Why did Nelson Mandela thank Glasgow?

- Published

Nelson Mandela thanks the people of Glasgow for their support during his imprisonment.

Twenty-five years ago Nelson Mandela, a short time after his release from three decades in prison, came to Glasgow to praise the people of Scotland's biggest city.

A decade earlier when many others were still condemning him as a terrorist for his role in challenging the system of racial segregation in South Africa , the "Citizens of Glasgow" had been the first to offer Mandela the Freedom of the City.

In a speech at the City Chambers in Glasgow on 9 October 1993, he said: "While we were physically denied our freedom in the country of our birth, a city 6,000 miles away, and as renowned as Glasgow, refused to accept the legitimacy of the apartheid system, and declared us to be free."

Mandela's visit to Glasgow in 1993, the year before he became president of the Republic of South Africa, was the culmination of a long association between people in the city and his campaign for freedom, which began when he was imprisoned in 1962.

Scottish anti-apartheid activist Brian Filling campaigned from the 1960s against the system in South Africa which allowed the white minority to oppress the majority black inhabitants.

He had joined the campaign when his parents got to know the English theatre director Cecil Williams, who had allowed Mandela to pretend to be his chauffeur and had been in the car with him when he was arrested.

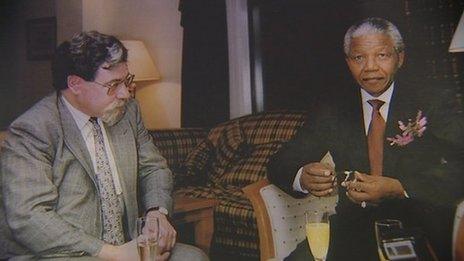

Brian Filling arranged for Nelson Mandela to visit Glasgow

Mandela had been convicted of charges including conspiring to commit acts of sabotage and guerrilla warfare for the purpose of violent revolution.

However, the trial was condemned by the United Nations Security Council and nations around the world.

Mr Filling says that, despite some of the dreadful things happening in South Africa in 1960s and 70s, it was "not fashionable to be associated with Mandela because he was widely regarded and reported in our media as a terrorist".

However in 1981, Glasgow Council decided to set its face against this opinion and awarded Mandela the Freedom of the City.

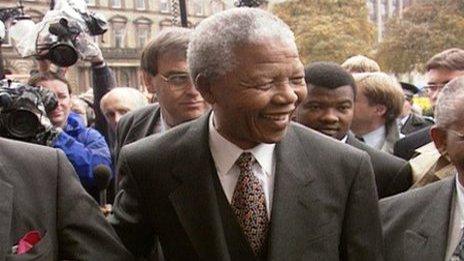

Mandela smiles as he arrives at Glasgow City Chambers in 1993

Mr Filling remembers that just a couple of years earlier the previous Lord Provost of Glasgow, David Hodge, had hosted a lunch with the South African ambassador, which had sparked a protest outside the City Chambers and a threat by catering staff not to prepare the food.

He says: "The incoming Lord Provost, Michael Kelly, partly as a reaction to all this, wanted to give the freedom of the city to Nelson Mandela."

Dr Kelly told the BBC: "It was a bold step for the Labour Party in Glasgow because Mandela was regarded as a terrorist by a lot of people and many people thought Glasgow should not become involved in this at all.

"So it was an uphill struggle and we received a lot of bad publicity, but eventually when Mandela's story got through people began to see that we and he were in the right."

Glasgow's promotion of Mandela's cause quickly led to other cities following suit and within a year Kelly had launched a declaration for the release of Nelson Mandela. It went on to gain support from 2,500 mayors from 56 countries around the world.

The declaration got the backing of the United Nations in New York and Dr Kelly, on behalf of the city of Glasgow, had the "privilege" of being invited to speak first in support of the petition.

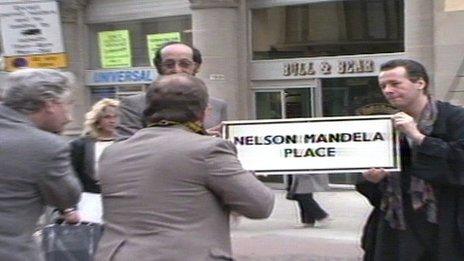

Simple Minds singer Jim Kerr supported renaming a city centre square

In 1986, Glasgow brought more attention to the jailed freedom fighter by changing the name of St George's Place in the city centre to Nelson Mandela Place.

The name change was made more significant by the fact that the South African consulate-general was based on the fifth floor of the Stock Exchange building, at an address which now bore the name of the country's most famous political prisoner.

By now the efforts to free Mandela had become mainstream with global pop stars such as Jim Kerr, from Glasgow band Simple Minds, writing songs and playing concerts in support of his freedom.

International pressure, in the form of sanctions against the South African regime, eventually led to Mandela's release.

At the age of 71, Mandela was freed on 11 February 1990 after 27 years in prison.

During the 1980s he had been given the Freedom of the City by nine UK regions - Aberdeen, Dundee, Greenwich, Islwyn in Gwent, Kingston Upon Hull, Midlothian, Newcastle, Sheffield and, of course, Glasgow.

'A special place'

It was the city which was chosen to host Mandela as he arrived to accept all these awards in October 1993.

Brian Filling, who set up the 1993 trip and spent two years getting agreement from all the other cities that Glasgow should be the venue, says: "He was very appreciative of the people of Britain for their support, rather than the government - which seemed to hold out against imposing sanctions on South Africa.

"I think there is a special place in terms of his heart and mind for the people of Scotland."

Dr Kelly was able to ask Mandela if he knew about Glasgow awarding him the freedom of the city back in 1981, while he was locked up on Robben Island.

The former lord provost says: "He confirmed there was a grapevine and through that he'd received these snippets of information. So at the time he had known about the award, and it kept him and his fellow prisoners going."

Mr Filling says there had always been a concern about whether the man he had campaigned to free for so many years would live up to the "legend".

"But in fact, he did. If anything, he was even greater than he had been imagined."