Scotland the brand: How important is where a product is made?

- Published

Dunlop cheese originated on a farm near the Ayrshire town

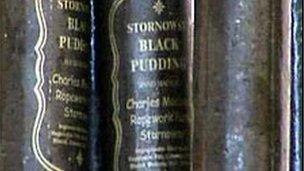

New European protection means that Stornoway's famous black pudding can only be made in the Hebridean town or its immediate area. So how important is place in developing a brand?

On a farm just outside the Ayrshire village of Dunlop, a small herd of traditional Ayrshire cows is gathered in a yard, impatiently waiting to be milked.

"The Dunlop's got a tremendous history behind it," says farmer Ann Dorward as she calls out to the cows to come over to her.

She says: "The Ayrshire cow was first bred in this area and the Dunlop cheese originated on a farm just a mile up the road.

"This cheese was far superior to what they had been making because they used the whole milk rather than the skimmed milk."

The Dunlop cheese was first produced in this area in the late 17th century but in the years since, it has become widespread and the name is now generic.

Stornoway black pudding can only be made around the Lewis town

Yet efforts are under way to protect the name 'traditional Ayrshire Dunlop' as something which would reflect local character, traditions and the flavour of the milk.

"What the cows are grazing on and the environment they're kept in is then giving the milk its character, which is then going on into the cheese," says Mrs Dorward.

If they are successful in getting EU protected food name status, she says she believes it would be good for the local area.

"People will think, oh where is Dunlop? I've heard about that cheese and, just hopefully, it would bring some business to the area."

The European Commission's Protected Geographical Indication for Stornoway black pudding means it has now joined a list of food names which enjoy different kinds of EU protection - the Cornish pasty, Arbroath smokies, champagne and many others.

But how important is geography when it comes to food?

"If, for example, with pork pies, the area in Leicestershire where they make Melton Mowbray pies has protected status, is that saying that they make a better pie than someone in Norfolk or someone in Cornwall?" asks Daily Telegraph food writer Rose Prince.

What is special about a Melton Mowbray pie?

"Because I don't think it does, I don't think it actually has any meaning."

On a wider scale, around the world, countries brand themselves too.

Italy for instance, despite any other problems it might have, remains synonymous with style, while New Zealand has the great outdoors.

2014 is shaping up to be a busy year in Scotland; the Commonwealth Games, the Ryder Cup and the independence referendum.

"There is potential when big events are on to use that as a springboard to help develop the brand of the country," says Alan Wilson, professor of marketing at the University of Strathclyde Business School.

He argues that such events inevitably raise a county's profile.

"People are looking for the quality aspect," he continues.

"So Scotland has a lot of quality in its products and services that it can build on and they're also looking for natural products, natural activities, natural landscapes have become very attractive to people and if we can build that into our brand, that becomes quite important."

Prof Wilson says food and drink, be it Stornoway black pudding or whisky, tie into that, but it can also cover other things such as the renewables sector, bio-technology and computer games.

In the Paisley museum, an old Jacquard loom is worked as it would have been in the 19th century when Paisley shawls formed a huge part of the town's prosperity.

The Paisley Pattern did not originate inn the Scottish town

A foot pedal operates one part, then the shuttle is shot through by hand.

Yet the story of those shawls and their patterns are proof that product and place can be a complicated story.

The patterns did not originate here, and the shawls themselves were originally called Indian imitation shawls.

Yet they became associated with the town, not least through the emerging journalism of the time which profiled the industry.

Indian shawl

Now of course they are something to be found all over the world.

Ann Dorward thinks Dunlop should get protected name status

"There were two places in Scotland that did it, Edinburgh and Paisley," explains Dan Coughlin, the curator of textiles in Paisley museum.

"Edinburgh finished weaving shawls about 1847, so the only place then in Scotland producing shawls would have been Paisley and it became synonymous with the imitation Indian shawl.

"Then in the English-speaking world the name changed from imitation Indian, to Paisley.

"We have collections of shawls which we call the Paisley shawls, but some of them might have been produced in Norwich and some of them might have been produced in Edinburgh, we have no way of knowing because they're so similar."

Back at West Clerkland farm in Ayrshire and in one of the sheds, young kids are jumping about in their pens. They are intensely curious as a stranger approaches. The goats here are also milked and the milk made into cheese.

Ann Dorward says trying to get traditional Ayrshire Dunlop recognised is part of a local food story.

She says: "It just adds to the growing thoughts on where your food comes from and what you're eating.

"I've seen a big change over the past 30 years in people's attitudes about what they're eating and where their food has come from and even with the sheep and goats cheeses, they're more the norm now rather than something which was looked upon as being a little bit unusual, which is nice."