Glasgow's bubonic plague outbreak in 1900

- Published

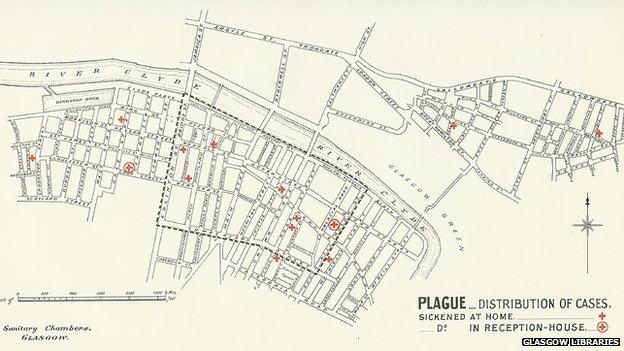

Map showing the distribution of plague cases in Glasgow in 1900

The words bubonic plague may sound like something from the Middle Ages but it was reported recently that a teenager in Kyrgyzstan had died of the disease - the first case in the country for 30 years. Yet within touching distance of the present day, Glasgow dealt with its own small outbreak of bubonic plague, in 1900.

"There were calls for disinfecting all the trams, all the ferries, even all the coins which are in people's pockets in case they should carry some kind of contagion," says Dr Clifford Williamson, a history lecturer at Bath Spa University, who has studied the Glasgow outbreak.

It was part of what was known as the third pandemic. During this phase, the plague was found in places including China, Hong Kong, Madagascar, Hawaii, Australia, San Francisco, Portugal and Glasgow.

In early August 1900, there was a series of deaths in the city which were initially attributed to typhoid but some of the symptoms perplexed one of the doctors involved and on further investigation it was discovered that they were suffering from bubonic plague. How it spread was disputed.

"The first, (version) and this is promoted by the Local Government Board for Scotland in its report in 1901," explains Dr Williamson "was that foreign sailors who frequented brothels in the city were passing on the disease through some kind of physical contact.

"However the city of Glasgow's own public health department, when it dissected rats which were captured in the area where the disease was prevalent, noticed that a considerable number of them were infected by the disease and the disease is carried by fleas."

The plague was first seen in people living in the densely-populated area of the Gorbals. At the time, a part of the city which had many other problems.

"It would have been a very busy area, a very overcrowded area," says Fiona Hayes, the curator of social history for Glasgow Life.

"It would be a poor area as well generally and you'd find very cramped conditions, very poor or non-existent sanitation, conditions in which disease, particularly communicable disease, would thrive."

Glasgow's response to the plague had different elements.

Rat catchers were sent out in large numbers in an effort to reduce the vermin population, while with the agreement of the Catholic Church, there was also a temporary suspension of wakes, as it was believed that gatherings of people could be implicated in the spread the disease.

In the end, something like 36 cases were identified and 16 people died.

This was before the National Health Service, but since the 1880s the Corporation of Glasgow had offered health care to those infected with diseases deemed as potentially dangerous. The city had a very comprehensive infrastructure for dealing with infectious disease.

"This is no accident," says Dr Williamson, "every year there are around 15,000 fatalities from infectious diseases in Glasgow in this particular period.

"It had a hospital service very clearly pointed towards how to deal with the outbreaks of infectious diseases but it also got a massive stroke of luck because very early on, the disease was identified when there might only have been five or six cases, rather than, as was the case with other places, when it was into the hundreds. "

Yet although this third plague pandemic did ultimately spread to countries across the globe, there are those who argue that the way it did that was very different to, for instance, the Black Death in the Middle Ages.

Completely different

"Black Death was a very efficient disease that spread person to person, extraordinarily fast," argues Sam Cohn, professor of Medieval History at Glasgow University.

"It circumnavigated almost all of Europe, in three years, without the railways, without the motor car, on the other hand this bubonic plague of the 20th century spreads extraordinarily slowly because of the rat.

"Rats are homely critters, they don't like moving very fast or very far. It's a different disease, whether it's a completely different pathogen is another question."

The 1900 outbreak had economic as well as health effects.

Historically the River Clyde and overseas trade have been crucial to Glasgow's prosperity. But during the period of the plague outbreak some ships coming from Glasgow to ports around the world were held to be investigated before being allowed to dock.

"Here you have this disease from Central Asia, arriving on the steps of Scotland through trade," says Robert Perrins, Dean of the Faculty of Arts at Acadia University, Nova Scotia in Canada.

He is interested in the Glasgow outbreak because, although the numbers are small, he says it demonstrates the interconnectedness of the modern world.

"In some ways this is similar to the Sars outbreak about a decade ago, where you had people moving this disease which had originated in China, then Hong Kong to places like Canada. So I think it's a good example of how everyone in the world should be aware of outbreaks of disease and how disease can spread with modern, mass transportation."