How Scotch whisky conquered the world

- Published

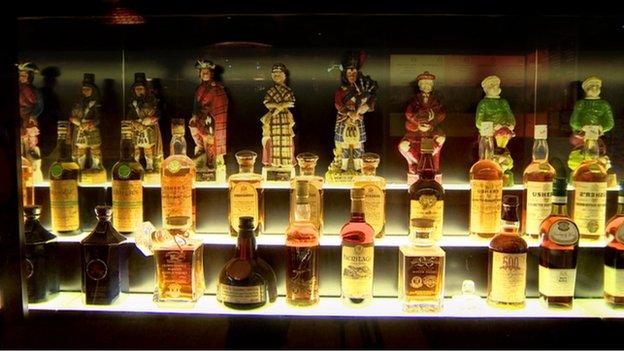

Scotch whisky is a national brand worth toasting. It is a drink that can only be distilled and matured in one country - Scotland - but which sells in to 200 markets around the world. How did Scotch go from cottage industry to global phenomenon and how does it benefit its country of origin?

Scotch whisky is ideally positioned to gain from the growth of the middle class in emerging markets such as Asia, South America and Africa. And for the new clientele it comes packaged in tradition and offers quality provenance.

Gavin Hewitt, chief executive of the Scotch Whisky Association, explains: "We are appealing to the emerging markets. We're appealing to the affluent, the middle-class people who are aspirational, people who see Scotch whisky as the drink of choice.

"They can afford it, and it means they're part of a global network."

Moreover, it works as both a means of celebration and sharing, and (unlike champagne) it's well-suited to drowning one's sorrows when times are not so good.

But while benefiting from globalising markets, it breaks the rules by avoiding worldwide megabrands.

Instead there are thousands of blends, distillery malts, maturation ages and expressions from different types of cask.

Each move up the premium ladder boosts profits.

This is in an industry struggling to distil enough to meet global demand now, let alone its projections of where the market will be within five to 12 years when much of its output will be ready for the market.

Yet there is a question of whether this success story is a result of Scottish success, or down to the world-class marketing strategies of the big distillers?

And there is also a question about who benefits from the success of Scotch?

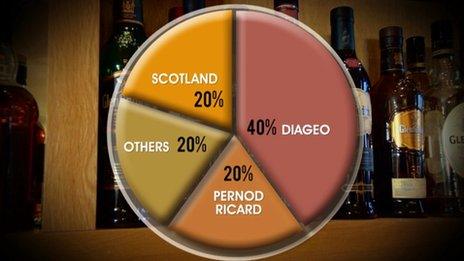

The leading distiller is Diageo, which currently has more than 35% of the market. With its proposed acquisition of a controlling share in India's United Distillers, including Whyte and Mackay, the company is on course to have roughly 40%.

A bit amateurish

How it came to have that dominance is worth recounting.

Alan Gray says the industry used to be run by the 'seat of its pants'

Distillers Company was formed during the inter-war years of the early 20th Century from numerous families which had previously controlled whisky in Scotland, many of them having pioneered exporting to the British empire.

Within Distillers, the different houses competed against each other for business.

Alan Gray, who has been a financial analyst of the whisky industry for more than 40 years and is author of the Scotch Whisky Industry Review, recalls that it was a bit amateurish.

He says: "A lot of the whisky industry in the 1960s and into the 70s was by the seat of their pants.

"They thought 'things are looking good, we'll just produce it, we'll always get rid of it' and, as a result, sometimes there were overhangs of stock in the market.

"That depressed whisky prices which wasn't good for the image.

Ernest Saunders saw the potential of the inefficient whisky giant

"The industry is now much more professional and more commercial, more aware of the need to conserve cash, capital, to use it efficiently and, crucially, marketing also has improved immensely."

In the 1960s, Distillers Company was financially hard hit by diversifying into pharmaceuticals.

It was responsible for the thalidomide drug, intended to combat morning sickness during pregnancy, but which led to numerous physical deformations in babies.

By the 1980s, with growth stalled and distilleries being mothballed, a new breed of businessman had spotted the potential of the industry and of this inefficient giant within it.

USA and France are the biggest markets but Brazil has risen by 48%

One of them was Ernest Saunders, who had been hired by Guinness to rejuvenate the family brewer.

He fought a fierce and bitter takeover battle to get control of Distillers, using tactics that would later land him in jail for one of the most notorious cases of insider trading of the 1980s.

The tactics also included winning the support of Scottish business grandees with a promise that Guinness, along with its new distilling arm, would have its headquarters in Edinburgh.

After winning the battle, the promise was quickly forgotten, and the company that would later be rebranded as Diageo remains headquartered in west London.

Last year, it had profits of £3bn, with a third of its business in whisky.

It owns brands such as Johnnie Walker, which goes worldwide, J&B, with its strength in France, whisky's second biggest market, and Buchanan's and Old Parr for Latin America.

Just 20% of Scotch whisky is made by companies based in Scotland

It can also boast an impressive stable of other spirit brands ranging across Smirnoff Vodka and Gordon's Gin, alongside newer acquisitions that put it in a strong position, with local grain spirits from Vietnam to Turkey.

The other big growth company is Pernod Ricard, which bought much of the Canadian-based Seagrams in 2000. It now has more than 20% of the Scotch whisky market, with brands including Chivas Regal, Ballantine's and Glenlivet.

Although Scotch whisky must be made in Scotland, only about one fifth of the total output is made by distilling companies which are based in Scotland.

These include William Grant & Son, which pioneered the modern malt whisky category through its Glenfiddich brand.

And also the Edrington Group, based in Glasgow, with brands including Famous Grouse, Macallan and Highland Park.

The three sisters who used to own it set up the Robertson Trust to be the beneficiary of Edrington's profits. That trust disperses the funds to charitable causes, mainly in Scotland.

New into the market are smaller distillers. Some saw an opportunity to buy mothballed production with bonded warehouses of stock, and they have seen their investment handsomely rewarded.

That is at least in valuation. It can take a lot of patience to see cash flow.

BenRiach on Speyside is targeting the high-spending consumer

Billy Walker, with two South African investors, bought BenRiach on Speyside with less than £8m. It is now worth about three times that, and his company has bought the Glendronach distillery as well.

He is targeting the high-spending consumer.

Mr Walker says: "There's a market out there that's very interested in the top end and, frankly, pricing is not an issue. It is availability and having something different and something special."

With single malts increasingly differentiated through maturation in sherry and Madeira casks, prices can reach into hundreds of pounds.

Mr Walker says: "We have to have 12-year old expressions, but we have to be outside that."

"That's a very cluttered area. We try to create expressions - 16, 20, 25-year olds - that take us out of the clutter."

Companies such as BenRiach are thriving in the slipstream of big players such as Diageo, with their marketing push.

Diageo opened the Roseisle distillery three years ago

For all the dominance of the big players, and control of the industry from headquarters outside Scotland, there's a recognition that - for now, at least - everyone in whisky is winning from its growth.

And there's a lot more to come, not least if India, the world's biggest whisky market, lowers its 150% tariff barriers.

That is why the big distillers are also continuing to invest.

Only three years after opening Roseisle, near Elgin in Moray, with capacity to produce 10 million litres of spirit each year, Diageo has announced a five-year plan which includes the building of at least one more on that scale, while it expands other distillery capacity.

According to the SWA's Gavin Hewitt: "We have already enjoyed more than £1bn of investment into Scotland in the past four years.

"I will put my head on the block now and say that we're going to enjoy £2bn of investment into the Scotch whisky industry in the next three to four years".

- Published9 January 2013

- Published9 January 2013