Making up lost ground

- Published

Despite comparisons there are big differences between the Spanish and Scottish economies

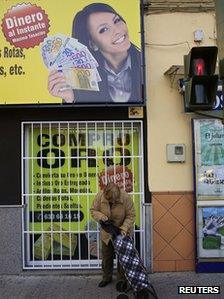

Finding comparisons between the economies of Scotland and Spain makes for alarming reading.

Statistically, Scotland can qualify (where have you heard that before?) as one of the poorest performers of Europe, in that its economic contraction, at more than 4% since the start of the downturn, is similar to that of deeply troubled Spain.

But comparisons by the Item Club of economists are a bit unfair, or at least misleading. There are big differences.

For all its problems, Scotland's banking sector is not in the parlous state of Spain's. Using sterling, it has the escape route of devaluation against its main trading partners. And its unemployment problems are nowhere close to the severe problems afflicting Iberia.

But with three years of contraction out of the past five, the downturn still leaves Scotland with a lot of catching up with the output per head it achieved before 2008, and now looking to 2016 before it does so.

The latest analysis and forecast from the Item Club Scotland points out there are other telling comparisons closer to home.

While Norway and Sweden are held up as examples of small northern nations doing nicely despite wider Europe's problems, Scotland's 4.4% contraction is on the level with Denmark and Finland. The appeal of being Scandinavian is more complex than sometimes presented.

Trendy economics

The rest of the forecast from the Item Club extrapolates from recent data that suggest a divergence between Scotland and the UK.

And it points to a future, for the next four years at least, when Scotland returns to trend growth significantly below that of the UK.

Past growth figures suggested the Scottish economy had ended that long-term trend, and put Scotland around the mid-point of UK performance.

But Item forecasts 0.7% growth for Scotland in 2013 comparing unfavourably with 1.2%. (Note that the Fraser of Allander Institute, that Scotland will see 1.3% growth, ahead of the UK rate of 1.1%.)

The following year, the Item Club forecasts Scottish growth rising to 1.8% and then up to 1.9% for the next two years, while the UK as a whole is back to 2.4% each year.

This matters politically as well as economically. The case for independence has moved from the long-term complaint that Scotland was lagging the rest of the UK to the argument that it could be doing much better than the United Kingdom.

But if this forecast is right, we could see a return to talk of being held back as England's poor relation at least as much as being the next Norway.

Hospitality and hospitals

The Item Club highlights the importance of the large and diverse business services sector in being the main engine of growth, while manufacturing has stagnated and construction remains about 10% below its pre-downturn output.

It highlights the plight of the hospitality sector, which appears to be 9% down on the pre-downturn days over the past three years, while 'accommodation and food' in the UK as a whole is up 2.8% in the past year, and running close to its 2007 levels.

And it warns that the prospects for export-led recovery don't look all that impressive. While conceding holes in the date where oil and finance should be, it says there's a shortfall in export-oriented firms in Scotland.

The analysis also points to one of the curiosities of the growth figures - that output from the public sector is lagging behind the UK.

It's notoriously hard to measure output from across government. But if this data is to be believed, it suggests a lack of reform to Scottish public services is hampering its productivity.

How else to explain the reckoning that output in the health sector in the UK has risen 15% since mid-2008, but in Scotland by only 5%?

Lower levels of immigration, perhaps, but that can't be the whole explanation.

How does it affect real people?

Enough of the sectors and the apparently tiny percentage changes in growth: what does this actually mean for real people?

The easing of inflation in the past few months has helped the second half of this year. Allied to a raised basic income tax threshold and better-than-feared employment figures, Scottish households have 1.3% more disposable income this year.

Cost pressures from fuel, transport and food, plus only modest growth in employment, are expected to slow that to 0.7% next year.

That growth in employment is one of the brighter parts of this picture. Even if it's modest, it does suggest that the private sector will continue to make up for the loss of public sector jobs.

And while all this forecasting assumes the eurozone doesn't implode, and that the US avoids falling off a fiscal cliff, the fear of more shocks to the system are expected to continue weighing on consumer confidence at least until 2014.

The aggregate spend by households in Scotland is reckoned to be down 0.9% during this year, and on track for growth of only 0.4% next year.

It would help, of course, if people had more confidence in the value of their main asset, their home. That's not looking great either.

Small decreases in home prices are expected next year and the year after. Only in 2015 do these forecasters see a modest improvement, by which time house prices, in real terms and in common with England and Wales, will have fallen by a fifth in seven years.

You can also comment or follow Douglas Fraser on Twitter: @BBCDouglasFraser

- Published25 November 2012