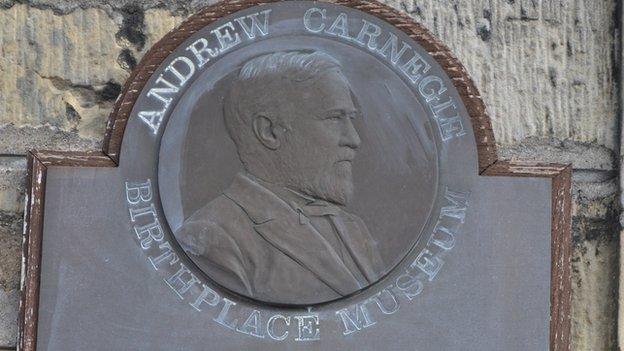

Andrew Carnegie: The man who gave it all away

- Published

Andrew Carnegie became one of the world's greatest philanthropists

The name Carnegie is ubiquitous; libraries, institutes, trusts, foundations in Britain, the United States and Europe established by the Scottish-American steel baron turned philanthropist, Andrew Carnegie.

The Carnegie UK Trust is marking its centenary this year. So what kind of man was Andrew Carnegie and what is his legacy?

"The story of a penniless Scot going over to America and becoming the richest man in the world would be an amazing story in and of itself," says Scots entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sir Tom Hunter, who describes Andrew Carnegie as one of his heroes.

"But then for Carnegie to actually take his wealth and think about it and actually do so much good with his wealth, it takes it to a different level as far as I'm concerned."

The Carnegie story began in mid-nineteenth century Dunfermline where his father was a handloom weaver of linen. The family lived in one room, box beds on one side, cooking on an open fire.

But it was a precarious living and as the weaving industry changed the family decided to emigrate to the United States, borrowing money from family for the fare.

Carnegie was born in a small cottage in Dunfermline

"It was a pretty horrendous journey," explains Angus Hogg, chair of the Carnegie UK Trust.

"But apparently Andrew Carnegie was one of the few who didn't suffer from sea-sickness on the journey, so starting to show his entrepreneurial skills, he started to pick up jobs on-board ship, which bought them little favours in terms of their accommodation and their food and so on."

After they arrived in America, Andrew Carnegie, aged 13, started out as a bobbin boy in a textile mill, and became a telegraph operator.

Later, he was involved in the railroads, organising transport and communications during the American civil war.

He then amassed enormous wealth building up a steel business.

When he sold his Carnegie Steel Company in the early 1900s he got $480m for it and used the money for his philanthropic career.

"It came from social values rather than religious values," says Eric Homberger, emeritus professor at the University of East Anglia.

He remembers the Carnegie library in his hometown in New Jersey, one of the few opportunities for cultural enrichment which existed there.

"Many of his (Carnegie's) biographers trace it back to the experience of having been the son of a Scottish weaver, who absorbed from that family a set of values; a belief in democracy and a belief in a 'society that provides opportunities for everyone' and not just the super-rich.

A statue of Carnegie sits in the park that he gave to the people of Dunfermline

"So we can't say the moment it began but I think we can trace its source back to Scotland."

Andrew Carnegie wrote prolifically about wealth and what to do with it, famously writing that the "man who dies...rich, dies disgraced".

Sir Tom Hunter says: "When I was doing my thinking about what to do with wealth, I went to New York and I visited the Carnegie Corporation of New York and went in to see the president, a gentleman called Vartan Gregorian.

"He's probably my philanthropic mentor and Vartan basically challenged me to say the money wasn't really mine."

He laughs as he admits that was quite a challenge to do.

"And to do some good while you're still here, don't be the richest man in the graveyard, which certainly resonated with me."

And when Andrew Carnegie became extremely wealthy, Scotland and more specifically Dunfermline was one of the first to benefit.

Urban park

Through ornate gates which commemorate Carnegie's wife, Louise, a path leads into the Fife town's Pittencrieff Park and up towards a statue of the philanthropist himself.

It may be a bitterly cold day but there are still children playing on the swings, while other people are walking their dogs.

When Andrew Carnegie was a boy this was a privately-owned estate, just a short distance from the family cottage and he was regularly turfed out by the gamekeepers.

The 80-acre urban park became his first benefaction to the people of Dunfermline. The town has benefitted in other ways too, including the library, the swimming pool and its own Carnegie hall.

A trust he set up to benefit the town called on the trustees, in the parlance of the time, to "bring sweetness and light to the toiling masses".

"He was a very generous man," says one man walking down the main shopping street, which, like many in Scotland has its fair share of empty shops.

"He also helped to develop the Dunfermline area and had a focus on children and education."

Public criticism

Most people on the street, talk about the glen, which is what locals call Pittencrieff Park, although one woman comments wryly that Carnegie would "have a fit" if he saw the state of Dunfermline now.

"But all the things he gave us are still here," interrupts another.

Yet how was all this money amassed? Andrew Carnegie was operating in a ruthlessly competitive age and he was a tough employer.

A bitter strike at Homestead Steel Works in 1892 brought public criticism, although Carnegie was not actually in the country at the time.

"He's a man of intense paradoxes," says Eric Homberger.

"He did so much good and yet he embodied in his own industrial activity so much that was, well, take your choice about how to describe it, but I regard it as highly deplorable.

"He was a plutocrat, but also a philanthropist. He was very sceptical about the social desirability of speculation, but he was one who profited immensely from the speculation that he himself made.

"So everywhere you turn looking at this man's career you find puzzles and paradoxes. It defies our desire to have a white hat guy, a hero, a virtuous man.

"He was virtuous, but he was also some other things as well and it makes for an interesting story that he wasn't all good or all bad, but like most of us, pretty much a mixed bag."

Many of the philanthropic trusts which Carnegie set up, already have, or are about to go through, their centenary. The Carnegie UK Trust for instance is marking its 100th year.

In the past century it has been involved in a diverse range of programmes, including establishing something like 660 libraries, as well as projects involving the arts and sport. It now concentrates on issues of public policy.

"If you consider that by his death in 1919 he had given away to the foundations $350m, that's just an incredible sum of money," says Angus Hogg.

"We're still there working and looking towards the next 100 years. I don't think you'd find anything else in the world that equates to that."