World War One: Zeppelin raid was Scotland's first air blitz

- Published

The Zeppelins were used to drop bombs during the early years of World War 1

The first air raids on Scotland did not come during the blitz of World War Two, but almost 25 years earlier when German zeppelins bombed Edinburgh during World War One.

The Zeppelin, a motor-driven rigid airship, was developed by German inventor Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin in 1900.

Before the outbreak of WWI it had been used for passenger flights, but from January 1915 the zeppelin was pressed into action for bombing missions against the English coastline, with Great Yarmouth and King's Lynn first to be hit.

The huge lumbering airships would appear to us now as easy targets for anti-aircraft weaponry, but even basic weapons were not available to counter the threat until the following year.

Blackouts and evacuations were of the most basic kind, and despite being warned of the raid hours in advance, there was little people could do except wait for the bombs to be thrown from the airships.

On the evening of Sunday 2 April 1916, two German Zeppelins reached the Firth of Forth and set about conducting the first ever air raid on Scotland.

It is thought the Zeppelins were supposed to meet up with two other airships, but one turned back because of navigation problems and the other appears to have got lost and released its bomb load over fields in Northumberland.

The targets for the two airships which did make it to the Scottish coast were probably the docks at Rosyth and the fleet moored in the Forth.

However, the Zeppelins appear to have turned inland to the city to find new targets.

The first reports of bombs exploding in the Leith direction came shortly before midnight.

Over the next 35 minutes, 24 bombs were dropped on the city of Edinburgh. Thirteen people died and 24 were injured in the attack.

Ian Brown, assistant curator of aviation with the National Museum of Scotland, based at the National Museum of Flight at East Fortune airport in East Lothian, says bombs, both high explosive and incendiary, were dropped across a large area of Edinburgh and Leith.

He says: "The idea was to destroy property and set fire to them and cause civilian casualties. Basically their aim was terror attacks."

One bomb fell on a bonded warehouse at Leith, lighting up the whole city. Several others fell along the shore at Leith, one hitting St Thomas's Parish Manse in Sheriff Brae and another falling on a railway siding at Bonnington, where a child was killed.

An empty patch of land at Bellevue Terrace was hit, smashing windows in the surrounding streets.

The fire brigade reported that the bomb left a cavity measuring 10ft by 6ft.

One of the airships then appeared to aim for Edinburgh Castle.

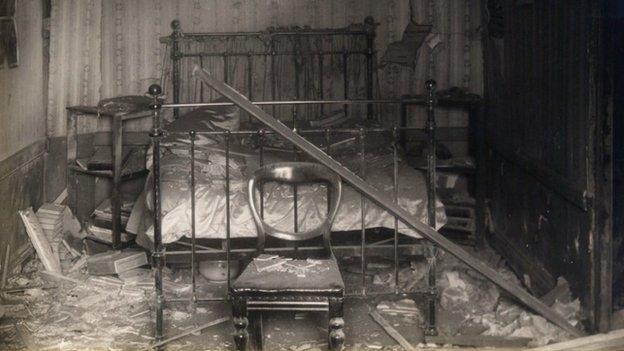

A bomb hit the road by the Mound and another ploughed through the home of Dr John McLaren at 39 Lauriston Place.

The bomb hit the tenement and went through the ceilings and floors of four storeys without injuring anyone.

Hamish McLaren, a retired consultant physician from Stobhill Hospital in Glasgow, is the grandson of the man who owned the house at the time.

He told the BBC that his father, who was just eight in 1916, had been in the house, near Edinburgh Castle.

He says: "I don't know whether they were actually trying to bomb the castle and missed it, or whether they were jettisoning the bombs to get away.

"In the house there was my grandfather and my grandmother, their three children, of which my father was one, and two maids.

"The damage was very extensive.

"The bomb exploded on the roof, blew the roof off, and then the nose of the bomb came down through the four floors of the house and ended up in the pantry."

Mr McLaren says the nose of the bomb was recovered from the basement and is now a family heirloom.

He says: "That's been mounted on a bit of oak, which was apparently from the sideboard that was damaged, and my son has that down in Essex."

Hamish McLaren said his father had written an eye witness account of the raid.

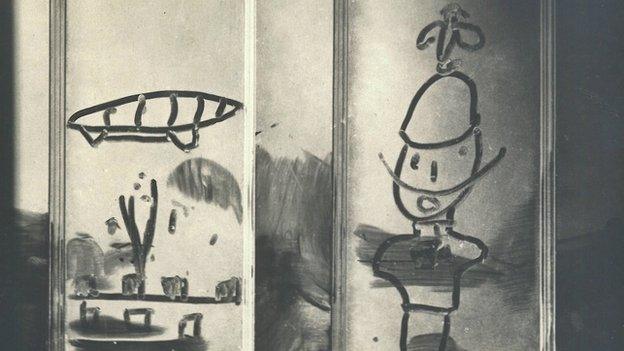

Child's drawing of a Zeppelin in the dust left after the house at Lauriston Place was bombed

The account says: "They heard the bomb, which was a 100lb bomb, coming, and my father said to my mother, 'this has got us'.

"He was right. The bomb exploded on the roof almost mid-way between number 39, us, and 41, the Skins (School for Children with Skin Diseases) school.

"It blew off most of the roof, blew out all the plate-glass windows, and the nose of the bomb, a large lump of steel, continued through all the floors of the house until it reached the pantry where the stone floor stopped it.

"Needless to say I was awakened by this explosion and I was very frightened but did not cry."

Bombs were falling all over the city during this period.

An explosive bomb fell in the grounds of George Watson's College and an incendiary bomb hit the Meadows.

Other bombs hit Edinburgh Castle rock itself, and there is a plaque high up on the rock which commemorates the spot.

Bombs also struck the Grassmarket, in front of the White Hart Hotel, and the County Hotel on Lothian Road.

Six people taking refuge in the entrance of a "working class tenement" in Marshall Street died when a bomb hit the pavement just outside, the police report said.

And a child was killed and two people injured at a tenement on St Leonard's Hill.

A fire brigade report from the time describes a miraculous escape at a house in Marchmont Crescent.

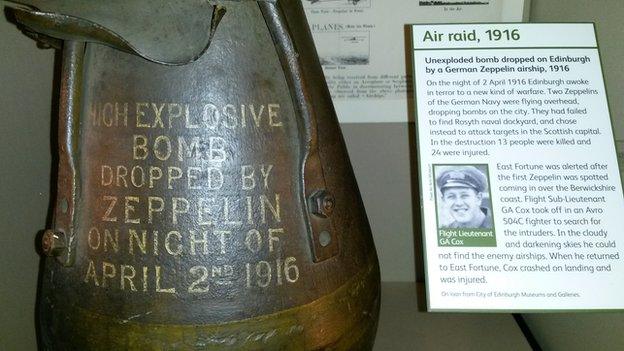

The unexploded bomb dropped by the zeppelin is now on display at the Museum of Flight in East Lothian

It says: "An explosive bomb struck the roof and penetrated to the ground floor, through the lobbies of each floor, wrecking the lobbies. This bomb failed to explode."

Mr Brown, from the Museum of Flight, says it appeared from the police and fire reports of the time there were only two high explosive bombs that failed to explode.

He says: "We have one unexploded high-explosive bomb at the National Museum of Flight on display there, kindly loaned by Edinburgh City Museums.

"From these reports I am fairly certain that the bomb we have on display is the one that landed at 30 Marchmont Crescent."