Aircraft Lidar illuminate Scotland’s past

- Published

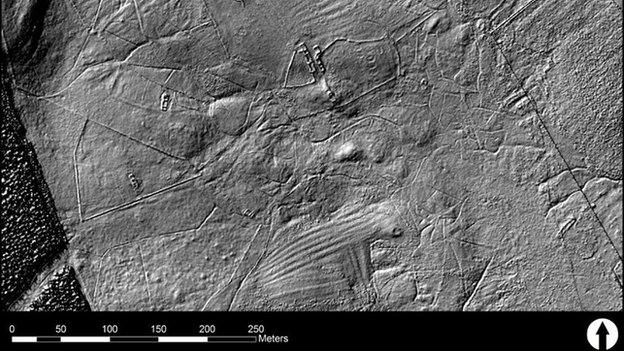

Airborne laser scanning was used to take this image of Broubster in Caithness

For thousands of years, people have left their mark on Scotland's landscape. But time and vegetation have made many of those marks difficult or impossible to see.

Now that is changing radically. The Royal Commission for the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS), working with the professional consultancy AOC Archaeology Group, are using a technique called airborne laser scanning.

It uses an aircraft fitted with Lidar. Think radar, but using a laser instead of radio waves. The laser scans the landscape and data from the reflected light is stored and analysed.

The result is a 3D computer map of the past.

In the past, aerial surveys had to hope for the sun being in the right quarter - and a dry summer - before the landscape would give up its secrets.

Different angles

Now Graeme Cavers, project manager with AOC Archaeology, is making the landscape turn in three dimensions on a computer screen.

It gives us a view of Scotland never seen before.

"Once it's in the software we can rotate the data," he said.

"We can move it around the screen and look at it from different angles.

"But also - perhaps more importantly - we can light it from different angles and accentuate micro-topographic features and pull out things like archaeological features we haven't been able to see in any other way."

Lidar has been around for about 50 years, aerial surveys even longer. But putting the two together to look for archaeological sites is a new departure.

Dave Cowley, aerial survey manager for RCAHMS, says it's almost impossible to overstate the significance of the technology for the future of archaeology.

The technique puts together aerial photography and airborne laser scanning

"'Revolutionary' is an overused word," he said. "But the way to think about where we are with Lidar today is how, a hundred years ago, aerial photography might have been regarded.

"We take it as routine the view from above that aerial photography now gives us."

One particularly arresting image is a laser scan of Broubster in Caithness. A single frame lays bare millennia of human settlement. A physical history of Scotland stretching back to before it was Scotland.

"It is absolutely stunning," said Mr Cowley.

"We're probably seeing 4,000 to 5,000 years of superimposed activity.

"People have been living, farming, dying, burying people in this landscape."

And now we can see it for the first time.

Unknown sites

Airborne laser scanning has already created a buzz in the international archaeology community. That's why a gaggle of experts is gathering in Edinburgh to discuss the implications of the technique.

They'll hear of initiatives elsewhere in Europe, including an ambitious project to survey Germany's third-largest state. Baden-Württemberg is one-seventh the size of the UK and the work will take about six years. Without Lidar it would take decades.

Both RCAHMS and AOC Archaeology say this does not spell the end of traditional trench archaeology. People will still be needed to wield trowels and brushes and get their knees dirty.

Not least because it seems every flight uncovers hitherto unknown sites.

"It is one of those things we're going to look back on in 20, 30 years' time, and wonder how we ever managed without it," said Mr Cowley.

One final note of reassurance. Lasers may be all around us, in CD players and at supermarket checkouts, but some of us are old enough to remember what Auric Goldfinger's laser nearly did to James Bond.

Lidar is another thing entirely. It will not slice you in half.

And it's perfectly safe to look up when Lidar is looking down at you.