World War One: The labour camp for peace protesters

- Published

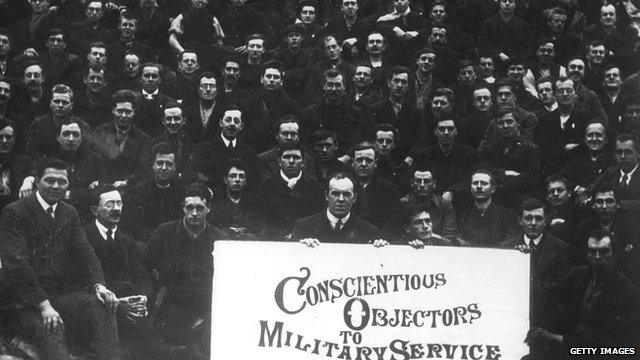

Conscientious objectors face the camera at Dyce Camp, during the worst days of fighting on the Western Front

Some World War One conscientious objectors were sent to work camps. The conditions at one facility in Aberdeenshire saw it closed down months after a young man died from pneumonia.

By the second year of the war, the initial flood of volunteers had slowed to the point where Britain was forced to introduce conscription for the first time in its history.

The Military Service Act, which came into force in March 1916, allowed for objectors to be exempted from service on religious, moral and political grounds, but their appeals were judged by a military tribunal.

Thousands of objectors were sent to do "work of national importance", such as farming, and many more performed non-combat duties, such as working as ambulance men or stretcher-bearers in war zones.

Others were forced into the army, and when they refused orders, they were sent to prison.

There was much public criticism over able men sitting in jail when they could be doing useful labour.

So a project was devised under which the men would break rocks in the north of Scotland for use in road construction.

Some were sent to a camp in Ballachulish in the Highlands. The men faced tough work and poor conditions, but at least they were housed in huts.

Other conchies were sent to the camp at Dyce, situated on a windswept hillside, which is now used as a long-stay car park for Aberdeen airport.

They lived in army surplus tents that leaked in the rain and worked smashing granite in the nearby quarry.

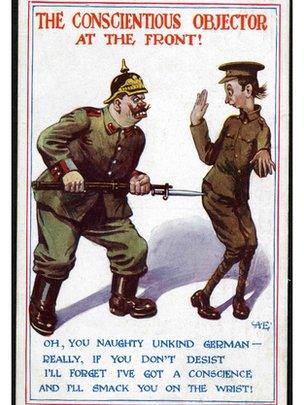

The public attitude was not kind to conscientious objectors

Aberdeen University historian Joyce Walker says about 250 men, most of them sent up from England, were taken to the work camp.

She says: "They were scholars or academics, students, teachers, shopkeepers, labourers, the whole range of human endeavour.

"They were mainly well-educated and articulate men. They had all been in prison and saw this as a means to a slightly better life."

The public mood was not sympathetic to conscientious objectors (COs), with many considering them traitors and cowards whose presence was an insult to the north-east men who had left to fight on the front.

Local newspaper the Aberdeen Journal wrote a virulent editorial attack on them in September 1916, soon after the camp opened.

Living conditions

It said: "A conscientious objector in war-time is a degenerate or worse, who is out of harmony with the people of the nation which protects him in peace-time and defends him in war-time.

"The No-Conscription Fellowship, which champions these shirkers of their duty, is under so deep a cloud of suspicion that no fewer than 27 raids by the police have been made, within the past week, or so on the houses of secretaries and members in the London area."

According to Ms Walker, the living conditions for COs at the Dyce camp were extremely poor.

She says: "They were in army surplus tents and the story goes that the surplus was from the Boer war. So they were old and very leaky tents.

"The men slept on straw paliases (mattresses) on the ground and they were not permitted to build up with stones or wood to get off the bare ground.

"So it was very cold and when it was wet, they were on a hill, so the water just ran straight down through their tents."

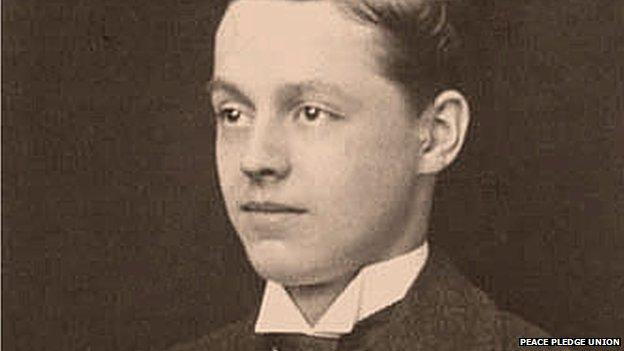

Walter Roberts was a committed Christian and pacifist who objected to military service

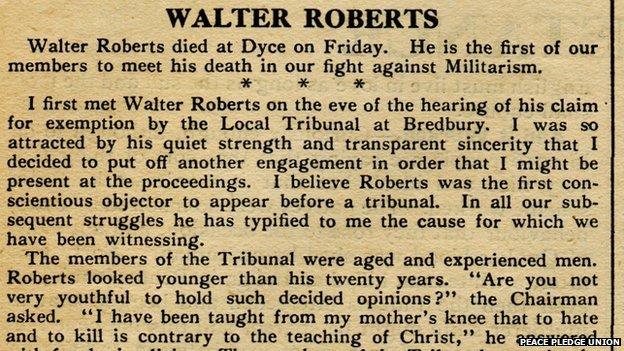

One of the men in the camp was 20-year-old Walter Roberts, from Bredbury near Stockport, who had refused military service saying he was a Christian who had always renounced violence.

Roberts had already been weakened by months in prison when he was sent to the camp. He died from pneumonia on 8 September, five days after his arrival.

Two days before his death he wrote to his mother saying: "As I anticipated, it has only been a matter of time for the camp conditions to get the better of me. Bartle Wild is now writing to my dictation because I am now too weak to handle a pen myself.

"I don't want you to worry yourself because the doctor says I have only got a severe chill but it has reduced me very much.

"All these fellows here are exceedingly kind and are looking after me like bricks so there is no reason why I should not be strong in a day of two when I will write more personally and more fully."

Ms Walker says the death of Walter Roberts upset the rest of the camp and they wrote to the authorities to complain about the conditions.

A Home Office delegation, including some MPs, was rapidly dispatched to Dyce and shown around the camp by the inmates.

Walter Roberts's obituary in the Tribunal newspaper, which supported the peace campaigners

Ms Walker says: "Their opinion was that the camp was OK as long as efforts were made to move the men from the tents into barns and lofts and outhouses and disused Cotter houses, anything that was dry or drier than the tented village."

She adds: "Coincidentally, or perhaps not, on the same day, Ramsay Macdonald, the Labour MP, was on his way south after being on holiday.

"He stopped off and came up to the camp to have a look for himself.

"Of course, he was much more sympathetic to the conscientious objectors than most were and his view of the camp was very different to that of the Home Office delegation. He thought it was shocking."

Ms Walker adds: "A month later, on 19 October, there was a big debate in parliament about it and at the end of the debate the chairman of the Home Office committee that had come up, a chap called William Brace MP, announced suddenly that the camp was closing.

"They had decided it would cost too much to make the necessary adjustments, repairs, and arrangements and it would close. The camp closed at the end of October."