What is corroboration?

- Published

Lord Carloway is the only judge to favour the change to corroboration

Scots Law includes a unique requirement that accusations be corroborated. But what does this mean and would its removal help prosecute cases such as rape?

Scotland has its own distinct legal system which includes protections for suspects which differ from those elsewhere in the UK.

One requirement unique to Scots Law is the need for corroboration of the essential facts in the case against the accused.

In other words that there must be two separate sources of evidence before a case can proceed to trial.

It means that the accused cannot be convicted on the word of one person alone with no supporting evidence.

Corroborated evidence does not have to come from forensic science or witness testimony: it can be circumstantial or in certain cases can relate to the previous convictions of the accused.

For prosecutors, corroboration is a particular problem in rape cases, especially where the accused claims that sexual activity was consensual.

Scotland has its own distinct legal system

The debate is hampered by a lack of recent reliable statistics but campaigners from Rape Crisis Scotland have claimed, external that the rate of rape convictions in Scotland was as low as 4.6% in 2009/10.

In 2010 Lord Carloway, now the Lord Justice Clerk, Scotland's second most senior judge, was appointed to lead a wide-ranging review of Scots Law, including corroboration.

Lord Carloway's appointment followed the case of a man who in 2009 successfully appealed against an assault conviction on the grounds that he had been denied access to a lawyer while being interviewed by the police.

This was standard practice: until the Cadder case, suspects could be questioned in Scotland for six hours without a lawyer present.

That has now changed after Mr Cadder won his case in the UK Supreme Court, which ruled that denying a suspect access to a lawyer contravened the European Convention on Human Rights.

The Cadder case led to changes in how long a suspect can be detained without charge

Suspects in Scotland now have a right to a lawyer from the point at which they are "detained" although the time they may be detained without charge has been extended to 12 hours or, in certain cases, 24 hours.

Rape Crisis Scotland claims that Cadder will further push down rape convictions because suspects are now more likely to take the advice of a lawyer and remain silent during police interviews.

Lord Carloway's report recommended, external, among other things, that corroboration be abolished.

As part of his review, research carried out by Scotland's prosecuting authority, the Crown Office, found that between July and December 2010, no criminal proceedings were taken in 141 of the cases involving allegations of serious sexual offences which were reported to the National Sex Crimes Unit.

Prosecutors argued that 95 of those cases could have gone to trial if corroborative evidence had not been needed.

The recommendation to scrap corroboration is supported by the Scottish government, the Crown Office, Police Scotland and campaigners for victims of domestic violence and rape.

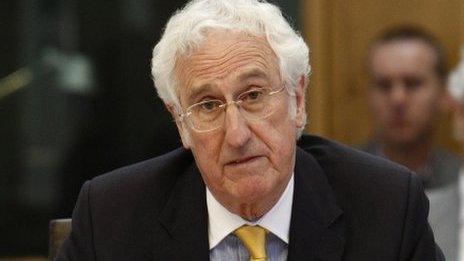

Lord Gill came before members of Holyrood's justice committee

It is opposed by all of Scotland's other high court judges, led by Lord Gill, Scotland's most senior judge.

Making particular reference to rape cases, the judges have warned that "the abolition of corroboration may result in miscarriages of justice".

It is also opposed by many criminal lawyers, external.

Some have even argued that the proportion of rape convictions might fall if corroboration is removed, external because police investigations might be less rigorous.

Nonetheless, the justice secretary in the Scottish Government, Kenny MacAskill, is now pressing ahead with a bill to remove the requirement for corroboration, arguing that, "the rule stems from another age, its usage has become confused and…it can bar prosecutions that would in any other legal system seem entirely appropriate."

The Criminal Justice (Scotland) Bill, external is now before the Scottish Parliament where it is expected to pass the first of three stages - consideration by MSPs on the Justice Committee - at the end of February.

The bill includes a proposal to increase the majority of jury members required to return a verdict from a simple majority to a two-thirds majority.

Billed as a safeguard for the accused, this would mean that a jury with its full complement of 15 members would require at least a 10-5 split for a guilty verdict rather than a minimum of 8-7 at present. Lord Hamilton, who was Scotland's top judge until 2012, has suggested that a split of 12-3 would be safer.

At least one alternative to abolishing corroboration has been suggested: allowing juries to take a suspect's refusal to answer questions into account when considering a verdict.

At present, in Scotland - unlike in England - no inference can be drawn from an accused exercising his right to silence.

For example, if a suspect does not mention during a police interview that he had consensual sex with his accuser but later relies on this as his defence when, say, DNA evidence emerges, then, at present, a jury cannot take this into account.

At present it appears that the Criminal Justice Bill has the necessary support from MSPs to become law. Whether it does or not, the controversy about such fundamental redesign of a centuries-old legal system is unlikely to abate.

- Published7 January 2014

- Published20 November 2013