Migration masala

- Published

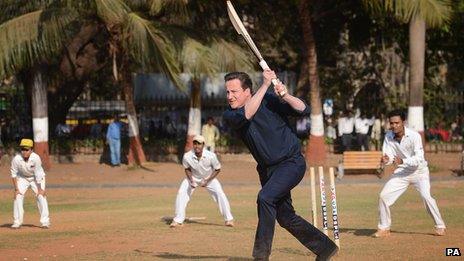

David Cameron is not the only leader whose been batting for his country in India

David Cameron has grabbed the headlines in India, with a pledge of no limit to visas for genuine students coming from India to British universities.

He's also added spice to the mix by saying there will be a fast-track process for Indian business-people wanting to visit Britain.

While telling India that it's going to be a great power this century, and before too long, that can make front page news in the Delhi and Mumbai press.

His main competition for column inches has been a corruption scandal involving a military deal to buy Somerset-made helicopters from an Italian company.

That tells you quite a bit about doing business with Indians. It's worth flattering them as a rising global power: globalisation to India means access for people but this remains a country that, to put it politely, lacks transparency.

Delhi daily deals

UK plc is not the only national effort dedicated to cracking open the huge Indian market. President Hollande has just left, having said much the same as David Cameron, but in a charming French accent.

Other economic powers are paying homage at the Delhi government and Mumbai stock market, though rather less so China, which lurks in the background of David Cameron's talks in New Delhi today about cyber-security.

Indian firm HERO has sold Scotland's biggest call centre business after running it for the past six years

The visit has brought forth a whole bunch of deals including 13 new Intercontinental hotels being built in India.

BP used the access to talk about its biggest gas field. There's infrastructure, education and healthcare to be sold, as well as the English Premier League in football, while Indian companies invest further in England and Northern Ireland.

Today's news about Indian investment in Scotland today was about the reverse.

HERO is a giant bicycle-maker in India which has owned Scotland's biggest call centre business for the past six years.

It employs 3,000 people from Falkirk to Rothesay and Dunoon, plus 3,000 more in England, but HERO has sold it for nearly £80m to a French-based rival backed by Charterhouse private equity funds.

Glacial pace

Behind all this remains the prize of a free trade deal between India and the European Union.

It's six years since talks started on that, and they've ground close to a halt. The internal politics of India have made it hard to get to a deal.

But a slowing of its rapid growth rate and concerns at sharp declines in foreign investment have focused minds and kept talks going.

In Brussels, the hope is that last week's announcement that free trade talks are soon to open between the EU and US will give some impetus and urgency to the glacial pace of talks with Delhi.

A cut to 150% duty on imported distilled spirit, notably including Scotch whisky, is already all but agreed. That faced much resistance from India's distillers, and may still protect them at the cheaper end of the market.

Automotive parts has also been a sticking point, but is less so now. India struggled with internal opposition to opening the "multi-brand retail" or supermarket sector to companies such as Tesco and Walmart. Recently, it resolved to do so. There remain problems around opening up business and financial services.

Playing the visa card

And there remains the challenge of visas. David Cameron had to say something about opening up, because it matters a lot to Indians.

But the movement on visa and short-term business access did not address the UK government's opposition to allowing access to Indian professional and technical staff.

Indian negotiators want them to have temporary work rights inside the European Union, often to back up contracts won with European clients by business services and software firms.

Known as Mode 4, this is being watched closely by campaigners against migration in Britain. And while the negotiators are European, they know the main obstacle to allowing that comes from the London government.

While in India, David Cameron has to be mindful of the pressure he faces on migration back home, and the pledges made before the last election.

Business does not like the political pressure to restrict flow of skilled workers, and it's told the prime minister as much.

The tourism industry is also raising the problems of Britain requiring a separate visa of Asian tourists, meaning their European tours have a habit of shunning the UK.

So Mr Cameron will also be mindful that India views the UK as a bridgehead into the European market. And if he's looking for investment, it may not help to have signalled that he's heading towards a referendum which could see Britain leaving.

You can also comment or follow Douglas Fraser on Twitter: @BBCDouglsFraser