Scottish independence: Does the wording of the question matter?

- Published

What could be the big question on the Scottish independence referendum ballot paper?

To be or not to be? According to Shakespeare, that is the question.

The choice for Scotland in the autumn of 2014 is to be or not to be an independent country.

Simple question? Some observers of the referendum debate would say it is not.

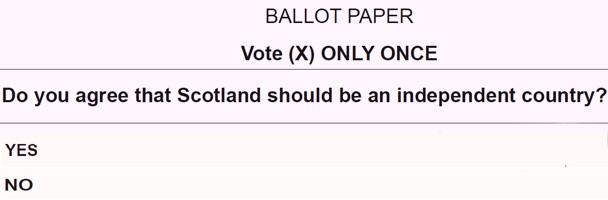

Both sides agreed last year that the Electoral Commission should scrutinise the SNP government's preferred "yes/no" question: "Do you agree that Scotland should be an independent country?"

The elections watchdog tweaked those words and reported that the question should be: "Should Scotland be an independent country?"

The commission said the question must be presented clearly, simply and neutrally.

The Scottish government agreed to changing the question when the commission reported its findings.

Referendum expert Matt Qvortrup said he did not think the original question was a problem.

The psephologist from Cranfield University says: "Well it certainly is not a biased question if you compare it to referendums which have been asked around the world.

"It is relatively common that the word 'agree' or a similar word is used."

However, Martin Boon, who is a director at polling firm ICM Research, says he would not allow a question structured in the original way to be used in one of his surveys.

He says asking, "do you agree?" puts the question into an "overwhelmingly positive light".

Mr Boon explains: "The question is not alerting people to the fact that they can easily disagree, which would be standard practice within the market research world.

"If that were the accepted question it should be revised to my mind to 'do you agree or disagree Scotland should become an independent country?'"

The SNP's original question was "unidimensional", said Prof Paddy O'Donnell.

The social psychologist added: "There is an expectation in the question that you are going to agree with it."

The University of Glasgow professor says people do not like disagreeing and they are far more likely to be agreeable.

"Most people want to agree with whatever someone is saying to them. That is the point.

"They have a response that is to agree with questions. There's more 'agrees' than people who say 'no' to everything that is being proposed."

Prof O'Donnell also points to what he thinks is a second problem with question - its lack of context.

'Too lacking'

He says it asks people to agree with the principle of independence, but does not give them any of the detail, on issues like whether Scotland would get all the oil money, would it be part of the European Union and a whole host of other questions.

Prof O'Donnell adds: "You could say, 'in light of what is being proposed do you agree?' and refer them to something else, another document where you can find all the context.

"Otherwise the question is too lacking."

The 1979 referendum on Scottish devolution failed despite the majority of those who voted being in favour, because the result did not meet a pre-determined voting threshold.

"It asked: Do you want the provisions of the Scotland Act 1978 to be put into effect?"

This assumed the voter cared enough to have read the document before voting.

A similar, though perhaps even more extreme example, is the question on accepting the Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland in 1998.

Voters were asked: "Do you support the Agreement reached at the multi-party talks on Northern Ireland and set out in Command Paper 3883?"

Prof Qvortrup says: "The interesting thing about the command paper question in Northern Ireland is that it was taken for granted that people knew what it was all about.

"There was that long campaign and Bono was on stage with David Trimble and John Hume.

"There was all that shenanigans leading up to that referendum on the Good Friday agreement in 1998, and all that energy and all that focus from the media meant you could have just had the words 'yes' or 'no' on the ballot, because people knew perfectly well what it was all about.

"They were probably able to cite chapter and verse from the agreement."

For Prof Qvortrup, this is the most important point.

He says the question is not vitally important because people will know before they enter the polling place what their views are on independence.

Prof Qvortrup says: "The overall conclusion one can draw if one looks around the world, is that question itself extremely rarely has an impact on the outcome of the referendum."

The ballot as proposed by the Scottish government earlier this year

The UK has historically held very few referendums and the ones which are held tend to have long campaigns giving people plenty of opportunity to make up their minds.

However, in countries such as Switzerland, as well as in many American states, they often hold several referendums on the same day and people may be voting without seeing the question in advance.

"But if you look at countries where there is one referendum, say, every few years, there's been a long run on to the referendum where the issue has been debated at considerable length, then people would have made up their minds before going into the polling booth and words of the questions is then of relatively minor importance," says Prof Qvortrup

In the Canadian province of Quebec, they have held two referendums on independence.

Prof Qvortup says in 1980 they used focus groups to get the question which was most likely to lead to a "yes" outcome.

It resulted in a 60-40 defeat.

He says: "It is a good example because it is one of the few countries where they have had a referendum on independence which has resulted in a rejection of the proposition.

"Twice, the first time in 1980 and the second time in 1995, both times they had the word agree in the proposition. In both cases they lost the referendum."

So, will the electoral commission accept the SNP wording of the question?

The question for last year's referendum on changing the voting system was changed after it was said it "encourages voters to consider one response more favourably than another".

The original question was to have been: "Do you want the United Kingdom to adopt the "alternative vote" system instead of the current "first-past-the-post" system for electing members of parliament to the House of Commons?"

The Electoral Commission said the phrase, "do you want…to adopt" could imply the alternative vote system was already preferred by some people, or had already been decided on.

And they said the words "instead of" could have suggested there was a problem with first-past-the-post and implied the alternative vote may be better.

It was changed to: "At present, the UK uses the first-past-the-post system to elect MPs to the House of Commons. Should the alternative vote system be used instead?"