How can Scotland's town centres survive?

- Published

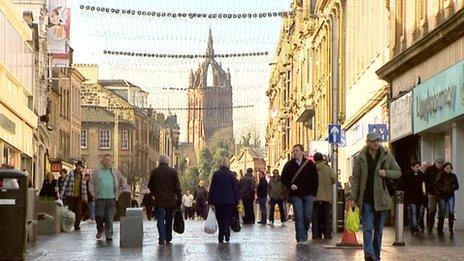

Paisley is considering bringing back traffic to its pedestrian shopping street

Shops in Scotland are said to be closing at the rate of almost one a day and fewer new stores are opening. How are towns trying to turn things around?

With the sun streaming in through the windows of a bright shop and studio in the Ayrshire town of West Kilbride, a textile designer and maker is hard at work on pieces such as personalised fabric hearts for Mother's Day.

She is surrounded by things at various stages of completion, different materials, ribbons and vividly-coloured buttons in sweetie jars.

Back in 1998, 21 out of the 40 premises were boarded up and the community decided it wanted to try to halt the slide. The result was the branding of West Kilbride as Craft Town Scotland.

Textile designer Lorna Reid first came here because she wanted to live and work in a place with "like-minded people".

"It's a busy street", she says.

"There's lots going on: nursery pick-up time, school drop-off time. Lots of people walking past and people do come and visit us specifically and I have local people come in and say 'can you make this for this specific occasion?'.

"I think the fact that we're all together under one brand is extremely important," she adds.

West Kilbride has branded itself as Craft Town Scotland

The town's population is just under 5,000 and many people commute, so they are not there to use shops and other facilities during the day.

There are now nine craft studios up and running with the idea that they act as anchors which will draw in other businesses.

"We are consistently used as an exemplar of genuine bottom-up community-led regeneration," says Maggie Broadley, director of Craft Town Scotland.

A community which saw that its town centre had a problem, knew that it could not compete with out-of-town shopping and then tried to offer something unique.

Changing massively

She talks about "knock on effects" in the wider area and "people valuing where they live, feeling proud of their achievements".

So with shopping and leisure habits changing massively how could town centres across Scotland deal with that better?

Last year the Scottish government launched its National Review of Town Centres, chaired by architect Malcolm Fraser.

He says we need to recognise the importance of town centres "in economic terms, in cultural terms, in low carbon terms," but also look at why they are "underperforming".

Fraser says: "Personally I think we've lived in a post-war dream of the future as being stuck in a dumb metal box, driving from suburb to business park, to retail park, to leisure park and home again.

"We thought that that was convenient and modern and clean and it has turned out to be a bit of a disaster.

"Actually I think the future turns out to be something a little more backward-looking actually, a little bit more about community and walking to places and shops on the street and friends on the street and that sort of thing. That's the future."

Across Scotland towns are reconsidering the way ahead.

Paisley, for instance, has struggled to compete against the draw of Glasgow and the out-of-town centres and suffered from shop closures.

Now there is a proposal to allow cars back into a pedestrian zone in the centre of town at certain times of day.

Renfrewshire Council leader Mark Macmillan says it is about having the "best of both worlds".

But what does a random sample of local shoppers make of the idea?

"They said it would bring more people into the town for shops -- we haven't got shops," says one woman.

"It's not what you would call a town now."

Local branding

But another woman hurrying down the street with bags over her arm thinks the idea might just work.

"Will it bring it (the town centre) back to life? I don't know because a lot of people aren't willing to open up shops nowadays but it can't do it any more harm than it's already done," she says.

Clarkston has formed a business improvment district

On the outskirts of Glasgow lies the suburb of Clarkston. Since 2010 it has been a Business Improvement District, one of 18 in operation across Scotland.

The idea, which started in Canada, is to get local businesses to decide what they need to improve their own area. They then vote on whether to go ahead with the plan and contribute towards funding it.

In Clarkston they have introduced local branding, with banners and benches, Christmas lights and community events.

"It's not a case of the businesses saying here we are, come in," explains Debra Clapham, a local solicitor who is chair of Clarkston Business Improvement District.

"What we've got to see is what does the community want from the businesses? What will make them shop here as opposed to going to one of the other shopping centres? What is relevant to the businesses? What is relevant to the community? And we've got to try and marry them up.

"I think it's beginning to work but it's a slow process."

Out-of-town centres

So what might be the wider solutions?

Malcolm Fraser points to things such as measures to get people to live in town centres again, to keep schools and other services there and to have a mix of retail along with culture and leisure. He remains optimistic.

"I've been told that out-of-town retail means that town centres will die," he says.

"I've been told that the internet means that bricks and mortar retail will die. I remember not so long ago that video and DVDs would mean that cinemas would die.

"People like to leave their houses. We are social animals and that's what town centres offer.

"They do need some assistance and they do need us to get rid of outdated thinking which sees them as things of the past, but they will survive."