Making tracks and political points

- Published

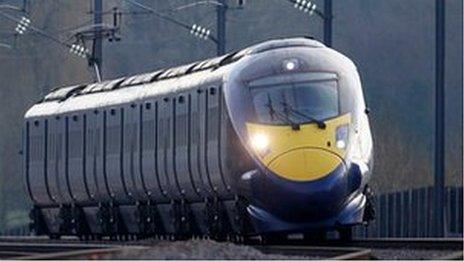

Scottish ministers are taking forward plans for a high-speed rail link between Glasgow and Edinburgh

If you want to travel between Glasgow and Edinburgh by rail, there are already four lines, going through Falkirk, Shotts, Airdrie and Motherwell.

That's not a bad choice. The most recent one, through Bathgate and Airdrie, was opened, or re-opened, two years ago, at a cost of £300m.

So is there a need for a fifth? Nicola Sturgeon seems to think so. Perhaps it's because she's a Glasgow MSP with a job in the capital.

The infrastructure secretary and deputy first minister started the week by suggesting a high-speed rail link between the two cities could be in place within 12 years.

This is one of the stranger ideas to come out of the Scottish government. It has no route, stations or price tag attached. It's not clear if the idea is for an upgrade or a new line, which would somehow have to find a route through built-up areas in the two cities. More trams anyone? And it doesn't even seem to have pressing demand for it, as the rail lobby has other priorities.

Electrifying

The idea comes only four months after the £1bn plan to upgrade the Edinburgh-Glasgow links, and much else in the central belt, was scaled down by £350m.

Faster journey times and electrification between the two cities remains part of the current programme, but this next stage of planning seems to have looped past parts of the EGIP that lost out when the budget was slashed.

So if a fifth line is to be built, or one of the current four substantially upgraded, it's not clear what happens to the shelved plans for electrifying lines through Stirling, Dunblane and Alloa, or the upgrade that could have linked Glasgow to the Forth Bridge.

That's why the politics of this is particularly odd. If there's to be high-speed rail linking Glasgow and Edinburgh, it doesn't look so good for the budgets necessary to upgrade rail links between the central belt and both Aberdeen and Inverness.

You also have to wonder how the Scottish government finds the transport budget to dual the A9 road between Perth and the Highland capital, which is already a commitment without a budget.

Those towns and cities outside the central belt may not be terribly happy to learn that Glasgow and Edinburgh are getting the big spending, again.

Building northwards

The rhetoric from Nicola Sturgeon suggests this is at least symbolic of a willingness to get on with high-speed rail, without having to wait for Whitehall, and England's commitment to it.

It's a response to the long wait for HS2, the high-speed route that's on schedule for a controversial route between London and Birmingham by 2026. Then, the budget would be sought to keep driving it north to Manchester and Leeds around seven years later, and then further north towards the Border.

Of course, building the link from Manchester to Carlisle can only be justified by the traffic between Scotland and the south. And one way of looking at such links is the Network Rail view that it only makes financial sense when you've built 400 miles of it, because that's when savings from journey times compete with air links.

So how would an independent Scotland and a newly-independent Rest-of-the-UK split the costs of the northern half of a very expensive new line?

Such links between member states have, in the past, enjoyed generous funding from European Union funds.

Would they be available in the current environment of pressured budgets in Brussels, pressure for spending in poorer parts of the union, and when it's not even clear if the UK is committed to staying in the EU? That would be a hard sell.

You can also comment or follow Douglas Fraser on Twitter: @BBCDouglsFraser

- Published12 November 2012