogether, Scottish dialects are known collectively as the Scots language.

The 2011 census included a question about ability to speak the Scots language and information about that should be available later in the year.

However, the Scottish government says we do know that Scots is spoken widely, in different forms and in different communities throughout Scotland.

It says it has put a number of initiatives in place to encourage the use of Scots and Gaelic and to increase the profile of both languages.

In the area around Stranraer, some people call what they speak, Galloway Irish, characterised by broad vowels, a reflection of their proximity to Northern Ireland.

Local resident Elaine Barton says it can show the personality of what is a small place.

"People like to know who you are and one of my favourite sayings from a female perspective is 'Wha are ye tae yer ain name?'"

The Shetland word Bonxie is widely used for a Great Skua

This designed to winkle out a pre-marriage history.

That sense of place in language is to be found all over Scotland.

But the forces of global culture, such as film and television are often cited as a threat to more local languages and dialects. So what would we lose if we all begin to speak more and more alike?

"If we lose, Scots, even Scottish English, then we have lost something that will never be recovered," says writer, Mathew Fitt. He works in schools and elsewhere to promote the language.

"It's a way of seeing ourselves, being ourselves, communicating with each other in a way that no other people on the planet do."

He recalls his own schooldays and being belted for speaking Scots.

He argues that "there's still a lack of value being given to this language".

But if there are many global pressures on languages, including Scots and its dialects, there may also be some more positive signs.

The Shetland word Bonxie for instance has been more widely taken up by the bird watching community for the seabird, the Great Skua.

"In some places in Scotland dialects survive stronger than ever, in other places they're eroded," concludes Billy Kay.

"Linguistic change happens, very, very slowly and despite all the pressures against it, although we talk about languages dying I think what's more remarkable is languages surviving and in places like Aberdeenshire and Dundee or Ayrshire this language that's been there for a thousand years, thrives and does brilliantly."

- Published2 October 2012