Ice Man: Edinburgh GP Gavin Francis on his year at the bottom of the world

- Published

At the Halley Research Station there is 24-hour darkness for 105 days during winter

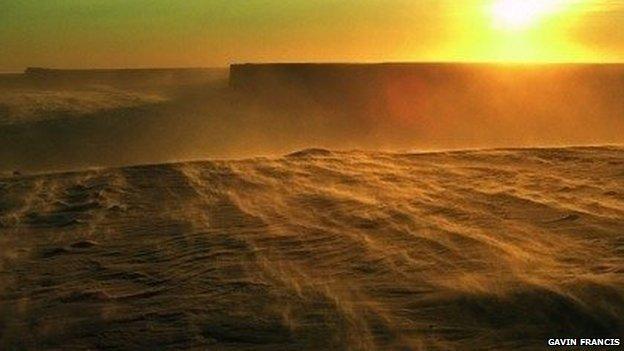

Life at the south pole is harsh. There is darkness for four months of the year. Temperatures reach minus 60 degrees Celsius. Wind speeds get up to 150 miles per hour.

So how did Dr Gavin Francis, an Edinburgh GP who spent a year as the resident doctor at the Halley Research Station in Antarctica, cope in such an inhospitable place?

"Lots of hot chocolate," he said.

There have been six Halley bases built so far: the first four were buried by snow accumulation and crushed until they were uninhabitable

"And a comfy bed to sleep in at night…when you're not sleeping out in a tent on the ice of course."

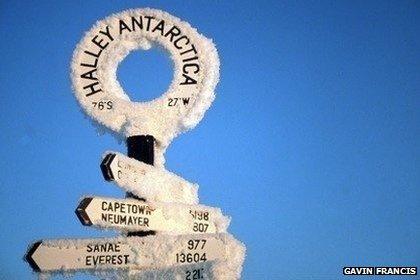

The base, which is run by the British Antarctic Survey, lies at 75 degrees south, 100 miles from the south pole.

It is so remote that it is said it would be easier to rescue someone from the International Space Station.

After the sea freezes over in March, no-one can get in or out. You are stuck there until the next summer.

Dr Francis told BBC Scotland's Stark Talk: "It does feel like an underworld when you're there, it does feel like a parallel universe.

"There is this wonderful perspective you can get in the Antarctic, because it's so different from anywhere else.

"There is nothing human-sized at all. Everything is either tiny like snow crystals, or vast like auroras, the planets moving, stars, meteor showers, glaciers.

"To be a human being in that environment is extremely alien, but it is also quite magical in the sense of giving you a perspective of what the rest of the universe is really like."

Taste for adventure

Dr Francis was born in Fife in 1975, and says that growing up he had a fascination with how the world fitted together.

He spent an idyllic childhood exploring the woods around his home.

At the age of seven, he remembers finding a dead rat and asking his parents if he could be allowed to boil it.

"It seemed to me the natural thing to want to do. Boil the flesh off so you could get the skeleton.

"I built a fire in the field and got an old cracked pan and did it outside."

Later in Antarctica, it was a penguin that he was told he was not allowed to dissect.

"It had fallen over incubating its eggs, and it seemed the natural thing to me, as a doctor and as a naturalist, to cut it open and see how it died.

"I don't think the British Antarctic Survey were too happy with that."

After studying medicine at Edinburgh University, and medical training jobs "where you're working 100 hours a week and you've got a lot of chaos and blood and death to deal with", Dr Francis worked in A&E at the old Royal Edinburgh Hospital.

Cabin Fever

At the Halley base, his job was to look after the health of the team of fourteen people stationed there.

"In such a small community when everyone is fit and well, you are called upon to be a doctor almost never," he said.

"I did use my medical skills, but it was always for fairly minor things - tooth fillings, x-rays of broken bones, people with general aches and pains, skin rashes.

"Every two or three years something terrible happens in the Antarctic, something really horrible, and they are always really glad they have someone there.

"I was there in case somebody injured themselves really badly - fell into a crevasse, or injured themselves with crampons, or got bitten by a seal."

Exploring a crevasse: the Antarctic covers an area of almost 14 million sq km and contains 30 million cubed km of ice

The wintering team at Halley includes a chef, a doctor, mechanics, an electrician, several electronics engineers and a heating and ventilation engineer

One of the reasons for the location of Halley is that it is under the auroral oval, resulting in frequent displays of the Aurora Australis overhead

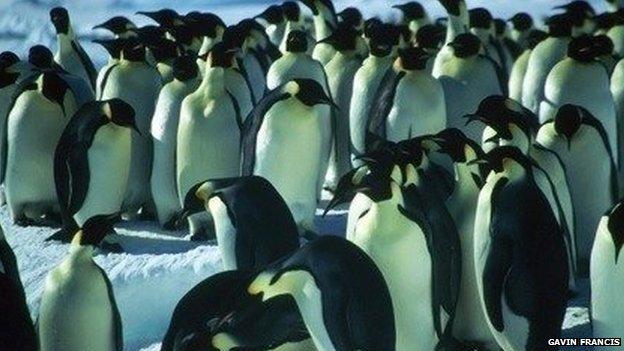

The Emperor penguin is the world's largest penguin, and lays its single egg during the coldest time of the year, when temperatures drop to as low as minus 60 C

Spin drift over a cliff edge: winds in the Antarctic reach velocities of up to 112 miles per hour (images copyright of Gavin Francis)

With time to spare, Dr Francis found other ways to occupy himself at the base.

"You have to be part of the base community," he said.

"That means chatting in the bar, preparing meals, doing the thousands of jobs that need doing every day on an Antarctic base, such as refuelling the generators.

"We would go out and do communal exercise every day, and I think that helped.

"It was cold. But by then you are pretty used to it. And digging that amount of snow heats you up pretty quick."

But the extreme environment was not the only challenge. Sharing a small space with fourteen strangers could also take its toll.

"There's times when everybody gets rubbed up the wrong way, but there is enough opportunity to go and spend some time on your own.

"I was very lucky with my team, we all got on very very well in the end."

"It wasn't about the big brother style dynamics of fourteen people in a portacabin.

"For me going to the Antarctic was all about the austere beauty of the place.

"I had a window that looked out over the ice.

"I think having big windows that looked out onto it meant that I was able to keep hold of where I was, that I wasn't just locked into a little box with these strangers."

Halley was founded in 1956 by an expedition from the Royal Society, and named after the astronomer Edmond Halley

One of the things he missed most of all was smells.

"There are no smells in the Antarctic," he said.

"When I was coming back to the north, sailing back to the Falklands after 14 months away, one of the first things I noticed was the smell of grass a day before we got there.

"My sense of smell had become so acute, and I missed the smell of greenery so much."

So, would Dr Francis, who has written a book about his experiences, Empire Antarctica, return to the Antarctic?

"I never thought it was a stupid decision [to go]. I sometimes wondered whether I had bitten off more than I could chew," he said.

"I would like to go back... I don't think I would winter again though."

- Published6 February 2013